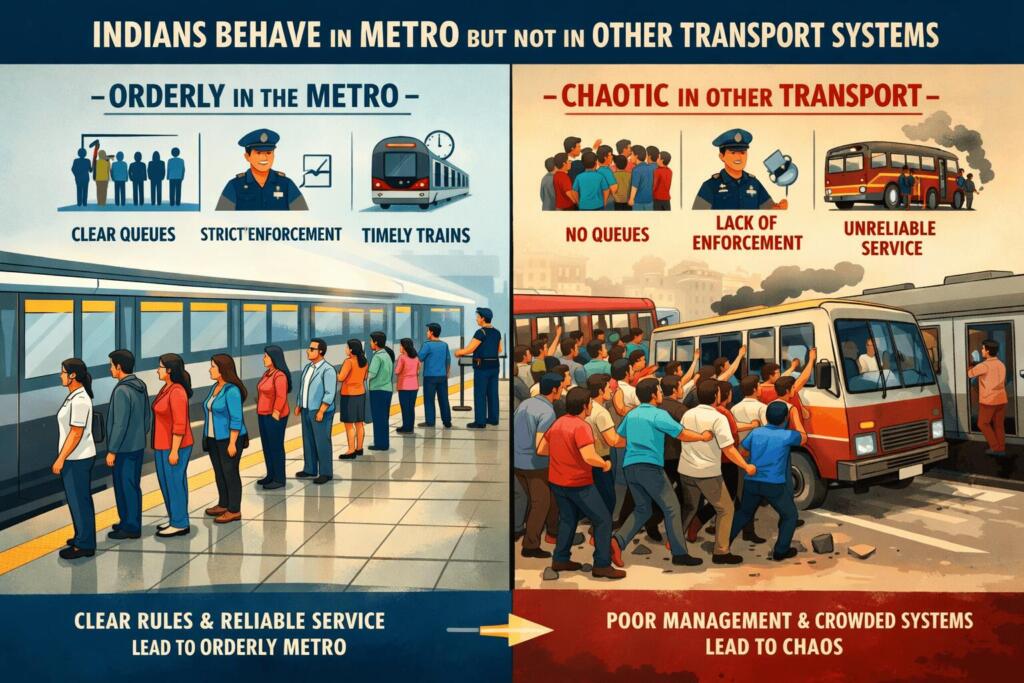

Across Indian cities, a curious pattern of commuter behaviour consistently draws notice: passengers waiting patiently and orderly in metro stations — but becoming impatient, aggressive, or chaotic in other transport systems such as buses, local trains, and roadside queueing for autos. The 2025–26 Economic Survey of India explores this contrast in depth, offering five key explanations that together provide a nuanced understanding of why people behave differently depending on the setting. In addressing this question, the survey reframes the issue not as one of individual morality, but as an outcome shaped by system design, social norms, enforcement, and expectations.

The first factor identified by the Economic Survey is clarity of rules and visible cues. In metro environments, commuters encounter clearly marked entry points, queue lines, platform screen doors, and signage that leaves little ambiguity about where to stand and how to queue. These structured cues create a predictable flow that individuals can easily follow. By contrast, in many other transport systems — whether a crowded bus stop without demarcated lines or an open suburban railway platform — such built environments are absent or poorly designed, leaving people to improvise their own systems of entry and boarding. Faced with ambiguity, commuters often resort to pushing or jostling just to secure a spot, reinforcing behaviour that appears disorderly.

Closely related is the role of enforcement. Metro stations across major Indian cities have staff, surveillance cameras, and ticketing personnel whose presence creates a consistent “shadow of authority.” Commuters understand that queue-jumping and disorderly conduct are likely to be noticed and addressed. The predictability of enforcement in metros sends a clear signal: follow the rules and queue up. In contrast, many other transport systems lack visible enforcement or rely on irregular policing. When commuters perceive enforcement as inconsistent or negotiable, adherence to norms declines, and opportunistic behaviour increases.

