While the naysayers of PM Modi’s flagship programme “Make in India” continue to dub it as a failure of massive proportions and just a slogan, PM Modi true to his promise, has made indigenous defence production the heart of Make in India and the results are finally showing up.

The Indian Army under the previous UPA regime has faced severe shortages and various delays in procuring equipment due to red tape and rampant corruption which led to the Army using outdated equipment. Come 2014, Narendra Modi made it his personal mission to significantly improve the Army’s condition and with rising threats from China and Pakistan, a two-front war with China and Pakistan being a real possibility now, defence procurement has never been more important.

In a bid to change the status quo, the government introduced a new defence procure meant policy (DPP) which was effective from 2016 and increased the Foreign Direct Investment in defence. As soon as the Modi government was sworn in, the FDI in the defence industry was increased to 49% from 26%. However, the FDI in 2015-16 was just about INR 56 lakh thereby forcing the government to act allowing FDI up to 100% in some cases where the country would witness the latest technology transfer. Under the brand new DDP, a product will be required to have at least 40% indigenous content if it is designed in India or at least 60% indigenous content if the design is not indigenous, making it the most preferred category.

India had the ignominy of having Defence Ministers like Mulayam Singh Yadav in the past who are best known for their caste-based politics and their only ideology is corruption. In an attempt to not let the day to day dealings of the Army to lie on the whims of a Minister, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion(DIPP) is constituted to exclusively issue licenses making it the final authority to issue licenses and not the Defence Minister.

Following the Central government’s footsteps and recognizing the huge potential from the defence sector, several states are also offering incentives and concessions in the form of aerospace clusters or Special Economic Zones (SEZs) for developing an ecosystem where all core and ancillary activities related to defence manufacturing can co-exist.

The government also met recent success by procuring Rafale jets from Dassault Aviation which would be modified to the Indian Airforce’s(IAF) needs after government to government negotiations between India and France. It is important to note that the same jets were stuck during the UPA regime due to red tape and massive corruption and the IAF never received the Dassault jets as promised earlier.

It’s no secret that India is the largest importer of defence equipment in the world. Despite this fact, the IAF is still operating on Soviet-era aircrafts such as MiG 21s and MiG 27s which have long been discarded by the rest of the world. The condition of these jets is so poor that they have been dubbed as “Flying Coffin” and “Widow Maker”. While the first fleet of Dassault Rafaela jets will only arrive in 2019, the Government has moved swiftly to replace the entire fleet of aircraft and is in talks with both American company, Lockheed-Martin, the manufacturer of F-16 jets and Swedish company Saab, the manufacturer of Gripen jets. Both the companies have agreed to provide 126 aircrafts to India and it’s up to India now which jet it would like to have. Whichever jet India chooses, it will have a thumbprint of Make in India as the jets will be manufactured on Indian soil thus creating thousands of job and massive technology transfer. This has led to Lockheed-Martin partnering with Tata to produce F-16s in India and is ready to sell the latest variant i.e.block 70 to India whereas countries like Pakistan are still using block 52 and Saab with Adani to manufacture Gripen in India.

While being the world’s largest importer of defence equipment might be music to some of us but rest assured, India has nothing to gain by retaining the no.1 position here. India satisfies over 60% of it’s defence needs through imports, thus creating huge business opportunity. If India reduces it’s import tally by indigenously producing equipment, not only will it save quite a few million dollars but would also create thousands of jobs in the country. If India reduces it’s imports by just 20-25%, it would directly create over 1,00,000 jobs. This number is significant especially when the country is undergoing a “jobless growth” phenomenon.

Since the launch of Make in India, the government has allowed 56 manufacturing permits to private entities compared to 47 which were awarded in the preceding three years. This led to a direct decrease in the cost of defence procurement. The cost of defence procurement in 2014-15 stood at Rs.49,531 crore, down 9.96% from Rs.55,014 crore during 2013-14.

Additionally, the government has liberalized it’s licensing policy for the Indian manufacturers and also the initial validity of an industrial license has been increased from three years to 15 years with a provision to further extend it by three years on a case-by-case basis.

India has also relaxed it’s offset policy. Under the new policy, any foreign company will not have to declare the name of its Indian partner. It can set up its factory in India under new offset rules without declaring FDI and value of machines installed there. This has led to Russia partnering with India under it’s Make in India initiative with the strategic focus on two sectors:- Nuclear and defence. This partnership is just the shot in the arm that the defence industry badly needed.

India’s allocation to the defence sector in it’s annual budget generally hovers around 1.75% of the GDP. The sector employs roughly 2 lakh directly and 6 lakh people indirectly and the efficiency of defence production per person per year is Rs.15 Lakh. According to a CII-BCG report, if the current growth rate under Make in India sustains, it will end up creating an Rs 87,000 crore defence industry by the end of 2022 which would double the efficiency to Rs.30 lakh per person per year. Such damning numbers are hard to ignore and the government must ensure Make in India is successful because this will end up creating lakhs of jobs, which is just what the doctor ordered for the Indian economy.

