In the last few decades, the Judiciary of the country has enjoyed enormous power with zero accountability. The institution, as one of the pillars of the democracy, plays an important role in socio-political system of the country. An independent Judiciary is indispensable for any modern democratic country, but, the independence should not come at the cost of accountability.

The Attorney General of India, KK Venugopal, reminded the Supreme Court of accountability when the apex court questioned the government over delay in appointment of judges. “Let high courts reform themselves first. Why question the government for 100-odd days in vetting a name when high courts take five years in sending names for appointments?” the Attorney General told the court.

The Supreme Court headed by Justice K Kaul asked the government’s lawyer to demonstrate the timeline of judicial appointment in Supreme Court and High Courts. The data, as presented by the government, revealed that, the government takes 127 days to clear a name. When the Court questioned this delay, the AG retorted by saying that Supreme Court Collegium system itself takes 119 days just for clearance of a name despite having all the reports. After that, Justice Kaun was on back foot and he accepted that 40 percent of the seats in the High Courts are lying vacant, said the AG.

Judiciary has always been accused of being among the most unproductive institutions of the country with backlog of lakhs of cases, and this is dragging up the Indian economy. Last year’s Economic Survey has a chapter titled as ‘Ending Matsyanyaya: How to Ramp up Capacity in the Lower Judiciary’ draws attention towards an important issue prevalent in Indian system and that is ‘enforcement of contracts’. The chapter starts with “The Rule of Law and maintenance of order is the science of governance” a quote by Kautilya in his much-celebrated work, Arthashastra.

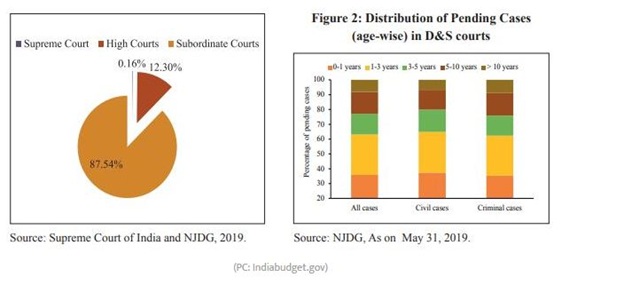

According to the chapter, in the country, more than 3.5 crore cases are pending in courts. Majority of these cases are in the district and subordinate courts. The chapter further argues that the country is following the law of the jungle or Matsyanyaya (where big fish eats small fish) due to the inefficient court system.

The survey further states that the majority (87.54 percent) of the cases are pending in district and subordinate courts. More than 64 percent of the total cases are for more than one year and number of cases (in percentage) pending for more than 10 years is in double digits.

One interesting and much-expected finding is that poorer states have high pendency compared to richer states. The states with the highest pendency are Odisha, Bihar, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh. The disposal time which is measured as the time span between the date of filing and the date when the decision is passed is also higher for poorer states like Bihar, Odisha and West Bengal.

According to the survey, “Simulations of efficiency gains and additional judges needed to clear the backlog in five years” and 100 percent clearance rate (ratio of the number of cases disposed of in a given year to the number of cases instituted in that year) by merely filling out the vacancies in the lower courts and in the High Courts. The Survey also mentions that states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, and West Bengal need special attention in the enforcement of contracts.

The survey also argues that the Indian courts could be made more productive by increasing the number of working days, the establishment of Indian Courts and Tribunal Services, and Deployment of Technology.

As India aims to achieve 8 percent compound annual growth rate, it cannot afford to have more than 3.5 crore pending cases. The country cannot afford to have 163 rank in the enforcement of contracts and call itself just and judicious. To become a 5 trillion dollar economy by 2024, the country needs to achieve 100 percent clearance rate and clear the backlog of unproductive years.

The AG rightly pointed out that the Judiciary needs to reform itself first before teaching other lessons about efficiency and questioning the late-latifi in the appointments by the government.