A third explanation offered by the Economic Survey is service reliability. One reason people are willing to wait patiently for a metro is the high frequency and predictability of metro services. Trains arrive at regular intervals, and long waits are rare. When commuters know they won’t wait long, they are less anxious and less likely to push or cut queues. But in other transport systems, irregular schedules — especially for buses in peak traffic or for intercity services with unpredictable delays — amplify commuter anxiety. This uncertainty fosters a sense that “first come, first served” is less reliable, nudging people toward rushing or squeezing ahead to secure a seat.

The survey also highlights the power of social learning and conformity in shaping behaviour. In many metro systems, orderly queuing becomes a visible social norm reinforced by commuters themselves. When individuals repeatedly see others standing in line, respecting space, and boarding in sequence, they internalise this behaviour as the expected script. This peer reinforcement — a form of self-enforced governance — makes it socially costly to behave otherwise. In less structured environments like roadside stops or open platforms, these norms are weaker or fragmented. Without widely shared expectations of orderly behaviour, individuals are less constrained by social pressure and more likely to act opportunistically, a dynamic that repeats across a range of transport systems outside the metro context.

A fifth factor identified in the Economic Survey is commuter perception of dignity and pride in the service. Metros are often seen as modern, efficient, and a source of civic pride — symbols of progress that users feel valued to be part of. This sense of ownership and respect naturally extends to behaviour: users treat the environment with care and follow the implicit rules. By contrast, many other transport systems — whether overcrowded buses, ageing suburban rail services, or informal stops — are perceived as poorly maintained or neglected. When commuters feel less invested in the dignity of the space, they are also less inclined to behave in ways that support orderliness.

Taken together, these five explanations underscore a crucial insight: behavioural differences in public spaces are less about categorically “good” or “bad” citizens and more about how environments shape expectations and actions. Where cues are clear, enforcement is consistent, reliability is high, social norms are strong, and the space is valued, orderly behaviour follows naturally. Conversely, where these factors are weaker or absent, the very same individuals may act in ways that appear disorderly or unruly.

Importantly, the Economic Survey’s findings carry broader implications for policy and urban planning. If the goal is to improve commuter behaviour across all public transport modes — not just metros — then replicating the features that encourage discipline in metro settings can be a fruitful strategy. Enhancing infrastructure to create clear queuing spaces, improving reliability of services, investing in consistent enforcement mechanisms, and elevating the public perception of other transport systems could foster more cooperative behaviour.

For example, bus depots could be redesigned with marked queue lines and sheltered waiting areas that signal expected behaviour. Suburban railway platforms could introduce better signage, crowd flow management systems, and dedicated staff during peak hours. Digital tools that provide real-time updates for bus and train arrivals could reduce commuter anxiety and impatience. Even small interventions like visual cues on the ground or public announcements reinforcing norms could strengthen the perception that orderly conduct is both expected and valuable.

Another important takeaway is the role of social norms. Behavioural change doesn’t only come from top-down enforcement; it can also be nurtured organically when individuals see and internalise desirable patterns. Public campaigns and community engagement could help build shared expectations of orderliness in non-metro settings, gradually shifting norms in spaces that currently lack them.

Indeed, the contrast between metro behaviour and other forms of public transit is not unique to India, but the Economic Survey’s framing provides a clear analytical lens that transcends anecdote. It illustrates that infrastructure and environment matter deeply in shaping civic behaviour. When people are given spaces that communicate clarity, fairness, and dignity, they are more likely to respond with cooperation and respect.

Ultimately, the question of why Indians fall in line in metros but not in other transport systems is not about a deficit of civic sense, but about the conditions that either enable or hinder its expression. By addressing these conditions thoughtfully, urban planners and policymakers can help extend the culture of order and predictability seen in metros across the full spectrum of India’s public transportation landscape — making daily commutes smoother, safer, and more equitable for all.