The rupee has been falling for quite a few months now. The media and every other expert are going gaga over it. Some call it the government’s failure, while others blame it on the global slowdown. Very few talks about the silver lining of the falling rupee. The fact is that a weak rupee also means that Indian manufacturers can send more products to the international market and earn more in rupees. For that, we need to have a competent manufacturing sector. This is where we are lacking.

GDP numbers and concerns

Recently, India’s October-December GDP numbers came out. The only recession-proof country in the world recorded a meagre growth of 4.4 percent. There are various factors behind it. For nearly a year, the RBI has prioritised inflation over growth. Secondly, the base effect provided by low COVID numbers has eroded, in a way making the growth rate a victim of its own success.

The third and most worrying reason is the failure of Indian domestic manufacturers to rise to the occasion. India’s Purchasing Managers’ Index in manufacturing was recorded at 55.3, the lowest in four months. It is an index of the prevailing direction of the sector. In terms of year-on-year growth, manufacturing output witnessed a decline of 1.1 percent. Its share in overall GDP has also not witnessed the expected uptick.

Also read: The next decade of iPhone manufacturing belongs to India

Historical problem with manufacturing

There is no doubt that the manufacturing sector has not been able to contribute to its fullest capacity. There are multitudes of reasons behind it. For one, the history of manufacturing in India has not been particularly boastful. In fact, if we take three decades after the IMF enforced LPG reforms in 1991, the disappointment increases in significant proportions.

Just after independence, manufacturing was not an immediate priority. Therefore, it remained somewhere on the backburner in policy circles. Few industries in close proximity to establishments were able to establish factories, while others either became managers or unregulated daily wage workers. Consequently, oligopoly kicked in. Maybe it was our best option in those days, and in terms of absolute growth rate, manufacturing did increase.

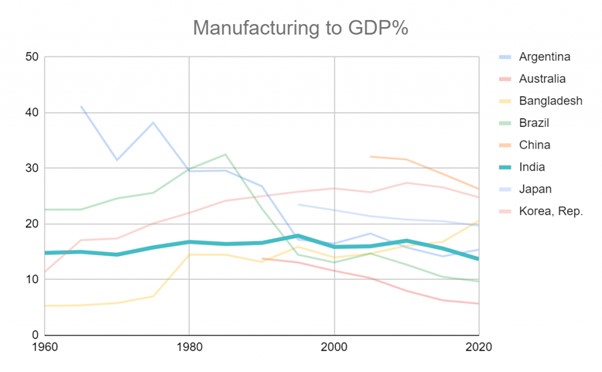

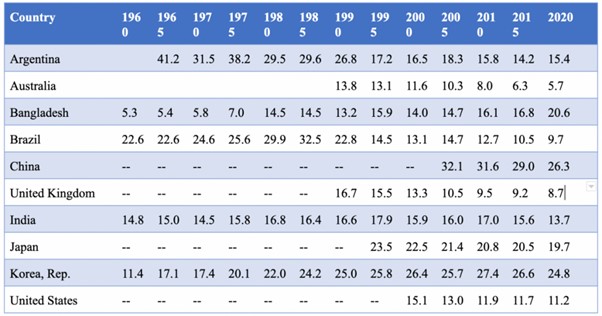

The disappointing aspect of it is that, as a share of GDP, the sector is almost stagnant. Look at the trajectory of the blue line in this chart on the screen. While in 1960, manufacturing’s share in India’s GDP was nearly 15 percent, in 2020, it was lower than that. Peak was observed in the 1990s, just a few years after LPG. The sentiments quickly died down.

PC: TheWire

Also read: HAL excels at manufacturing, but it needs to up the ante in marketing

Now, compare it with that of other countries having similar demographic and industrial make-ups. Look at the chart on your screen. South American countries like Argentina and Brazil peaked in the 1970s and 1980s. China’s peak came in 2005, when its manufacturing sector contributed 32.1 percent of its GDP. Its East Asian neighbours like Japan and South Korea have also witnessed a sharp uptick.

