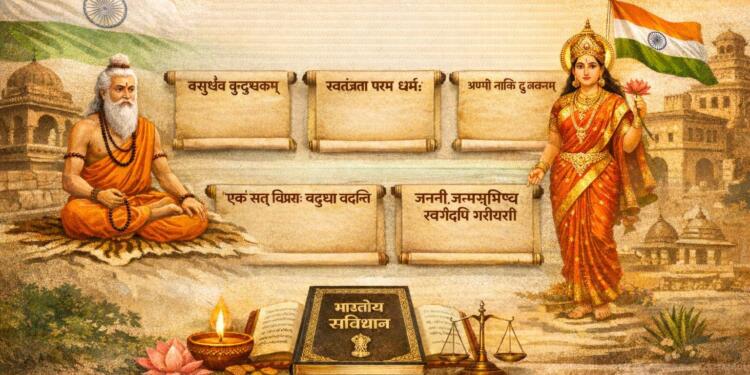

The Indian Constitution carries a profound imprint of the Indian knowledge tradition. In this Constitution Series, Fundamental Rights are interpreted through the moral framework of Sanatan Darshan.

Fundamental Rights constitute one of the most significant pillars of the Indian Constitution. Their primary purpose is to ensure that every citizen can live a life of dignity. These rights are not merely legal guarantees, they are a living expression of the citizen’s entitlement to dignity, their moral duties, and their civic responsibility toward the nation.

Enshrined in Part III of the Constitution (Articles 12 to 35), Fundamental Rights presently number six. The Right to Property was removed from this category by the 44th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1978 and was reclassified as a legal right.

The six Fundamental Rights include the Right to Equality, the Right to Freedom, the Right against Exploitation, the Right to Freedom of Religion, Cultural and Educational Rights, and the Right to Constitutional Remedies—described by Dr BR Ambedkar as the soul of the Constitution.

It is often argued that these rights were borrowed from Western constitutions such as those of the United States, Britain, Ireland, and France. However, such an interpretation overlooks India’s own intellectual heritage.

A deeper examination of Indian philosophy and the Indian knowledge tradition reveals that the principles underlying Fundamental Rights were deeply rooted in Indian society long before modern constitutionalism. The Constitution, therefore, represents not an import but a constitutional rearticulation of India’s civilizational wisdom.

Right to Equality (Articles 14–18)

The Right to Equality encompasses equality before law, prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, caste, and gender, and equality of opportunity in public employment. In the Indian knowledge tradition, equality is not confined to legal formalism; it is grounded in profound philosophical and ethical principles.

Upanishadic concepts such as “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” and “Eko’ham Bahusyam” express the idea that all beings arise from a single universal consciousness. From this perspective, equal treatment of all is an essential expression of dharma. The Mahabharata states, “Dharmena heenah pashubhih samanah”, emphasizing that justice and moral equality distinguish human society from brute existence.

Ancient legal and political traditions, as reflected in the works of Manu, Yajnavalkya, and Kautilya, instruct the ruler to administer justice impartially, without distinction between friend and enemy, kin and stranger. In the Shanti Parva, the king is urged to be “Samadarshi in all beings”—one who perceives all with equal regard.

The rejection of social hierarchy based on birth finds even stronger articulation in Buddhist and Jain traditions. Buddha explicitly denied caste superiority and upheld conduct and action as the true measure of a person. Jain philosophy similarly stresses equality and non-violence (Ahimsa) toward all living beings.

The idea of equal opportunity is further reinforced by the doctrine of karma in the Bhagavad Gita. “Karmanyeva adhikaraste” affirms that every individual possesses an equal right to progress through action. The constitutional Right to Equality thus emerges as the modern legal embodiment of an eternal Indian vision—one in which equality is both a right and the foundation of a dharma-based social order.

Right to Freedom (Articles 19–22)

The Right to Freedom includes freedom of speech and expression, association, movement, residence, profession, protection of life and personal liberty, and the right to education. Within the Indian knowledge tradition, freedom is not understood as unrestrained license but as liberty guided by self-discipline, reason, and dharma.

The Upanishadic vision of spiritual liberation and the Gita’s doctrine of Karma Yoga emphasize that true freedom arises from responsibility and ethical action. The roots of freedom of expression can be traced to India’s long tradition of intellectual dialogue. Upanishadic debates, Shastrarthas, and Buddhist assemblies demonstrate that free inquiry and discussion were integral to the pursuit of truth.

The Rigvedic invocation “Aa no bhadraah kratavo yantu vishwatah” reflects an openness to noble ideas from all directions. Freedom of association and peaceful assembly finds resonance in the functioning of Buddhist Sanghas, Jain Sanghas, and ancient republican systems such as Vaishali, where collective decision-making and civic participation flourished.

Freedom of movement, residence, and profession mirrors the openness of India’s socio-economic life. In the Arthashastra, Kautilya assigns the state the responsibility of protecting trade, labour, and livelihoods to ensure social stability and individual self-reliance.

The sanctity of life and personal liberty occupies a central place in Indian thought. Principles such as “Ahimsa Paramo Dharma” and “Jeevet Sharadah Shatam” affirm the sacredness and dignity of life. The duty of the state to protect life, honour, and liberty finds its modern constitutional expression in Article 21.

Accordingly, the Right to Freedom in the Constitution reflects the Indian ideal of disciplined liberty—freedom harmonized with duty and social responsibility. To prevent liberty from descending into arbitrariness, the Constitution provides for reasonable restrictions. This balance is consistent with the spirit of the Isha Upanishad’s injunction: “Tena tyaktena bhunjitha, ma gridhah kasya sviddhanam”, which emphasizes restraint alongside enjoyment.

Right against Exploitation (Articles 23–24)

The Right against Exploitation prohibits human trafficking, forced labour, and child labour for children below the age of fourteen. In the Indian knowledge tradition, exploitation is unequivocally regarded as adharma.

The Vedas, Upanishads, Smritis, and epics consistently affirm human dignity, the sanctity of labour, and individual freedom. The Rigvedic sentiment “Ma himsyat sarva bhutani” and the ideal of “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” morally repudiate all forms of exploitation.

The constitutional rejection of trafficking and bonded labour aligns with the traditional Indian understanding of service as voluntary, dignified, and humane. Texts such as the Manusmriti and the Arthashastra assign the state a clear duty to protect workers, ensure fair remuneration, and prevent inhuman treatment. Kautilya explicitly condemned forced labour and unjust bondage as punishable offences, affirming that human beings are bearers of dignity, not objects of exploitation.

The prohibition of child labour is closely connected to the concept of Brahmacharya Ashrama, which regards education, moral formation, and character-building as the primary responsibilities of childhood. The Guru–Shishya tradition reinforces the view that childhood must be protected and nurtured as a vital social trust.

Thus, the constitutional Right against Exploitation represents the modern legal continuation of the Indian knowledge tradition’s commitment to ahimsa, compassion, justice, and human dignity, providing both ethical and constitutional safeguards against all forms of inhuman exploitation.

Dr Alok Kumar Dwivedi holds a PhD in Philosophy from Allahabad University. He is currently working as an Assistant Professor at KSAS, Lucknow. This institution is the India-based research center of INADS, USA. Dr. Alok’s academic interests include philosophy, culture, society, and politics.