The issue of religious conversion is a constant and a prominent issue in the political discourse of the nation. For the sake of discussion in this article, I have clubbed the followers of all Indic religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and Native animism) together. Evidently, they are in a massive majority. Modern India, born in the aftermath of partition was designed in a way to serve as a homeland for the followers of Indic religions. No doubt, large numbers of Muslims and Christians chose to stay back in the country (as did many Parsees and Jews). Given that Indian society, shaped by millennia of cultural and religious infusion, is very inclusive, it was obvious that the framers of our constitution bestowed the right to Freedom of religion to all Indians. As early as in 2BCE, Emperor Kharvela had declared “सव पासंड पूजको सवदेवायतन संकार कारको ” (I am worshipper of all sects, restorer of all shrines). And this essentially forms the basis of modern Indian outlook on religion.

The term conversion is not new to India. Asoka accepted Diksha in the aftermath of Kalinga massacre and became a Buddhist. He and many other kings that followed him actively encouraged setting up of Buddhist Sanghas. Upon the rise of Sikhism, Hindu families, it is believed, made their eldest son a Sikh. In the millennia long history of India, there are countless cases of people converting from Hinduism to other religions and vice versa. And yet, conversion of a Hindu to Buddhism or Sikhism or Jainism hardly ever makes news. In fact, other than outward appearance, there is hardly anything that distinguishes the adherents of various Indic religions from each other. Indic religions sprouted in India, they share the same cultural roots, they have very similar notions of right and wrong, their heroes are frequently common as are their enemies ,their outlook on life and death is essentially the same, they celebrate the same festivals, eat similar food and have a great deal of similarity in their rituals. There are obviously some stark differences, but probably they are attributable to a process of divergence that has spawned several centuries.

The entire issue of conversion is linked to conversion of adherents of Indic religions to Islam and Christianity (Judaism does not encourage active proselytizing and Parsees are extremely particular about who is a Parsee). The fact is that native populations of adherents of Islam and Christianity in India have existed ever since the birth of these religions. Now, given that conversion in general is not an issue in India, it is surprising why conversion to Islam and Christianity arouses strong passions.

The first reason for this stems from a sense of historical wrong. There are ample examples in Indian history that show that conversion was undertaken more as an imperialist rather than a spiritual exercise. For example, the conversion of Hindus in Goa was accomplished by the Portuguese soldiers hurling beef at the natives in their villages. These natives lost their caste and were ostracized by their former co-religionists, leading them to accept the Catholic faith. (Similar havoc was unleashed by the Portuguese against the Syriac Christians in Kerala, but that is another matter). There is an entire history of temples being razed, people being forbidden to worship their deities, religious books being burnt and so on. In fact, during the height of Goa Inquisition, natives (even those who had converted to Catholicism) were forbidden from native practices such as planting Tulsi plant in their courtyard, saying namaste, wearing a ponytail etc. Similarly, much of Islamic conversion in India, at least initially, was done with the sword. Muslim Kings prided themselves on their Ghazi status which was attained by butchering a Kaffir. In the aftermath of many battles, the vanquished were given the choice of conversion or death. Evidently, the local populace bristled with rage at having to submit to foreign powers. Understandably, the pages of history are replete with examples, where “their” heroes are the villains of natives. Thus, in many cases, conversion became synonymous with Imperialist aggression against the Natives.

The second reason is that unlike Indic religions, Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Islam and Christianity) are not local. They originated in the Middle East and eventually spread the world over. Their traditions, their folklore, their culture stems from that part of the world. What is holy and godly in India is not necessarily the case in Middle East. Vice versa holds true too. Hence, culturally Indic religions and Abrahamic religions are very different. For instance, perhaps they cannot fathom India’s preoccupation with cows and we probably cannot fathom their fondness for beef. Ganga might be a holy river in India for many reasons, but to many adherents of Abrahamic religions, it is just another river. A convert to Islam or Christianity does not merely change religions, he changes his way of life completely, which in many ways can be completely antagonistic to that of his neighbours and friends. This cultural gulf is another reason for the antipathy to conversion to these religions. Additionally, since the loyalties of adherents of Abrahamic religions lies elsewhere and not necessarily in India (for example the Muslim rulers of yore claimed to rule in the name of the Caliph, or the Portuguese, who ruled with the Pope’s authority), many suspect their fidelity to India (or to put it more dramatically, Bharat Mata).

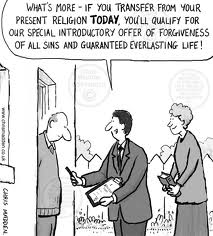

Obviously, there is merit in believing that many conversions to Islam or Christianity took place due to the good deeds of Sufis/Peer Babas/Missionaries. But all that goodness still cannot change the past. Coming back to the pertinent question, Should conversions be outlawed? That perhaps is still a question difficult to answer. What is certain though is conversion under coercion must be banned. Economic inducements also cannot be the reason for conversion. We have to move past the era when a bag of rice was sufficient inducement for a native to change his religion. Clearly, voluntary spiritual grounds alone should justify the reason for conversion, in such a case, whether the conversion is from or to an Indic religion, must be of concern to none. And for the sake of God (of all religions), the issue of conversion must be dealt with maturely, and not as another “breaking news”.

Freedom of religion, as with all other freedoms, needs to be tempered with a sense of responsibility and duty to the nation.