CP: TheWire

The share of manufacturing in these countries’ GDP started to decline only when they reached a certain level of prosperity, as the service sector kicked in. To put it simply, there are stories of up and then there are stories of downward spiral after an uptick.

But, none of these countries have stagnant manufacturing with respect to its share in GDP. While between 2000 and 2008, there was some hope in the sector, the global financial crisis of 2008 and policy paralysis in subsequent years only worsened it. News like the shifting of Tata Nano’s manufacturing plants contributes to declining sentiment.

Also read: How India’s resilient economy is boosting India’s manufacturing capability

Changes after 2014

When the government changed in 2014, there was a lot of crap to clear. India was not doing well on the ease of doing business. We could not provide a stable electricity connection, nor could we take measures to ramp up production. Land acquisition was another big hurdle for industries. The regulatory regimes and documentation process was painstakingly slow. Logistical costs, including transportation of raw and finished goods, were not good either. Besides them, there was no government support to start or continue production.

There is no way you can expect companies to invest in manufacturing. The heavy lifting had to come from the government. Nationalist sentiments also demanded a call for it. During the UPA years, imports from China had increased by a humongous 1,175 percent.

To resurrect the dead, initiatives like Make in India, “Atmanirbhar Bharat, Standup India, and Startup India are there along with various other schemes to promote MSMEs as feeders to the chief manufacturing segment. They contribute about 30 percent to the Indian GDP.

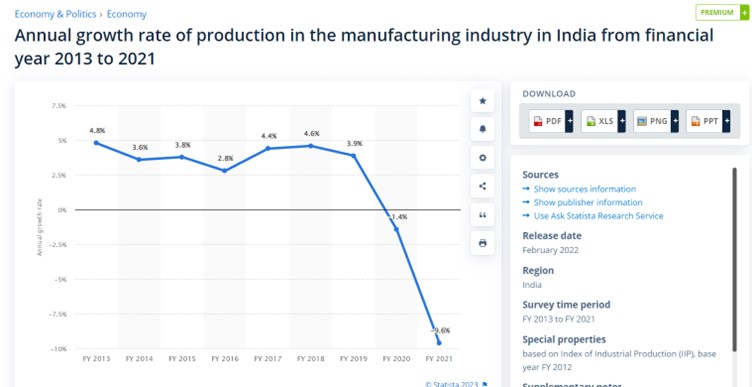

Unfortunately, these initiatives did not succeed at all. In fact, in FY15 and FY16, the growth rate of production in manufacturing only declined to 3.8 and 2.8 percent, respectively. It did increase to 4.6 percent in 2018, but hey, that’s like a drop in the ocean. That is because India was and is in desperate need of manufacturing to take off.

Also read: How PM Modi transformed India into an Agarbatti manufacturing hub

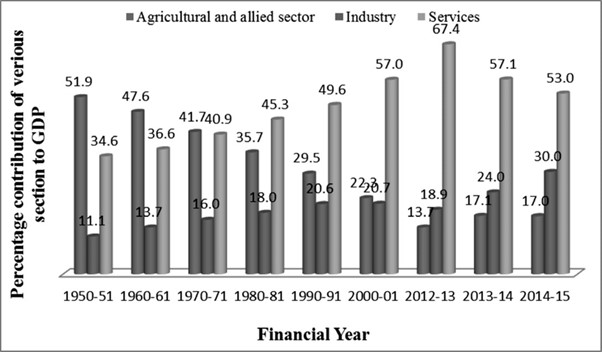

India skipped the manufacturing journey

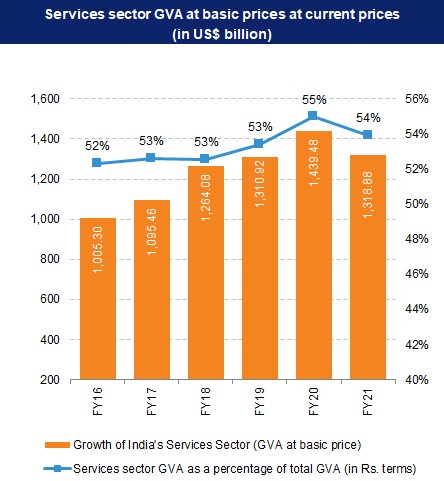

See, the problem with India is that it is the rarest in the world when it comes to the share of industries in GDP growth. India’s service sector matured way before manufacturing. For the last decade or so, its share in the GDP has always remained above 50 percent. The percentage share of its GVA in total GVA has also seen the same trajectory.

