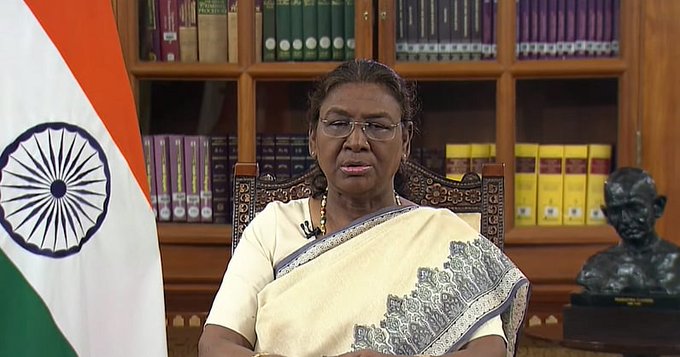

The President of India, Droupadi Murmu, has rejected the mercy petition of a death row convict found guilty of kidnapping, raping and murdering a two year old girl in Maharashtra. This decision, taken on November 6, 2025, closes one of the final legal doors for the child rapist and paves the way for the execution of the sentence awarded to him by the courts.

This is the third mercy petition that President Murmu has rejected since she assumed office on July 25, 2022. Her decision signals a firm stance against extreme crimes of sexual violence, especially those committed against children, where courts have already applied the “rarest of rare” doctrine to award the death penalty.

The case relates to convict Ravi Ashok Ghumare, whose crime shocked the conscience of the nation. The horrific incident took place on March 6, 2012, in the Indiranagar locality of Jalna city in Maharashtra. According to the prosecution, the child rapist Ghumare lured the two year old victim with a chocolate, kidnapped her and then subjected her to brutal sexual assault for hours before killing her.

The trial court examined the evidence and found child rapist Ghumare guilty of kidnapping, raping and murdering the toddler. On September 16, 2015, the trial court awarded him the death penalty, holding that the brutality of the crime and the vulnerability of the victim left no room for a lighter sentence. The court stressed that the act was not only criminal but also a deep betrayal of basic human values and social trust.

In January 2016, the Bombay High Court upheld the trial court’s decision. The High Court agreed that the case fell within the category of the “rarest of rare,” where the death penalty was warranted to reflect the gravity of the offence and its impact on society. With the High Court’s confirmation, the matter moved to the Supreme Court, the final judicial authority in the country.

On October 3, 2019, the Supreme Court affirmed the death sentence in a detailed and strongly worded judgment. A three judge bench, led by Justice Surya Kant, who is now the Chief Justice of India, delivered a 2:1 majority verdict. The court observed that child rapist Ghumare had no control over his “carnal desires” and had crossed all natural, social and legal boundaries merely to satisfy his sexual hunger.

Justice Surya Kant, writing for himself and Justice Rohinton Fali Nariman, described the crime as one of chilling depravity. The judges noted that the victim was a barely two year old baby, kidnapped and then apparently assaulted continuously for four to five hours until she breathed her last. In their words, the convict had “ruthlessly finished a life which was yet to bloom”, turning an innocent child into a victim of his lust.

The majority judgment also underlined the depth of moral and social betrayal involved in the crime. It stated that instead of showing fatherly love, affection and protection to the child against the evils of society, the appellant made her the target of an unimaginable act of violence. This, the court said, was a case in which trust was gravely betrayed and social values were severely impaired.

The judgment described child rapist Ghumare’s conduct as reflecting a “dirty and perverted mind” and called the incident a “horrifying tale of brutality”. The judges made it clear that such crimes are not only offences against an individual child and her family but also a deep wound to the collective conscience of society. In this context, they held that the extreme penalty of death was justified.

After the Supreme Court’s confirmation, the only remedy left to the convict was to seek mercy from the President of India. A mercy petition does not question the legality of the conviction or the sentence. Instead, it is a constitutional provision that allows the President to consider factors such as the convict’s background, mental condition, remorse, time spent on death row and any other humanitarian or public considerations.

In this case, the mercy plea was placed before President Droupadi Murmu and, according to the status disclosed by Rashtrapati Bhavan, was rejected on November 6, 2025. Officials confirmed this decision on Sunday, noting that the President had considered all relevant materials before declining to commute the death sentence.

With the rejection of the mercy petition, the judicial and constitutional process has effectively reached its conclusion. The authorities may now proceed, in accordance with the law, to carry out the death sentence, following all established procedures and safeguards. The rejection also adds to the evolving record of how the Indian state responds to a child rapist or the most brutal crimes against children.

The case once again brings into focus the debate around punishment for sexual offences, especially those involving minors. Supporters of the death penalty in such cases argue that it acts as a necessary and powerful deterrent, sends a strong message of zero tolerance and offers a sense of justice to the victim’s family and society at large. Opponents of capital punishment, however, often question its deterrent value and raise concerns about irreversible punishment.

However, in situations like the Jalna child rape and murder case, the judicial language and the President’s decision highlight the view of the state that certain crimes are so monstrous that they demand the harshest possible response. Here, the courts and the President have spoken in one voice, treating the crime of a child rapist, brutal assault and killing of a two year old as a crime beyond the bounds of ordinary leniency.

As the legal chapter closes, the memory that remains at the centre of this case of child rapist is that of a small child whose life was destroyed before it had a chance to flourish. The institutions of the state have responded with the severest punishment available under the law, seeking to mark society’s absolute condemnation of such unspeakable violence.