In a deeply unsettling incident, three minor sisters, aged 12, 14 and 16 died by suicide early Wednesday morning in UP’s Ghaziabad after allegedly jumping from the ninth floor of their residential building.

As per reports, the incident took place around 2 am at Flat No. 907 in B-1 Tower in Ghaziabad’s Bharat City society.

According to initial information, the girls identified as Vishika (16), Prachi (14), and Pakhi (12) spent an significant time on mobile phones and were suspected to be addicted to a task-based Korean gaming application, to which their parents objected.

The task/challenge based ‘Korean Love Game’ called ‘We are not Indians’ reportedly has a 50th ‘challenge’ which is to commit suicide. Initial findings suggest that the girls used a two-step ladder to climb over the balcony as part of the game’s final task.

The noise from the inicident was loud enough to awaken several residents of the complex, prompting neighbours and security personnel to rush to locate its source.

However, by the time the girls’ family members forced open the room, all three had already jumped. The girls were rushed to a hospital in Loni, where they were declared dead, police said.

The police reached the scene, began conducting preliminary inquiries and sent the bodies for a post-mortem examination. Currently, investigators are questioning family members and neighbours to establish the sequence of events.

According to police, the victims’ diaries revealed a deep appreciation for Korean culture. The girls wrote that they loved Korean culture and various forms of Korean entertainment such as Korean movies, music, short films, shows and series.

Ghaziabad Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP), Nimish Patil told ANI, “In the early hours of 4th February, we received information that three girls jumped from a building. They were declared dead at the hospital. We have found a suicide note in the case. From the suicide note, it is clear that the three girls were influenced by Korean culture. No particular app was named. At the time of the incident, the whole family was present in the house, but they were sleeping.”

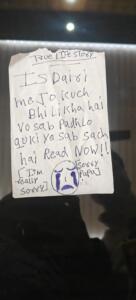

The Sisters’ Death Note

Before taking their lives, the three girls left behind an eight-page note in a pocket diary, in which they apologised to their parents and described their gaming activities.

Written in a mix of Hindi and English, the note urged their parents to read the diary in full, stressing that everything written in it was true.

“Is diary me jo kuch bhi likha hai vo sab padh lo quki ye sab sach hai. (Read everything written in this diary because it’s the truth). Read now! I’m really sorry. Sorry, Papa,” the note stated.

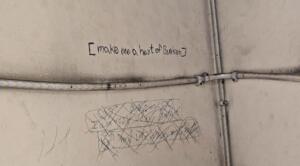

The message was followed by a large crying emoji. Additionally, one of the girls had written on a wall in their room, “I am very, very alone, my life is very very alone.”

What was the Korean Love Game?

The girls were reportedly addicted to this online, task-based Korean game during the Covid pandemic. The note left behind indicated that their fixation ran so deep that they had adopted Korean names for themselves and carried out tasks assigned within the game.

This ‘game’ typically begins when an unknown person contacts a child via social media or certain mobile apps. The individual claims to be Korean or at least a foreign national and speaks to the child about friendship and love. Once a degree of trust is established, the child is assigned tasks, starting with simple challenges, such as waking up in the middle of the night, stated reports.

Over time, the tasks reportedly become more difficult, with the ‘game master’ threatening children who fail to comply. The challenges are said to continue for 50 consecutive days, with the final task allegedly being suicide.

The father reportedly confirmed that his daughters had begun referring to themselves by Korean names. When the parents attempted to intervene, including restricting mobile phone usage, the sisters allegedly said, “… Korea is our life, Korea is our biggest love, whatever you say, we cannot give it up …”

The House They Left Behind

Police also found photos of the family members scattered on the floor of the victims’ room following the incident. Scribbles on the wall inside the building were found that read, “I am very, very alone. My life is very, very alone.”

Preliminary investigation reveals that the girls did not attend school over the past two years and have been staying at home, allegedly due to weak academic performance and financial issues, said DCP Nimish Patil.

For the past few days, the family had also imposed restrictions on their use of mobile phones, he said, adding that the exact reason behind the triple suicide is still under investigation.

Chetan Kumar, the father of the victims, said he was unaware of his daughters playing what he initially called an “online task-based game,” otherwise, he wouldn’t have allowed them to play it.

“Whatever happened is terrible. I hope this never happens to another child. I urge parents to not let their children play video games. I didn’t know about this game. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have let them play,” he said reportedly.

Notably, Kumar has been was married twice. He first married a woman who was not able to conceive initially and then married the woman’s younger sister, with whom he had three children. Later, the first wife had two children.

Among the three victims who died by suicide, two were daughters from the man’s second marriage, while the third was his daughter from his first marriage. The two surviving children are – a boy who is 9-years-old and a girl, 3.

Questions that Linger Over the Tragedy

As the investigation into the girls’ digital lives and family interactions continues, the case raises troubling questions about youth mental health, the adequacy of parental guidance, online pressures, and the silent burdens children may carry in their homes.

The deaths of the three girls highlight the vulnerabilities of young minds in the digital age, where online platforms can exert a powerful influence over impressionable adolescents.

The girls’ obsession with a task-based Korean game reflects how unchecked digital exposure, combined with emotional isolation, can steer children toward harmful behaviour. The case also raises serious questions about parental supervision and negligence, why were the girls left unsupervised for long periods? Why were they unable to attend school, even though affordable options existed? How did foreign applications with dark and manipulative content gain such sway over them?

The notes and diaries left behind reveal a deep fascination with Korean culture, yet they also expose loneliness, emotional distress, and a cry for connection that seemingly went unheard at home.

This incident forces society to reflect on the balance between freedom and oversight in children’s lives, the importance of open communication, and the urgent need for parents to actively monitor and guide their children’s online and offline worlds.

Free, Accessible, Fatal: Threat of Dangerous Online Games

Many online games with dark, manipulative content have tragically led to the deaths of young and naive children, often exploiting their curiosity, loneliness, or vulnerability.

The phenomenon gained global attention with the ‘Blue Whale Challenge,’ believed to have originated in Russia, in which a curator assigned players a series of increasingly dangerous tasks over 50 days, culminating in suicide.

The game preyed on children through threats, blackmail, and psychological manipulation, with its name inspired by blue whales, which are known to intentionally beach themselves. India saw its first reported case in Mumbai, and as recently as 2024, a 15-year-old boy in Pune, who had become isolated and addicted to online games, jumped from a 14th-floor building.

Similarly, the ‘Momo Challenge’ in 2018 involved children being coaxed into adding unknown contacts on WhatsApp and completing escalating tasks that eventually led to suicidal acts, including the death of a 12-year-old girl in Argentina.

These and many other such games are freely accessible online, often disguised as harmless or entertaining, yet they desensitize young minds to violence and manipulate children’s emotions, creating global threats to adolescent safety and mental health.