PC: Researchgate

PC: IBEF

The issue with the service sector taking precedence over manufacturing is that it does not have the capacity to provide many jobs. Sure, it does provide quality and relatively comforting jobs. You can sit at a computer and earn more than the average worker. But your job is more skill-based. The majority of our workforce is not fully skilled. Only manufacturing has the capacity to absorb them.

Apart from the aforementioned problems, the distribution of existing manufacturing capacity is another big one. 60 percent of our states contribute to only 20 percent of total productivity. On the other hand, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu account for 40 percent of the total value. Consequently, the need for transportation from one state to another remains a perennial problem.

PC: BQ PRIME

Also read: How WTO is manufacturing world hunger

Problem with the current dispensation

And these are two spots where the Modi government’s initiatives in manufacturing could not work. Only Rajasthan has been able to compete with the aforementioned states in grabbing manufacturing investment. And that too because of its access to 40 percent of the market in the most populous state of India.

Again, the issue is directly related to transportation. 71 percent of the country’s freight is handled by road, while only 17.5 percent and 11.5 percent are handled by rail and waterways, respectively. These figures are nowhere near the global standard. For an efficient logistical sector, 25–30 percent of freight traffic should be handled by road. Railways, as a faster mode of transportation, should handle more than half of all traffic, with the remainder handled by waterways.

The ultimate responsibility falls on the central government. In the last 8 years of the Modi government, the pace at which roadways have developed is in no way comparable to the railways. By the end of 2021, more than 1,41,000 km of road had been built by the government. On the other hand, freight traffic as a share of the railroads has not witnessed such growth.

The principle of absolute liability places the blame squarely on the Modi administration’s Railway Ministry. But we have to take into account that we are speaking from the vantage point of trains running on time in 2023. That was not the case in 2023. A 24-hour delay was common. Industries can’t afford that. Riding on the success of improved timing, the government has devised a plan to increase the share of freight traffic from 27 percent in 2022 to 45 percent in 2030. It may be more realistic, but 50 percent would be a more attainable target.

Also read: India’s defence manufacturing just got a massive upgrade

Required changes and the government’s willingness to change

To make it possible, high-speed rail networks are the need of the hour. It will only make our manufacturing more competitive. A 200-kilometer train journey connecting factories with raw materials takes barely an hour in China. Other manufacturing greats like Germany also have a well-managed rail network.

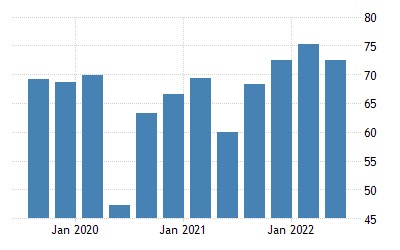

No wonder, capacity utilisation in German manufacturing is as high as 84.10 percent, while in China it is 75.70 percent, which is on the decline. In India, the corresponding figure keeps hovering between 70 and 75 percent, an improvement that is, to be honest, more worrying.

PC: Tradingeconomics

Clearly, due to the time spent correcting historical wrongs, the Indian government’s push towards manufacturing needs constant reshuffling. Right around Pandemic, it came up with an outlay of 1.97 lakh crore under the production-linked incentive scheme. Budget allocations for ministries like defence and railroads, which have key roles in manufacturing, are increasing at a good pace.

Under the national manufacturing policy of 2011, a new concept called the National Investment and Manufacturing Zone has been added. This is in addition to reorienting SEZs towards the local market. Last year, the National Logistic Policy was launched to decrease the government’s spending on logistics from 14–15 percent of GDP to 8 percent.

