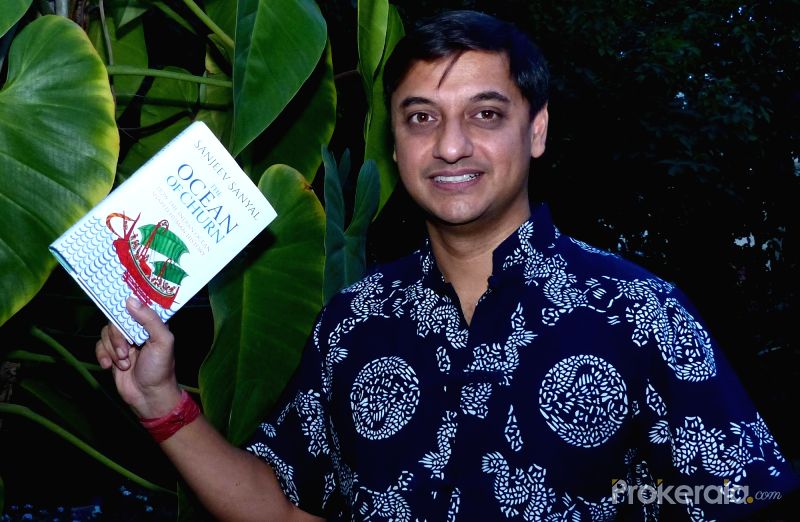

Ocean of Churn is the first time any historian in India- whether professional or amateur- has even touched upon the subject of Classical India’s maritime affairs since the legendary RC Mazumdar himself- and that alone would’ve marked it as special. But in his book, Sanjeev Sanyal has weaved together modern research, historical philosophy, logical reasoning, and pure burning love for the land and its civilization to cast an unforgettable spell upon the reader.

At the heart of Ocean of Churn lies Sanyal’s two principal arguments:-

- Why have we been ignoring Indian narratives while describing Indian history?

- Why has Indian history been always taken as monolithic dictates from Westerners or what he calls the Marxist school which considers history as an inevitable set of steps leading to ‘Communism- like some Victorian steam engine driven by the inescapable laws of Newton’?

Sanjeev Sanyal’s view of history is what he calls the Complex Adaptive System- doubtless inspired from his work in Economics- where multiple factors act upon a system to determine the direction it takes. In other words- history is a chaotic, living thing that can only be defined from the point of view of the people it involves itself- and not some predetermined mechanistic law handed down from high.

Of course, the Ocean of Churn is not an academic tome; Sanjeev Sanyal freely admits this himself in the text itself. However the sheer breadth and depth of Sanyal’s scholarship serves to take one’s breath away. Arguably since RC Mazumdar, Indian history has been treated purely as a north Indian affair centered on Delhi. Even the flagship texts of some of our eminent historians- such as the Penguin history of India- barely deign to concern themselves with ‘outlying states’ like Gujarat or Orissa or Karnataka. Neither has there been much respect for Indian points of view; Sanyal himself remarks: ‘A… systemic bias I have found in the existing literature is the preference given to writers and sources from outside the subcontinent.’

Even in his earlier works such as the Land of Seven Rivers, Sanyal has given weight to Indian depictions of their own history- but in Ocean of Churn, he truly breaks free from the shackles of the Marxist framework of Indian history, and comes into his own as a giant of modern historical writing. For arguably the first time in mainstream Indian history, he presents an unflinching critical view of Socialist icons like Ashoka and Tipu Sultan, successfully destroying the myths built around them by Marxist thinkers.

He paints a rich panorama of how Tamil, Oriya, and Sri Lankan power struggles reverberated against the length and breadth of Asia- even as far as China and Yemen. (Readers will remember how we at TFI had described Yemen’s ancient importance to India in an earlier article; even the origin of the name of the island Socotra is of Sanskrit origin) He traces the multiple migrations of peoples across land and sea to populate the continents as well as the social systems they created in response to the challenges they faced.

Sanjeev Sanyal also takes on the popular narrative of Hindus being an overly religious and superstitious people- and turns it on its head.

He describes the rich tapestry of guilds, banks, and organizations that dominated Asian trade. He describes the financial importance of temples in this system and how, as a secure holding for wealth and a source for records, they helped drive the financial systems of Indian trade. He describes the pan-Asian view of Indian kings with Tamil kings conducting marital alliances with Cambodian princesses and Oriya generals carving out rebel kingdoms in Sri Lanka.

The description of how Turkish and Arab invasions serve to destroy such fascinating cultures and systems is indeed heart-breaking. Sanyal paints the picture of this devastation in stark terms- depicting the loot of temples and the massacre of entire towns.

Unlike India’s eminent historians. Sanjeev Sanyal doesn’t shy away from calling a spade a spade; the butchery and rapine of foreign invaders is depicted as clearly and rationally as possible.

The latter part of the book is fast reading, outlining the coming of Western powers. Here Sanyal mostly focuses on the small person- and how his life was changed. Considering the amount of writing already existing on the Age of Exploration and the British Empire in India, this method does have its merits. Sanyal’s anecdotal style does have its own charm though. His description of how an Indian father’s love for his daughter helps bring down the Dutch Colonial Empire in India is as fascinating reading as it is morally uplifting. Possibly a lesson to some Common people at Delhi about how traditional Indian culture and religion can serve to fight challenges related to women’s rights?

For sake of completeness, I will not hesitate to outline some of the less impressive sections of the book. The first and most obvious is this- Sanjeev Sanyal starts out strong but as he goes on, the thread of his narrative weakens until he is just describing anecdote after anecdote. Such an affair is still informative and engaging- but it’s clear that in trying to write a book on the entire gamut of coastal India might just have been slightly good great an undertaking. The idea of history being a ‘Complex Adaptive Process’ is somewhere lost in the later parts of the book. Of course- as has already been said- Sanyal himself admits that the Ocean of Churn is not meant to be an academic tome, but the writing does appear to be excessively amateurish at a few points.

Nevertheless- this much is clear.

Sanjeev Sanyal is, quite arguably, the finest popular chronicler of Indian history active at present.

Readers of the Ocean of Churn will be faced with the image of an India- undimmed in glory and greatness, light of all Asia. They will also, in the policies of the present, be faced with the idea of a resurgent India- natural ruler of the Indian Ocean. Once Indian trade and Indian navies ruled uncontested from Vietnam to Africa. There is no reason for us to think that- with a strong government which promotes free-market trade instead of socialist fear and active militarization instead of baseless Gandhian chants of impossible utopian peace- this Classical glory cannot be achieved again.