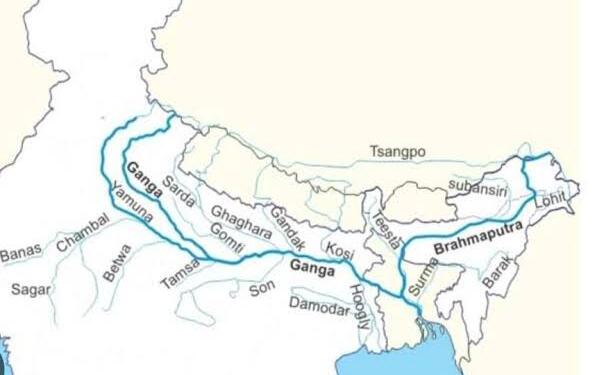

The Ganga is more than a river. It is a lifeline, a legend, and a legacy. Rising in the icy heights of the Himalayas and winding its way through the plains of northern India into Bangladesh, the Ganga sustains over 600 million people. It irrigates fields, powers cities, nourishes ecosystems, and inspires spiritual devotion across two nations. But as the river’s flow thins under the weight of rising demands and a changing climate, its waters have also become a source of tension.

For nearly three decades, the 1996 Ganga Water Sharing Treaty between India and Bangladesh has helped manage this delicate balance. It has endured political changes, economic transformations, and environmental shocks. But it was designed for a different era- one where climate change was a distant threat, and regional geopolitics were less fluid.

Now, as the treaty’s 30-year term nears its end in December 2026, the clock is ticking. And 2025 must be the year India steps forward, not only as the upper riparian power, but as a regional leader ready to shape the future of shared water governance.

A Treaty Born of Hope

In 1996, the signing of the Ganga Water Sharing Treaty was a diplomatic breakthrough. After decades of disputes, especially following the construction of the Farakka Barrage in 1975, India and Bangladesh finally found a framework for cooperation. The treaty created a formula for water allocation during the dry season, aimed at satisfying both India’s industrial and navigational needs and Bangladesh’s agricultural and ecological demands.

The treaty was not just about numbers; it was a commitment to trust and cooperation. By agreeing to share real-time water flow data and resolve disputes through the Joint Rivers Commission (JRC), both countries took a step toward peaceful, rules-based water management in a region where such examples are rare.

The Cracks Begin to Show

But nearly 30 years on, the foundation of that treaty is showing signs of strain.

The Ganga’s dry season flows have dwindled. Climate change has altered rainfall patterns, glaciers are retreating, and upstream water use including in Nepal, which remains outside the treaty framework is reducing downstream availability. The historical flow data the treaty relies on (1949–1988) is no longer a reliable guide.

Meanwhile, socio-economic pressures are intensifying. In India, states like West Bengal and Bihar are demanding more water for agriculture, drinking water, industry, and power generation. The Farakka Barrage, meant to rejuvenate the Kolkata Port, is itself facing siltation and declining efficacy. In Bangladesh, reduced flows are threatening rice cultivation, fisheries, and the fragile Sundarbans delta- one of the world’s most vital ecological hotspots.

At the same time, institutional mechanisms like the JRC have struggled to keep pace with rising complexity. Meetings are irregular, decisions are slow, and enforcement is weak; especially during low-flow periods when disputes are most likely.

The world has changed. The treaty has not.

2025- A Defining Moment

The window for action is narrowing. Renegotiating a treaty of this scale isn’t just a legal exercise; it demands years of technical studies, political consensus-building, and delicate diplomacy. Waiting until 2026 would be a gamble. Starting in 2025 is not just strategic, it is essential.

India has already signaled a shift. In June 2025, the Indian government proposed a shorter, more adaptive treaty (10–15 years), reflecting the need for flexibility in a volatile hydrological future. But Bangladesh is pushing back, demanding stronger guarantees for minimum flows. Domestic pressures are mounting on both sides of the border, and regional trust is fragile; especially after India suspended the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan earlier this year.

At stake is more than just a water-sharing formula. This is about India’s credibility, leadership, and its vision for regional cooperation in an age of water scarcity.

Why India Must Lead

India is uniquely positioned to lead this transformation- technically, diplomatically, and morally.

Technological Edge: India has some of the most advanced hydrological research and water data capabilities in the region. It can spearhead real-time flow monitoring, climate forecasting, and adaptive water allocation models.

Domestic Stewardship: A renewed treaty offers India a chance to address the concerns of its own states like West Bengal and Bihar through inclusive, federal consultations. Empowering these stakeholders strengthens the treaty at home.

Geopolitical Standing: With China increasing its influence in South Asian river politics (including in Bangladesh’s Teesta Basin), India has every reason to reaffirm its leadership. A fair, future-ready Ganga Treaty would be a powerful counterweight to external interference.

Regional Integration: India’s larger vision of a connected, cooperative South Asia depends on building trust. By proposing joint projects, such as inland water navigation or regional energy sharing, India can turn a water-sharing dilemma into an opportunity for growth.

Global Responsibility: The world is watching. Transboundary river governance is a litmus test for climate cooperation. A modern, equitable Ganga Treaty could set a new global benchmark, echoing principles from the UN Watercourses Convention.

A Vision for the Future

A renewed Ganga Treaty must do more than just divide water. It must manage a river basin under stress and a region in flux. India can lead the way by advocating a treaty that includes:

Climate Resilience: Flexible allocations based on updated flow data, with minimum environmental flows protected.

Basin-Wide Thinking: Engaging Nepal to manage upstream abstractions and build a holistic Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna framework.

Stronger Institutions: A reformed JRC with dispute resolution powers, regular reviews, and enhanced transparency.

Benefit Sharing: Joint ventures in navigation, hydropower, or climate resilience that benefit both nations.

Public Engagement: Transparent consultations with Indian states and civil society, fostering consensus at home while respecting regional commitments.

Turning the Tide

The Ganga flows through the heart of India but also through the heart of its relationship with Bangladesh. For centuries, its waters have united cultures, communities, and civilizations. The next chapter in this shared history will be written not by the river’s course, but by the choices India makes in 2025.

This is more than a treaty renewal. It is a test of vision, responsibility, and statesmanship. If India rises to the occasion with empathy, intelligence, and resolve, it can forge a new model of cooperation for a climate-challenged world.

The Ganga calls. India must lead.