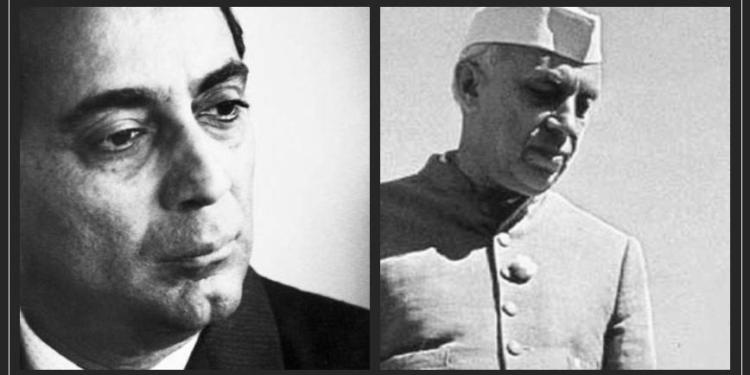

In 1948, a Cambridge graduate in theoretical physics, a Royal Society fellow and the then head of Tata Institute of Fundamental Research convinced India’s the then Prime Minister, Jawahar Lal Nehru to set up Atomic Energy Commission to advance research in nuclear physics. The nuclear race was still in nascent stage and the nuclear monopoly lied with United States even after three of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But this young Indian scientist knew the unfathomable power of the atom and more importantly its strategic value. The young scientist was Dr. Homi Jahangir Bhabha. The Indian Nuclear Weapons program traces its history with the establishment of Atomic Energy Commission in 1948 with Dr. Homi Bhabha as Founding Chair. While Homi Bhabha was a proponent of acquisition of nuclear weapons, Prime Minister of India had an ambiguous stance on the issue. While he had earlier stated his favour towards research in nuclear physics, he had staunchly refused to entertain the possibility of India acquiring nuclear weapons. The dichotomy of strategic interests vs internationalist, idealist foreign policy was nowhere starker than Nehru’s stance on nuclear weapons. When it came to choosing between securing India’s strategic interests through well-developed nuclear arsenal and securing his legacy that of a ‘peacenik’ and ‘internationalist’, Nehru invariably chose the latter. The early years of Indian Atomic development were largely marked by nuclear co-operation with Canada, USA, UK and France and focused towards peaceful use of Nuclear Energy. However, Bhabha had recognized the immense possibility of the weapon and its strategic value. During a conference, he stated “Nuclear weapons coupled with an adequate delivery system can enable a State to destroy more or less totally the cities, industry, and all-important targets in another State. It is then largely irrelevant whether the State so attacked has greater destructive power at its command. With the help of nuclear weapons, therefore, a State can acquire what we may call a position of absolute deterrence even against another having a many times greater destructive power under its control.” Under Homi Bhabha, the scientific community started lobbying for the bomb and as is evident, it was Bhabha himself who was most vocal about nuclear aspirations. However, Nehru’s ambivalence on nuclear decision making continued to be the brick wall against which the scientific community kept running into.

Nehru not only resisted the continued push for nuclear arms by the scientific community, his misguided idealism prevented India from securing a nuclear technology transfer from US. As Former foreign secretary Maharajkrishna Rasgotra reveals in his book, Nehru not only had turned down United States’ offer of permanent seat in the UN but had also turned down an offer by US president of nuclear technology transfer to India. Had Nehru been more concerned about securing India’s strategic interests rather than pushing for his by then increasingly untenable idea of NAM, India could have become a nuclear power way earlier. In fact, India’s current problem of securing NSG membership would have also been solved way earlier had Nehru been more receptive to Kennedy’s offer. Nehru failed to understand that in international politics power and national interests override any utopian ideals of internationalism, a fact he would learn the hard way in 1962. Alas! Neither Nehru heeded Homi Bhabha’s call for indigenous nuclear weapons development nor he accepted the technology transfer from Kennedy and for his follies, India paid a heavy price in 1962 and continues to be at a disadvantage even now.