In the last chapter of the series, we saw how the confrontation between Islam and Byzantines shaped the world’s geography. While Christians were fighting to get back Jerusalem, they had split into two halves in 1054 AD; Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Clearly, the unifying theme was disappearing and the Pope was becoming a powerful authority. 41 years later, it was a Pope who ultimately authorised the first Crusade.

The conflict between Muslims and Christians in 11th century

However, its base was set decades before it even started. The ‘Papacy’ (authority of the Pope) was supposed to be a pacifying authority. To be fair to them, they did play their part by trying to mitigate regional conflicts between warrior castes of the deracinated Carolingian Empire. However, the fact that Jerusalem was not under their control and the rise of Seljuk Turks became the main reasons for the Church to vindicate military actions.

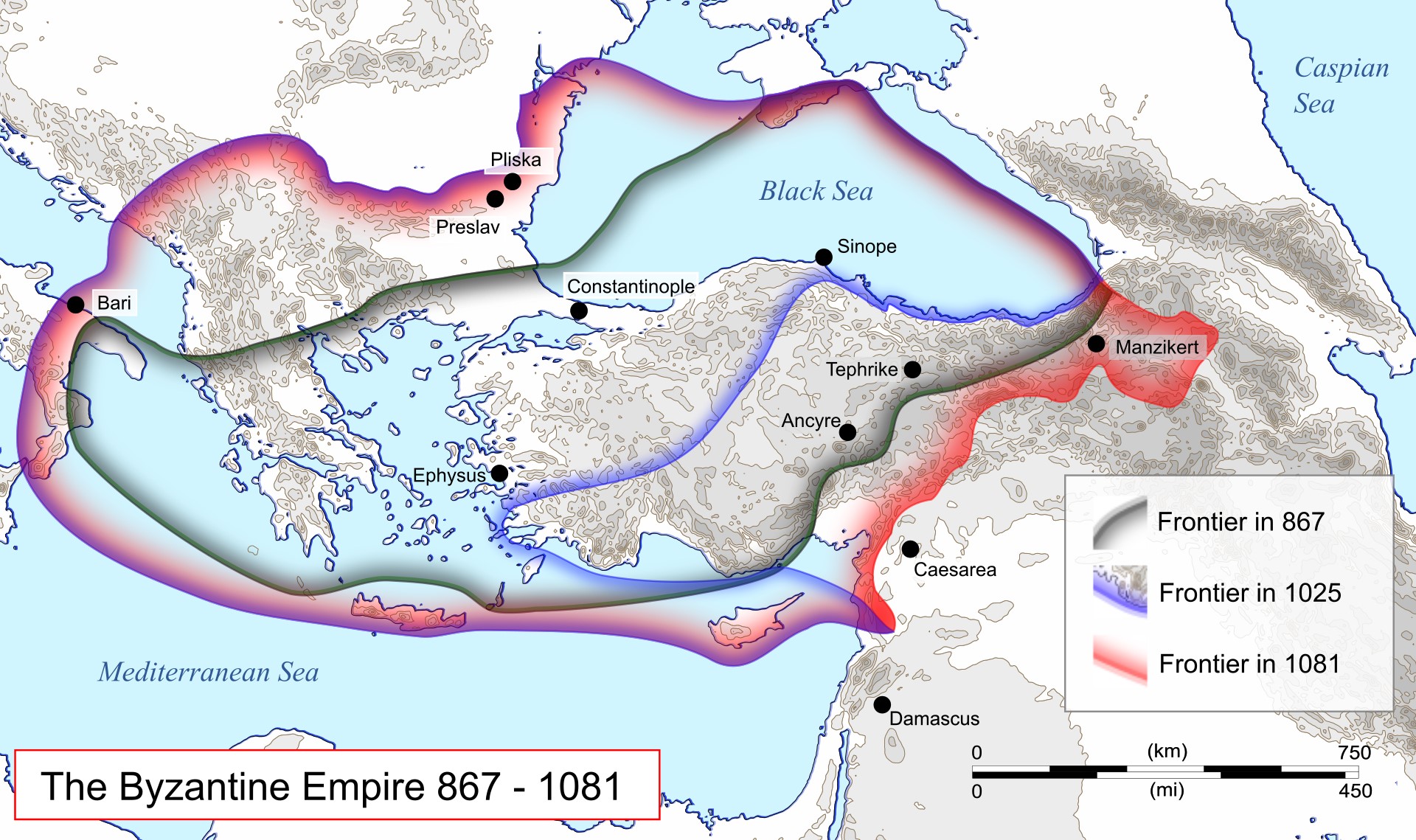

Seljuk Turks originally belonged to Central Asia and had recently converted to the Sunni sect. In the 11th century, they had occupied greater territory than Arabian Muslims. When they proceeded towards the Byzantine Empire, Romanos IV Diogenes did try to stop them. Unfortunately, in 1071 AD, he became the only Byzantine emperor to ever become a prisoner of Muslims after a crushing defeat in the Battle of Manzikert. Seljuks proceeded to capture Anatolia, Nicaea and Antioch, the major heartlands of the Byzantine Empire. This is how the Byzantine Empire looked after the fall of Nicea in 1081 AD.

