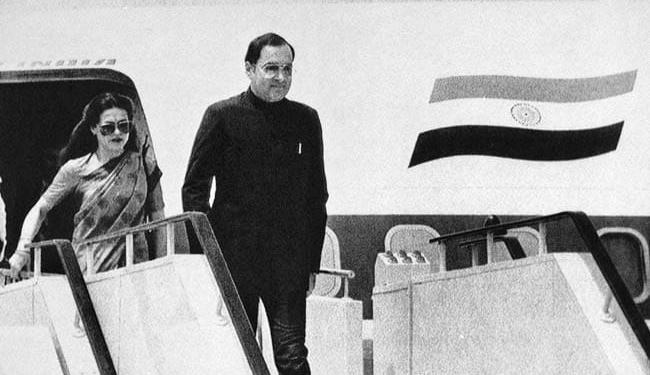

Rajiv Gandhi, the erstwhile Prime Minister, son of Indira Gandhi and father of Rahul Gandhi, has been termed as “corrupt number 1” in the heat of the elections. Many a Congress members including P Chidambaram and Ahmed Patel, are expressing outrage over this, claiming that “Rajiv Gandhi was given a clean chit by the Delhi High Court for his involvement in the Bofors scandal.” However, the man has quite a few skeletons in his closet which are being exposed as the citizens are digging deeper into his sordid legacy. Rajiv Gandhi’s involvement in securing commercial aircraft for Air India (previously known as Indian Airlines) during his tenure as well as his mothers’ is one of the little known sagas of irregularities.

A Business Standard investigation revealed quite a few interesting developments during the years 1976-77 when Boeing aircraft were being purchased for Indian Airlines. According to Justice J C Shah Commission, which probed the excesses during the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi’s interference in the procedure to procure three Boeing 737 aircraft, amounting to a total cost of RS 30.55 crore; amply clear.

To choose between the three options of Boeing, F-27 and British Aircraft Corporation’s BAC111 (the two competitors of Boeing had already completed route testing); an Interline Committee was supposed to go into the details and study the proposals. However, even before the committee could come up with its findings, a meeting took place in the office of A H Mehta, the then acting chairman of IA, where Rajiv Gandhi was present along with Kirpal Chand, IA’s director (Finance), and A M Kapoor, IA’s director (Operations) where he was shown the financial projections. During the meeting, AM Kapoor had also stated that “he did not understand why there was so much delay in the progress of the case dealing with the purchase of the Boeing aircraft, which… were operational and technically superior.”

One of the first things the Shah commission did was to point out that “the visit of Rajiv Gandhi to the office of the chairman of Indian Airlines where he was shown the financial projections by the director of finance, apparently under the instructions of the chairman, was a procedure which was totally outside the ordinary course of business.”

Apart from the undue influence in the procurement process, witnesses suggest the deal was under immense political pressure. N K Mukarji, the then civil aviation secretary, had received a call from P N Dhar, secretary to the Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi. First, Mukarji was told that it was the “prime minister’s impression that the tourism and civil aviation ministry was obstructing the purchase of Boeing 737 aircraft by Indian Airlines.”

Thereafter, when he informed that there was an interline committee constituted to look into the matter, Mukarji received a call from R K Dhawan, then additional private secretary to the prime minister, during the time he was in the meeting to discuss the matter and was heard saying: “Yes, Dhawan sahib, I am going into the matter with my officers, who are with me.”

Then on, according to Mukarji, efforts were made to “haste(n) in rushing through the deal.” A letter of intent was issued by the IA management and within a month the IA board had approved the selection and sought the government’s approval to purchase the aircraft. Thereafter, at the meetings of the Public Investment Board (PIB) it was decided that a system study should be undertaken and completed by IA on the suitability of Boeing 737 aircraft.

At this time, the Raghuramaiah had been newly appointed as the civil aviation & tourism minister in Indira Gandhi’s cabinet. He had admitted to having been directed by Dhawan to look into the matter urgently and stated that what emanated from Dhawan was taken as “emanating from the prime minister.” He went on to add that as minister in-charge of parliamentary affairs in his earlier role, he had “obtained the resignations of Raj Bahadur (the previous the Civil Aviation & Tourism minister) because Dhawan had told him to do so.”