After Nirmala Sitharaman took over as the Defence Minister from Manohar Parrikar, she is hell-bent on eradicating the bureaucratic delays is working on a proposal under which if a license remains pending over two months or after it’s due date for approval has elapsed, it will be “deemed approved” under certain cases. As of now, the ministry is working on the modalities of the proposal. Simultaneously the government is also working on tax concessions for domestic manufacturers and is als0 exploring the feasibility of making commercial the technologies developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and bring in much-needed funds through it.

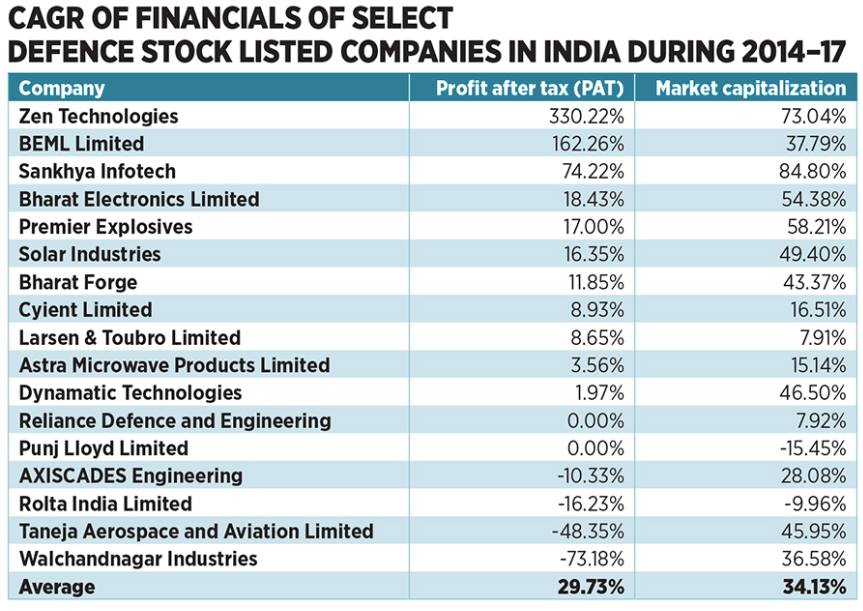

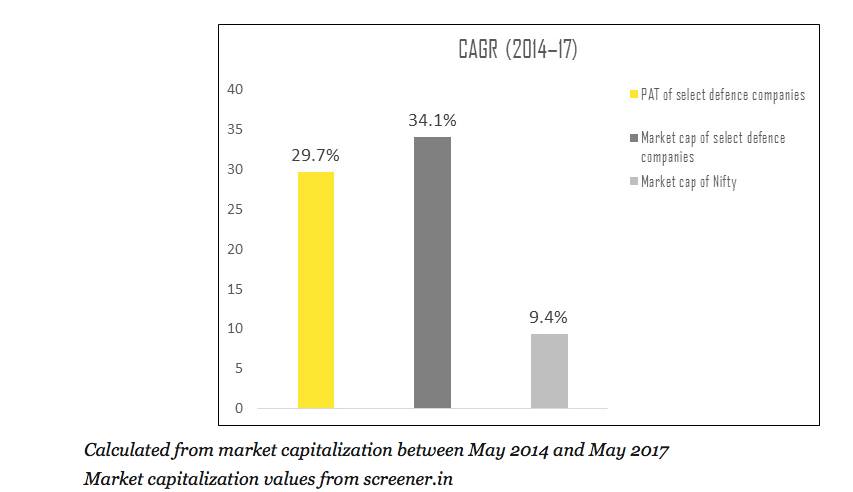

The efforts are finally bearing fruit after over three years of groundwork. The introduction of these reforms and policies has resulted in the growing market capitalization of some of the Indian defence companies have grown at a staggering outperforming Compound Annual Growth Rate(CAGR) of 34% outperforming even Nifty(=9.4%) during that period. The biggest gainer being Zen technologies which recorded a profit of 330.22% after tax and saw a market capitalization of 73.04%. On an average from 2014-17, defence companies listed in India showed a profit of 29.73% after tax and a market capitalization of 34.13%.

It is safe to conclude that the success or the failure of Make in India initiative depends on the defence industry owing to the government’s desire to produce indigenous defence equipment.

It can make or break the government. If it fails, due to the country’s poor infrastructure and red tape, there will be no place to hide for PM Modi and his Ministers as one of their flagship programmes would fail and if it succeeds, it would propel PM Modi and BJP to heights that none of them have ever reached. Things will be a lot clear come 2019, but the naysayers of Make in India are quickly running out of places to hide at.