Prime Minister Narendra Modi, speaking from the ramparts of the Red Fort on Independence Day, called the 1960 Indus Water Treaty “unjust and one-sided.” His words rekindled a long-standing debate that dates back to the time of Jawaharlal Nehru himself, when even Parliament was largely against the deal. A dominant view across the political spectrum at the time was that India had sacrificed far too much, leaving its farmers and future generations to pay the price.

What many do not recall is that when the treaty was signed, it was done without consulting Parliament, and by the time MPs debated it, the pact was already ratified. The Indus deal became one of the sharpest points of criticism faced by Nehru in his career, drawing fire not just from opposition figures like a young Atal Bihari Vajpayee but also from within the Congress benches.

The story of the Indus Water Treaty is not just about water. It is about how a nation’s leadership chose appeasement over national interest, and how that choice has cast a shadow over India’s development and security for more than six decades.

The Treaty: What Nehru Signed Away

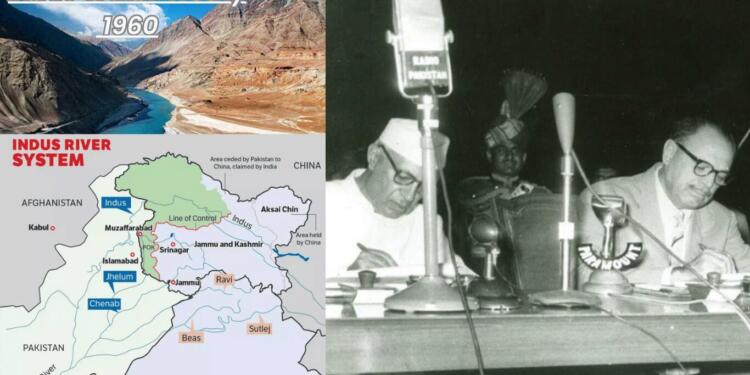

The Indus Water Treaty was signed on September 19, 1960, in Karachi by Nehru and Pakistan’s military ruler, President Ayub Khan, with the World Bank acting as a guarantor.

Under the agreement, the waters of the three eastern rivers Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej were allocated to India. The three western rivers Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab were given to Pakistan. More importantly, India was obliged to pay ₹83 crore in sterling pounds to Pakistan for replacement works, despite facing its own foreign exchange crisis at the time.

This effectively meant India was left with control of only about 20% of the total waters of the Indus basin, while Pakistan walked away with the lion’s share around 80%. Nehru hailed the deal as an example of cooperation, but MPs from across the spectrum described it as “a sell-out,” “a second partition,” and a “grave injustice to Indian farmers.”

The criticism was not about water alone. It was also about the principle: why was India giving away such a critical resource to a hostile neighbour, especially without consulting Parliament or linking it to the larger issue of Jammu and Kashmir?

Nehru Versus Parliament: “A Second Partition”

On November 30, 1960, the Lok Sabha debated the Indus Water Treaty. Ten members moved motions against it. Just two hours were allotted, but the interventions made in that short time revealed the extent of dissatisfaction.

Even Congress MPs were scathing. Harish Chandra Mathur warned that the treaty meant perpetual losses to Rajasthan to the tune of ₹70–80 crore annually, describing it as an act of “over-generosity at the cost of our own people.” He accused the Prime Minister of surrendering step by step to Pakistan since 1948 and failing to link water settlement with Kashmir.

Asoka Mehta, another Congress stalwart, likened the treaty to a “second partition”, warning that it reopened wounds of 1947. He noted that instead of securing a fair deal, India had actually ended up with worse terms than earlier proposals, calling it a blunder that would haunt future generations.

A.C. Guha, from Bengal, pointed out the glaring imbalance: India had 26 million acres in the Indus basin but only 19% of it irrigated, while Pakistan’s 39 million acres had over 50% irrigation. He criticised the financial terms too Pakistan received more than ₹400 crore in grants, while India was saddled with loans. He called the ₹83 crore payment to Pakistan “the height of folly” at a time when India itself was struggling.

These were not voices of the opposition alone. They came from within Nehru’s own party, reflecting a deep unease at the manner in which the Prime Minister had bypassed Parliament and compromised India’s interests.

Vajpayee’s Warning: “This Treaty is Wrong”

Among the strongest critics was a young Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then in his early 30s. Speaking with clarity and conviction, Vajpayee reminded the House that the government had earlier announced it would stop waters to Pakistan by 1962. Now, the same government was conceding permanent rights. “Either that announcement was wrong, or this treaty is wrong,” he said pointedly.

Vajpayee quoted Ayub Khan, who had boasted that India had conceded joint control of rivers. He warned that such concessions would embolden Pakistan further and undermine India’s sovereignty. Importantly, Vajpayee also criticised the secrecy surrounding the deal, noting that Parliament had been deliberately kept in the dark until it was a fait accompli.

His conclusion was sharp: “This treaty is not in the interest of India. It will not bring lasting friendship with Pakistan.”

Those words would prove prophetic. Far from creating goodwill, Pakistan continued its hostility, sponsoring terrorism and wars against India while benefiting from a treaty that guaranteed it waters from the Indus system.

Nehru’s Defence: A Lonely Stand

When Nehru rose to reply, he appeared weary and defensive. He dismissed comparisons with partition as “meaningless language,” even mocking the criticism by asking, “Partition of what? A pailful of water?”

He argued that international treaties could not be run through constant parliamentary consultation and justified the payment to Pakistan as “purchasing peace.” According to him, rejecting the treaty would have destabilised West Punjab and the broader subcontinent.

But his reasoning failed to convince. He left the chamber soon after, to meet a visiting dignitary, leaving behind a dissatisfied House and a growing perception that India had been shortchanged.

The Legacy and Modi’s Course Correction

For decades, the IWT remained untouched, even as Pakistan continued to bleed India through proxy wars and cross-border terrorism. Farmers in Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Jammu & Kashmir bore the brunt of water scarcity while Pakistan reaped the benefits of India’s concessions.

The criticism voiced in 1960 never really disappeared. It found new resonance in later years, especially as Pakistan intensified its hostility.

Finally, in 2025, after the Pahalgam terror attack, Prime Minister Narendra Modi decided to put the treaty into abeyance. His government has signalled that India will no longer allow its resources to be taken for granted by a neighbour that openly supports terrorism. Modi’s words at the Red Fort that the treaty was unjust and caused immense harm to India’s farmers echoed the warnings of Vajpayee and other leaders who had opposed Nehru’s deal six decades earlier.

Learning from History

The Indus Water Treaty remains a striking example of how leadership decisions can shape a nation’s destiny for generations. Nehru’s eagerness to be seen as a statesman led him to sign away critical resources without Parliament’s approval, and India has paid the price ever since. His critics Vajpayee, Asoka Mehta, Guha, and many others had seen the dangers clearly.

Prime Minister Modi’s decision to revisit the treaty is not merely about water. It is about correcting a historic wrong, asserting India’s sovereignty, and ensuring that national interest is never sacrificed for misplaced idealism.

In 1960, India was forced to accept a deal that many called a “second partition.” In 2025, under Modi, India has begun to undo that legacy, guided not by appeasement but by self-respect and strength.