Thereafter, the decision to purchase the Boeing 737 aircraft had been taken without the mandatory “system study” and an order was placed subsequently after the Cabinet overruled objections raised by the PIB.

All in all, the Shah commission concluded that the procedure for procurement of the three Boeing aircraft broke all standard rules and requirements. However, the commission’s findings were completely futile as Indira Gandhi returned to power in January 1980, and thereafter no trials against the perpetrators were conducted.

As if one such incident of such grave undue influence wasn’t enough, Rajiv Gandhi once again interfered in the procurement of the next set of aircraft. The investigation into the crashing of Indian Airlines A320 Airbus in 1990 gave insights into Rajiv Gandhi government’s undue haste in pushing the A320 Airbus deal after brushing aside the need for more time to evaluate the aircraft.

In 1983, when the need for the aircraft arose, Boeing aircraft was being considered, since it was a tried and tested aircraft already being used in the fleet. So much so, that a letter of intent had been issued along with an advance of Rs 1.35 crore for the procurement of the aircraft with the promise of a firm order being placed soon. However, Rajiv Gandhi formed the government in 1984 and after showing an unusual amount of interest at the Paris air show, started focusing on Airbus Industrie to sell the A 320 Airbus.

Thereafter, the government sought to hasten the procedure to obtain the aircraft after bypassing all the procedures. They completely ignored the proposal from Boeing offering their aircraft at a negotiable price and placed the order for the A 320 Airbus.

An official in the Ministry of Finance stated, “I am constrained to observe that… (the Boeing purchase) has not been pursued by Indian Airlines with the requisite diligence and urgency.” The deal wasn’t properly evaluated even though no other country had placed orders for the Airbus 320 anywhere near to the size of the Indian deal.

Moreover, the Indian Airlines had resorted to lie to a query of the Ministry of Civil Aviation in order to ensure smooth procedure of the deal, when the managing director Kamini Chadha had stated that the aircraft would not require any additional expenditure on the infrastructure. However, the government incurred an additional expenditure of Rs 250 crore for providing facilitates and training for the use of the engine.

The Government had ordered two batches; of 19 aircraft in 1985 and an additional order for 12 aircraft in 1988, both approved with lightning-speed by the ministry and the Union Cabinet. On this decision, the planning commission had categorically stated that the additional requirement was only of 4 aircraft and not of 12. Moreover, it was suggested that the government should explore other competitors or at the very least evaluate the performance of the 1st batch before placing the order. But the advice wasn’t paid any heed to.

However, the most baffling part of the purchase was Indian Airlines’ refusal to wait for a detailed investigation of the crash of the Airbus 320 at the Paris air show in 1988; neither did they evaluate the V-2500 engine with which the aircraft was to be equipped. It is pertinent to note that the Airbus offer had become cheaper than Boeing’s only after this engine was selected as part of the package negotiated.

It wasn’t just the planning commission or the Ministry of aviation or the Ministry of Finance which were skeptical. In October 1988, the Indian Commercial Pilots’ Association wrote in a letter to the Government: “We state that the aircraft is neither proven nor does Indian Airlines have the infrastructure to maintain them….Even a freak chance of main and backup computer failure due to dust, heat, or humidity will end in a disaster as the pilot shall have no control whatsoever…”

However, it was clear from the way Indian Airlines and the government was handling the process of purchasing the additional aircraft that it had foreclosed all other options. The government had disregarded all safety precautions and proceeded with the order without waiting for an investigative report on the air crash or an evaluation of the engine. It is strange to note that even after a number of objections, doubts and misgivings over the performance of the aircraft, the order had been placed, that too in a very hasty manner. The government, while negotiating the deal had disregarded their requirements on the suitability of the Airbus in India, the number of airbuses needed, the performance and the track record of the engine and even the procedure of the deal. It makes one ponder upon the sense of urgency prevailing in Rajiv Gandhi’s government to conclude the deal.