In the same year, Alexios I Komnenos came to power in the Byzantine Empire. He later went on to play a key role in the Crusades.

Build-up to Crusades

While Christian rulers were busy fighting Islamic invaders, the Papacy was gradually building an army of its own. It was started by Pope Alexander II and later given an edge by Pope Gregory VII, his successor. Pope Gregory even went on to plan a display of military power but did not have much theological support. It was provided by Anselm of Lucca who floated the idea of remission of sins through holy war against Muslims. Initially, these fighters were deployed in the war against Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula. Apart from that, Papacy’s role was limited to regional conflicts.

Things changed after 1092 AD when Seljuk Turks themselves fragmented into separate warlords after the death of Sultan Malik Shah in 1092 AD. These warlords were hell-bent on expanding to the leftover territories of the Byzantine Empire. Alexios I was not liking it, but he did not have many resources to allocate at varying war zones. He needed more and thought of consulting Papacy for that.

Alexios I wrote to Pope Urban II for a military aid. Pope Urban sensed an oppotunity to undo the schism and assert Papal authority on both schisms. He started preaching at Clermont, France, asking locals to head towards the East. He told them to free Jerusalem and in return, they were offered to substitute this mission for penance. In other words, if a Christian participated in the war against Muslims, he could offset it with all of his sins.

Jerusalem unified Christians

At that time, Europeans were extremely divided tribes with a lot of infighting among them. Jerusalem being a holy city was the only thing that could unify them and direct their violence in a relatively sacred direction. Pope Urban had imagined that these violent rebels would be led by elite military heads and other nobles. But he would never have imagined the virality of his sermons.

His words quickly reverberated all across western Europe and common folks were more ready than knights to join this supposedly spiritually salivating journey. Thousands of men took the cross (the symbol of the holy journey) and started walking East. These financially poor and spiritually rich people were being led by ‘Peter The Hermit’. He and his followers were the first to respond.

The first offence ended in failure

At the end of the day, Peter was a priest and it was always going to be tough for him to maintain military discipline among his untrained warriors. When they proceeded towards Jerusalem, these people were often repelled by local Christians en route. The main reason behind it was their unruly behaviour and troubling locals.

In Rhineland, they committed a historically significant massacre of innocent Jews. It did not matter that massacre did not have any approval from the Church whatsoever. In Hungry, they did the same with Christians and looted their resources to satisfy their hunger. Even Alexios was fed up with them, and that is why, when they reached Constantinople, he was quick to ferry them off to Anatolia, the Islamic territory. It is there that they got the test of reality when Seljuk Kilij Arslan thrashed them at the Battle of Civetot in October 1096 AD. These people did not even wait for their disciplined brethren to arrive and ultimately succumbed to Seljuks.

Well organised offense by well organised Army

Their more hostile and more disciplined force consisted of Godfrey of Bouillon and his brother Baldwin of Boulogne, Italo-Norman forces led by Bohemond of Taranto and his nephew Tancred, northern French and Flemish forces under Robert Curthose (Robert II of Normandy), Stephen of Blois, Hugh of Vermandois, and Robert II of Flanders. All of them combined are believed to have 1 lakh men under their command. Every faction had its separate routes and ultimately joined hands at Constantinople.

It is here that the first internal conflict came to the forefront. Byzantine Emperor Alexios had thought to lead a small contingent but was shell shocked to find his enemy Bohemond of Taranto. Bohemond had spent his life attacking the Byzantine Empire. Alexios gave them food, money and other resources only on the promise that his share of the Empire would be returned to him.

Differences did not weaken morale

The Byzantine forces became part of the crusaders’ Army but somehow maintained their identity. It was visible in the Siege of Nicaea in June 1097 AD. As Islamic forces lost the territory, they surrendered to Byzantine forces, rather than the whole Army. The next stop en route was the city of Dorylaeum.

It is here that the disciplined section of Crusaders tasted its first setback. A contingent of Bohemon was cornered by Turkish Forces and was on the verge of getting annihilated. Fortunately, the unity of Crusaders changed the course of the war as others arrived at the right place and the right time to reverse the gains made by the Turks. Forces of Khilji Arsenal (Seljuq Sultan) fled the war zone.