Also read: The growth story of India’s defence manufacturing under PM Modi

Industries need to wake up from their slumber

But the government can’t do it alone. It needs support from local industries. That is lacking. Bluntly speaking, the Indian business sector is lacking nationalistic sentiment as a whole. The community is just not ready to contribute their best. And that is when the sector holds so much promise.

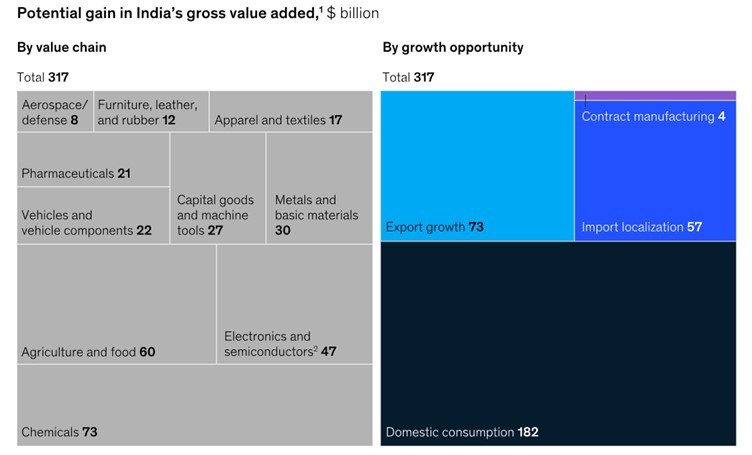

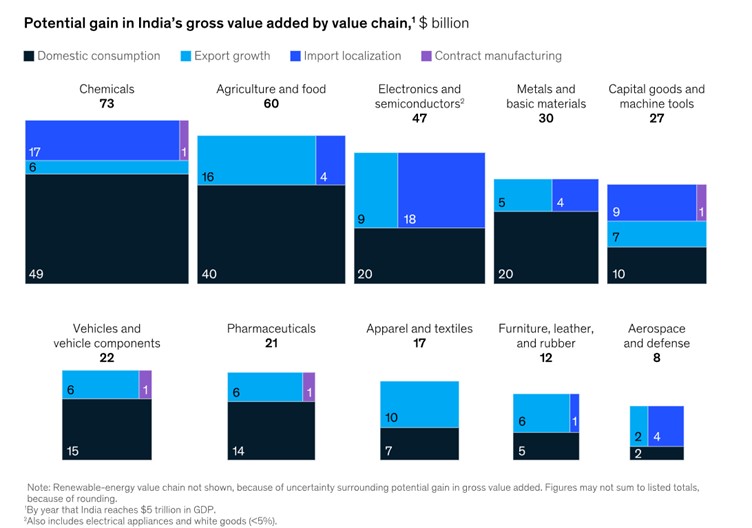

According to a 2020 McKinsey analysis, scaling up only 10 sub-domains of manufacturing can push GVA by $320 billion. It found that growth in the domestic market can provide another $180 billion, while export growth can contribute $70-75 billion to GVA. Import localization and contract manufacturing can add another $65 billion.

PC: Mckinsey

PC: Mckinsey

The potential, along with a well-intentioned push by the government, is not proving enough for industries. To be honest, they have their reasons for not relying on the government, but if 8 years and so much change are not enough, one wonders what is enough for these companies to go all out.

In the last few months, frustration that office bearers have been holding came out into the open. A few days ago, Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal lamented the fact that Indian businesses are increasing the trade deficit by importing for as little as 2 percent profit. He asked them to be helpful and supportive towards local manufacturing.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had to publicly ask for their discomfort with the dispensation. She even applied the term “manufacturing to that part of Bhagwan Hanuman’s life when he had not realised his potential. The government is being Jamwant in this case. Wonder when it will fructify?

Support TFI:

Support us to strengthen the ‘Right’ ideology of cultural nationalism by purchasing the best quality garments from TFI-STORE.COM