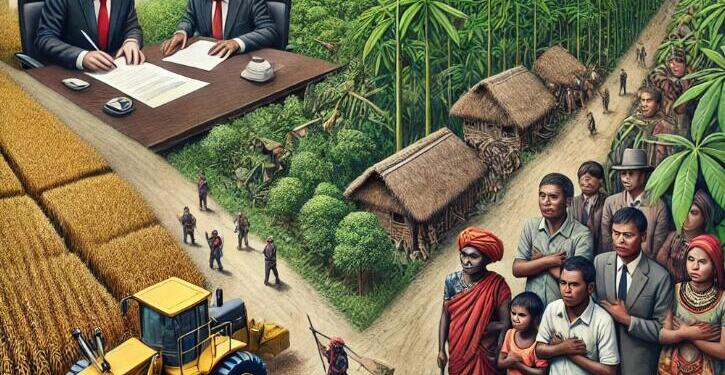

Large-scale land grabbing throughout Africa, Latin America, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia countries have worsen social injustices and has widen economic gaps, making land grabbing a serious concern that is impacting the indigenous communities. In this phenomenon, large areas of arable land that were previously utilized by local populations for subsistence farming are purchased or leased by foreign and domestic investors, that are often supported by government policies aimed at economic development.

A concerning pattern of human rights abuses, environmental damage, and displacement linked to these investments is demonstrated by recent events in both regions. For instance, the increasing corporate interests in Africa has resulted in vast acquisition of communal lands for purposes like carbon offsetting, thereby disregard for the rights and livelihoods of indigenous people.

Similarly, in Southeast Asia, the increasing demand for agricultural land, fueled by global markets for cash crops and biofuels, causes major land disputes and social unrest among local populations. While a failed attempt to lease 1.3 million hectares in Madagascar has garnered a lot of media attention, deals that are reported in news are only the tip of the iceberg. Given how important land is to identity, livelihoods, and food security, this is rightly a hot issue.

LAND GRABBING OR DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY?

Large-scale land grabbing are a contentious phenomenon that frequently walks a fine line between being seen as a land grab and a developmental opportunity. Proponents of these acquisitions frequently claim that the investments can result in increased agricultural productivity, infrastructure development, and economic growth. And properly managed large-scale agricultural investments can promote technology transfer, job creation, and improved food security for host nations.

However, critics draw attention to the negative effects that frequently outweigh these alleged advantages. Many times, local communities are evicted from their ancestral lands, which disrupts traditional farming methods and causes them to lose their means of subsistence. Therefore, as rural populations face uncertain futures amid the push for large-scale land deals, the line between land grab and development opportunity becomes increasingly blurred, raising fundamental questions about whose interests are truly served here.

FACTORS BEHIND GROWING INTEREST IN LARGE-SCALE LAND ACQUISITION

These land purchases appear to be motivated by a number of factors. One of the main factors influencing government-backed investment is food security, especially in investor nations. The expansion of biofuel production, a significant competing land and crop use, bottlenecks in storage and distribution, and limitations in agricultural production brought on by a lack of water and arable land all contribute to issues and uncertainties in the food supply. Global food demand is also rising as a result of shifting dietary habits and rising rates of urbanization.

New patterns of land investment are also being driven by the demand for biofuels and other non-food agricultural commodities worldwide, expectations of increasing agricultural rates of return and land values, and policy measures in both the home and host countries. Financial incentives and government consumption targets—such as those in the European Union—have been major motivators for the use of biofuels.

The recent drop in oil prices from their 2008 peak could potentially stifle interest in biofuel investments. However, unless policies change in response to worries about the effects of biofuel expansion on food security, biofuels are likely to continue to be an option in the long run, especially given the forecasts of declining non-renewables supplies.

Regarding rates of return in agriculture, the purchase of land for agricultural production appears to be a more alluring option as a result of rising commodity prices. To go upstream and into direct production, some agribusiness companies that have historically worked in food processing and distribution are pursuing vertical integration strategies.

Even though political risk is still high in many African and Southeast Asian nations, policy changes have made the investment climate more appealing in a number of these nations. These changes include the creation of more investment treaties and codes, as well as the revision of sector-specific laws pertaining to banking, land, taxes, customs, and other areas.

ADDRESSING RISKS AND SEIZING OPPORTUNITIES

People in recipient nations face both opportunities and risks as a result of this scenario. Macroeconomic benefits like GDP growth and higher government revenues could result from increased investment, which could also open doors for rural communities’ economic growth and standard of living. However, as markets or governments open up land to potential investors, large-scale land purchases could cause locals to lose access to the resources they rely on for their food security, especially since some important recipient nations are already struggling with food security.

Many times, land is already being used or claimed, but because land users are excluded from formal land rights and institutions, their claims and uses are not acknowledged. Furthermore, when demand shifts toward higher-value lands (such as those with better irrigation potential or proximity to the markets), large-scale land allocations may still lead to displacement even in nations with some available land. The terms and conditions of international land deals ultimately determine how well opportunities are taken advantage of and risks are reduced.

Host country benefits are mainly seen in the form of investor commitments on investment levels, employment creation and infrastructure development though these commitments tend to lack teeth in the overall structure of documented land deals. Even though on paper some countries have progressive laws and procedures that seek to increase local voice and benefit, big gaps between theory and practice, between statute books and reality on the ground result in major costs being internalised by local community.

Many countries do not have in place legal or procedural mechanisms to protect local rights and take account of local interests, livelihoods and welfare. Even in the minority of countries where legal requirements for community consultation are in place, processes to negotiate land access with communities remain unsatisfactory. Lack of transparency and of checks and balances in contract negotiations creates a breeding ground for corruption and deals that do not serve the public interest.