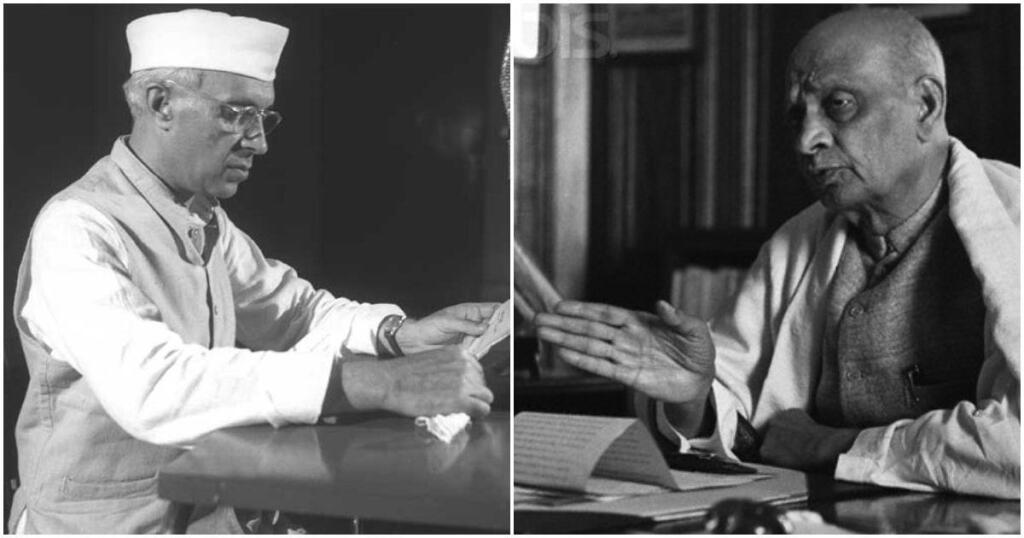

History often reveals its most significant truths not through sweeping proclamations but through quiet entries in personal diaries. One such revelation appears in Inside Story of Sardar Patel: The Diary of Maniben Patel (1936–1950), a primary source that records private political conversations at the highest levels of India’s early leadership. The crux of the matter is that according to Maniben’s diary, Jawaharlal Nehru raised the idea of rebuilding the Babri Masjid using government funds, and Sardar Patel firmly declined. The passage forms part of Maniben Patel’s detailed notes, which in turn have been reproduced in a published historical document. The significance lies not in political sensationalism but in what these notes reveal about the differing philosophies of two central figures during India’s formative years.

Maniben’s diary entry describes a conversation dated September 20, 1950. In it, Maniben records that Nehru brought up the Babri Masjid issue with Patel, evidently expecting that the government could take up the project and allocate public money toward the reconstruction of the mosque. Patel, however, responded unequivocally that public funds could not be used for the construction of any place of worship. This direct exchange, as recorded by Maniben, captures a moment in which two divergent approaches to public policy surfaced. Patel’s reply reflected a firm commitment to the neutrality of the state in religious matters, insisting that government expenditure must not be directed toward such projects.

The crux of this historical note becomes even sharper when considered alongside her diary mention of the Somnath Temple restoration. Maniben’s diary records Patel explaining to Nehru that the Somnath reconstruction effort was not funded by government money at all. Rather, it was being carried out by a public trust created specifically for that purpose. According to her account, Patel informed Nehru that nearly thirty lakh rupees had already been raised through voluntary contributions, and that a formal trust structure had been created with a chairman and members, including K M Munshi. The government, therefore, bore no financial burden in the project. Patel’s explanation effectively closed the discussion, at least as her diary presents it.

The importance of these entries does not lie in pitting historical figures against one another but in understanding the nuanced choices and differing ideologies within India’s early leadership. Maniben’s documentation portrays Patel as deeply focused on restoring stability and ensuring clear governance principles after the traumatic upheaval of Partition. Maniben’s diary repeatedly shows him emphasising administrative discipline, national unity and institutional clarity. In contrast, Nehru’s political instincts, as reflected in this specific entry, appear inclined toward projects he believed could contribute to communal harmony, even if those projects risked crossing into areas involving state participation in religious affairs.

Maniben’s diaryn entry becomes especially striking when placed within the broader context of the period in which it was written. In 1950, India was still recovering from massive displacement, communal tensions and constitutional reorganisation. Every decision at the central level had deep implications not only for governance but also for the symbolic direction of the new republic. The question of whether government funds should ever be used for religious reconstruction was not merely a technical debate. It was a philosophical one that would shape the nation’s identity. Patel’s refusal, as recorded by Maniben, therefore highlights a stance that sought an unambiguous separation between state authority and religious restoration.

Another central aspect of the crux is that these details come directly from a primary personal diary maintained by Patel’s daughter. They are not retrospective claims or political reinterpretations but contemporaneous notes written by someone who regularly observed these leaders’ work and conversations. Diaries are, of course, subjective documents. Yet they remain invaluable for understanding the tone and nature of private political interactions that are not always reflected in official records. When such diaries are published, they provide insight into what senior leaders discussed behind closed doors and how they navigated their disagreements.

The fact that this particular entry appears in a published historical document means it forms part of the scholarly conversation about independent India’s early leadership. The text highlights patterns that historians have long studied: the contrast between Nehru’s diplomacy-driven political instincts and Patel’s administrative pragmatism. It does not, however, demand that readers adopt a partisan stance. Rather, it invites them to consider how two leaders approached governance differently and how those differences influenced policy debates during India’s earliest years of self-rule.

The resurfacing of such entries is a reminder that historical narratives are often shaped by what is emphasised and what is left unspoken. Over the decades, public memory has tended to depict Nehru and Patel as a cohesive national leadership, united in shared goals. While they certainly collaborated on major decisions, primary sources like Maniben’s diary show that they also disagreed on many matters of principle. These disagreements were neither small nor inconsequential. They form an important part of understanding how India’s political and administrative foundations were built.

In examining this diary entry, the most responsible approach is to take it for what it is: a personal record by a contemporary observer, offering insight into a conversation between two foundational leaders. It does not need embellishment, and it does not require reinterpretation. It merely requires attention as a historical source. If anything, it encourages readers to revisit the complex interplay of ideas, priorities and philosophies that shaped early independent India.

Ultimately, the crux remains clear. According to Maniben’s diary, Nehru proposed that public funds be used for rebuilding the Babri Masjid, and Patel rejected the idea, insisting on the principle that government money must not support such religious projects. This moment, preserved in writing, invites renewed reflection on how India’s early leaders understood the relationship between state authority and religious life. It also illustrates the enduring value of primary sources in uncovering the layered truths of history, truths that sometimes remain dormant until readers are willing to confront them anew.