In the rugged landscapes of Pakistan, sacred remnants of Hindu spirituality still thrive, drawing pilgrims from across the region despite the country’s Muslim-majority identity. Among them, the Hinglaj Mata temple in Baluchistan and the Sharda Peeth in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir stand as ancient Shakti Peethas places where parts of Goddess Sati’s body are believed to have fallen, sanctifying the land forever. These sites, steeped in mythology, history, and devotion, continue to anchor Hindu traditions in a land where the community now makes up just 2.14% of the population.

The legend of the Shakti Peethas, originating from the tragic self-immolation of Sati and the grief-stricken wanderings of Lord Shiva, ties together dozens of temples across South Asia. In Pakistan alone, three such revered shrines Hinglaj Mata, Sharda Peeth, and Shivaharkaray remind the faithful of their enduring roots.

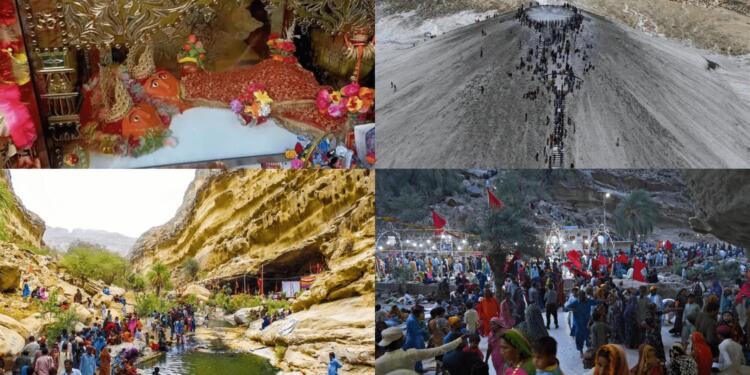

Hinglaj Mata: The Sacred Cave in Baluchistan

The most famous Shakti Peeth in Pakistan, Hinglaj Mata, is located inside Hingol National Park in Baluchistan. Known also as Hinglaj Devi, Hingula Devi, or Nani Mandir, this cave temple is one of the most important pilgrimage destinations for Hindus in Pakistan. According to mythology, it marks the spot where Sati’s Brahmarandhra (part of the head) fell. Ancient texts like Tantrachudamani reference this site as Hingula, with Devi named Kottari and her associated Bhairava called Bhimalochana.

Every spring, Hinglaj Mata hosts one of the largest Hindu festivals in Pakistan the Hinglaj Yatra. More than 100,000 pilgrims travel, often from Sindh, Hyderabad, and Karachi, to participate. The journey itself is arduous: buses carry devotees across the Makran Coastal Highway, after which they must trek barefoot across parched terrain, windswept deserts, and rocky paths to reach the shrine.

At the temple, pilgrims climb steep mud volcanoes, ascend hundreds of stairs, and perform rituals by tossing coconuts and rose petals into shallow craters, seeking the goddess’s blessing. The chants of “Jai Mata Di” and “Jai Shiv Shankar” echo against the stark, arid landscape, reflecting the resilience of faith in the face of harsh geography. Despite political and social challenges, Hinglaj Mata remains a focal point of spiritual unity and devotion for Hindus in Pakistan and the wider diaspora.

The Legend Behind the Shakti Peethas

The story of Hinglaj Mata and Sharda Peeth is rooted in the epic tale of Sati and Shiva. As per the Shiva Purana, Sati, humiliated by her father Daksha’s refusal to invite Lord Shiva to a yajna, immolated herself in anger and despair. A grief-stricken Shiva wandered the cosmos with her body. To calm him and restore balance, Lord Vishnu dismembered Sati’s body with his Sudarshan Chakra, scattering her remains across the earth. Each place where a part fell became a Shakti Peeth, sanctified forever as an abode of the Goddess.

Over centuries, the list of Shakti Peethas has grown, with traditions citing 51 or 108 sites across the subcontinent. In Pakistan, Hinglaj Mata and Sharda Peeth hold particular reverence. These shrines not only embody the mythological significance of Sati’s sacrifice but also symbolize the deep cultural and spiritual ties that bind the Indian subcontinent beyond political borders.

Sharda Peeth: The Forgotten Seat of Learning

Far from Baluchistan, in the Neelum Valley of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, lies Sharda Peeth a ruined but historically illustrious temple. Believed to mark the spot where Sati’s right hand fell, Sharda Peeth is more than a religious site; it was once a thriving centre of learning between the 6th and 12th centuries CE. Its library drew scholars from across Asia, making it one of the foremost intellectual hubs of the time.

The temple played a key role in developing the Sharada script, from which Kashmir earned the name “Sharada Desh,” meaning “the country of Sharada.” For Kashmiri Pandits, Sharda Peeth, along with the Amarnath Temple and Martand Sun Temple, remains among the three holiest sites for pilgrimage.

Perched 1,981 metres above sea level along the Neelum River and just 10 km from the Line of Control, Sharda Peeth today lies in ruins but continues to evoke reverence. For many Hindus, especially displaced Kashmiri Pandits, it is not only a Shakti Peeth but also a poignant reminder of their cultural roots across the border.

Faith Amidst Adversity in Pakistan

Despite forming a small minority of 4.4 million people in Pakistan, Hindus continue to nurture their traditions through pilgrimages to these Shakti Peethas. The Hinglaj Yatra, in particular, stands as a symbol of resilience. Pilgrims, braving dust storms, desert heat, and long treks, reaffirm their faith with each visit. The temple’s senior priest, Maharaj Gopal, describes Hinglaj Mata as “the most sacred pilgrimage in the Hindu religion,” promising forgiveness of sins for those who worship during the three-day rituals.

Yet, accessibility remains a challenge. Pilgrims face limited vehicular access, often carrying children and belongings on foot over difficult terrain. Still, the journey is viewed not as an obstacle but as part of the spiritual discipline required to approach the goddess.

For Sharda Peeth, however, the obstacles are not physical but political. Located in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, access for Indian Hindus remains barred due to geopolitical tensions. This restricted access has made Sharda Peeth a symbol of longing for Kashmiri Pandits and other Hindus who wish to reconnect with their heritage.

Sacred Ties Beyond Borders

The Shakti Peethas of Hinglaj Mata and Sharda Peeth highlight the enduring presence of Hinduism in Pakistan, offering a glimpse into the deep spiritual geography of the subcontinent. Hinglaj Mata thrives as a living centre of worship, while Sharda Peeth stands as a haunting reminder of a glorious past as both a temple and a seat of knowledge.

Despite Pakistan’s small Hindu population and the challenges of worship in a Muslim-majority nation, these sacred sites remain powerful symbols of faith and resilience. They remind the world that spirituality transcends political boundaries, and that the cultural heritage of the subcontinent continues to endure, carried by pilgrims who keep the flame of devotion alive against all odds.