Despite the last-minute victory, the Crusaders did not lose the momentum and went on to conquer Heraclea on September 15. Within days of the victory of Heraclea, Baldwin of Boulogne and Tancred got greedy and went on to capture more lands for their selfish purpose. Tancred did come back to join the Crusaders but Baldwin was more interested in becoming the ruler of the 1st crusader state. On the invitation of Armenian Christians, he went to Edessa and soon became Count Baldwin of Edessa.

The moment when Turks realised the enormity of the problem

In October, crusaders arrived at the gate of Antioch. It was the final frontier before Jerusalem, but the issue was that it was the strongest hold of Seljuqs. Here they faced a big problem of supply and other stuff. Hunger death became common among crusaders and it is said that outside Antioch, Crusaders had to rely on their dead horses’ blood for liquid. It continued for around 5 months until a reinforcement ship arrived with men and supplies from Cyprus.

With renewed energy, they found a way to break into the city as well. Islamic commanders of Antioch were bribed and one fine day, Bohemond of Taranto attacked a tower with merely 60 men and succeeded. The Crusaders got a much-needed break and after that, it became a cakewalk for them. The desperation to seize the city can be gauged from the fact that supposedly, the Crusaders did not differentiate between citizens and military while slaughtering them. Antioch was finally done and dusted.

At this point, Turks felt for the very first time that it was not just a military campaign. The Christian zeal for the holy land was real and the only way for the Turks to counter them was coming together. Kerbogha, the Governor of Mosul assembled a giant Turkish Army and launched a methodical offence on Crusaders. He first took control of Edessa, but let it go after 3 weeks. Then he headed towards Antioch.

Holy Lance acted as a morale booster

In Antioch, Crusaders were lying exhausted with no expectation of relief from the Byzantines as Alexios was busy securing his gains.

However, the morale to recapture Jerusalem was renewed by the news of the discovery of the ‘Holy Lance’. It was the same lance that was thrust into Christ’s side at his crucifixion. The Crusaders made a miraculous recovery and charged towards Kerbogha’s army. It is believed that Kerbogha’s Generals had been bribed into submission and as soon as he sensed it, Kerbhuga burned down his military camp. Antioch was well defended. Now, only Jerusalem remained.

But the Crusaders did not have to fight with the Turks to get Jerusalem. Instead, just after the Kerbhuga’s loss, Egyptian Fatimids captured Jerusalem from the Turks.

Problems before the final frontier

Their problems were exacerbated by impending heat and a lack of troops, supplies and time. Fatimids could attack them anytime and they did not have much manpower (only 12,000 were left) or energy to carry out an attack.

Add to that, the division among Crusaders themselves. Stephen of Blois and Hugh of Vermandois had returned. On the other hand, Bohemond of Taranto had made Alexios’ wildest dream come true. He had claimed Antioch to be his own territory, rather than returning it to the Alexiosis of the Byzantine Empire. There were chances of infighting among crusaders, but somehow thousands of average crusaders kept mounting pressure for the final offensive. It helped the leaders keep aside their differences.

Also Read: What made Christianity what it is today, Chapter 2: Crossing paths with Islam

Siege of Jerusalem

In the first trimester of 1099, the final push began. The Crusaders’ offence was welcomed by local Fatimid rulers with money, bribes and men. It was quite a puzzle to begin with, but soon they discovered the reasons behind it. When the Crusaders reached Jerusalem, every natural resource like water and trees was rendered useless for them. The Crusaders were getting jittery, but the leaders wanted to test the waters. They did not have much timber to build siege engines. Despite that on 13th June, they launched their first attack and expectedly were forced to return by Egyptians. On 17th June, Genoese mariners under Guglielmo Embriaco provided the much needed timber to the Crusaders.

With these timbers, they built two siege towers. One was being looked after by Raymond of Toulouse in the southwest while the other was with Godfrey of Bouillon in the north. Godfrey moved his siege tower to the less secure section of the north and launched a massive onslaught on 15th July 1099 AD. The Crusaders killed everyone even remotely dissociated from Christianity. Within hours, the Fatimid governor, Iftikhar al-Dalwa was looking for a safe passage and penned a deal with Raymond for that.

Despite Raymond playing decisive role in the final push, Godfrey of Bouillon was handed over the task to defend the siege. He was given the title of Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri (Defender of the Holy Sepulchre). Unfortunately, Pope Urban II was not alive to see his dream come true.

Support TFI:

Support us to strengthen the ‘Right’ ideology of cultural nationalism by purchasing the best quality garments from TFI-STORE.COM