USAID funding scandal: In the last part of our series on Deep State, we explained the role of key persons and organisations running a seamless ‘scheme’ against the free world as well as their modus operandi. This part particularly focuses on how the deep state has weaponised the civil society and NGOs to further its vested political interests around the world.

USAID’s funding of NGOs and civil society groups has long been presented as a tool for promoting democracy and human rights. However, beneath this facade lies a well-documented pattern of using these organizations to influence foreign governments, manipulate public sentiment, and fuel unrest to serve American strategic interests. From Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan Revolution to Venezuela’s opposition movements and Bangladesh’s destabilization attempts, USAID has played a crucial role in engineering political disruptions across the globe. This article delves into the deep state’s use of civil society as a weapon for economic and political coercion.

NGOs and Civil Society

The U.S. government has funded truckloads of NGOs and civil society organisations to promote the interests of the military-industrial complex. These organisations often operate under the guise of promoting democracy and human rights, but beneath that, they tend to influence foreign governments and societies in ways that align with U.S. interests.

One of the most well-documented examples is Ukraine, where USAID and its affiliated NGOs played a deciding role in the 2014 Maidan Revolution. Victoria Nuland, then Assistant Secretary of State, had absolutely no shame in publicly accepting that the U.S. had invested over $5 billion in Ukrainian civil society groups through USAID and NED.

NGOs such as the George Soros-founded International Renaissance Foundation, Ukraine’s largest charity organisation, is funded by USAID and Soros’ Open Society Foundations, actively supporting opposition protests, training activists, and providing financial support to fuel revolts and discontent.

The Center for Civil Liberties, another USAID-funded group, played a role in organising street-level protests that provided feeder services to nationwide movements and ultimately led to the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych.

In Bangladesh, USAID and IRI devised a plan to destabilise the government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, funding 170 opposition activists, 304 key informants, and multiple civil society organisations to create an Islamist-led anarchy in the country.

The agency identified ethnic minorities, LGBTQ communities, and amenable youth as crucial for mass mobilisation, using rap music to spark nationwide protests. This effort led to widespread unrest and violent clashes.

Venezuela has been a major target of USAID-backed NGOs, particularly under the administrations of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro.

Maduro himself revealed that USAID has provided over $700 million in funding to organisations proclaiming their loyalty to Juan Guaidó, former acting president and opposition leader of Venezuela. “260 million [dollars] for supposed humanitarian assistance, 247 for development, 200 million from a fund they called development fund… In the documents, they are more than 700 million.” To this end, the US government, Maduro claims, withdrew funding from the UN or UN-subsidised organisations to give it “to whomever Juan Guaidó ordered.” said Maduro.

The Venezuelan Institute of Press and Society (IPYS Venezuela) and Espacio Público—both heavily funded by USAID—have played a key role in promoting anti-government narratives.

Documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) revealed that funds were channelled through intermediaries like the Pan American Development Foundation (PADF) to secretly support groups aligned with opposition parties.

Espacio Público, a Venezuelan NGO claiming to be independent, received undisclosed subgrants from PADF, funded by the U.S. State Department. It frequently tried to implicate Chávez’s government over alleged violations of press freedom – the same modus operandi which is followed in India.

Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPyS-Ve), the Venezuelan chapter of a Peru-based journalism group, was also funded by USAID and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). It received PADF subgrants and actively accused Chávez of suppressing press freedom.

In the mid-2000s, USAID funnelled millions of dollars to Venezuelan NGOs through Development Alternatives Inc. (DAI). After exposure, USAID switched to using PADF, which has close ties to the Organization of American States (OAS), to continue funding opposition media and civil society groups. PADF facilitated grants and training programs for Venezuelan journalists who tended towards targeting elected governments through narrative warfare.

It provided investigative journalism grants and sponsored courses in four Venezuelan universities while collaborating with Espacio Público and IPyS-Ve. PADF also funded internet-based and investigative reporting training, offering 10 one-year journalism grants of $25,000 each, a significant sum in Latin America.

The NED also finances groups like Súmate, which played an instrumental role in the organisation of protests against Chávez and Maduro. USAID-backed efforts reached their zenith in 2019, when opposition leader Juan Guaidó declared himself interim president with the support of the United States, after decades of manufactured agitation by heavily funded civil society groups.

In 2012, the Vladimir Putin-led Russian administration threw USAID out of its territory for its role in attempting to influence democratic political processes, particularly elections and their results. The now-tainted organisation had been operating in Russia for more than two decades and had invested approximately $2.7 billion in various projects – $50 million of which was invested in 2012 itself.

The massive funding supported anti-government organisations such as Golos, Memorial, and Transparency International Russia, among others. On the face of it, these organisations claimed to be focused on election monitoring, human rights, and anti-corruption agendas. However, Russian agencies found that these groups were acting as foreign agents promoting the interests of the US and its allies, which ultimately led to harsh but direct measures against these and 54 other NGOs receiving funding from organisations outside Russian borders.

In Eastern Europe, “Colour Revolutions” – most notably Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution and Kyrgyzstan’s 2005 Tulip Revolution, are also alleged to have deep involvement from the American deep state. USAID, NED, and the Open Society Foundations (OSF) have been reported to join hands and support anti-national civil society groups in these regions.

In Georgia, the playbook of inciting youth was repeated, leading to the youth movement Kmara playing a decisive role in the Rose Revolution, resulting in the resignation of President Eduard Shevardnadze. Reports suggest that OSF, founded by George Soros, provided financial assistance to NGOs and opposition parties within Georgia. USAID, for instance, spent $1.5 million to computerise Georgia’s voter rolls as it believed that non-computerisation helped the deep state’s enemies.

Similarly, in Kyrgyzstan, the Coalition for Democracy and Civil Society played its role as the leader of civil society during the Tulip Revolution, which led to the ouster of President Askar Akayev. The US is said to have assisted it in receiving funding from donors with cross-border connections. On the face of it, the money was utilised for election monitoring and voter education, but the final result itself shows that all these efforts were directed towards mass mobilisation.

The US supported Kyrgyzstan’s opposition by providing financial assistance to NGOs and opposition parties, which eventually turned into riots leading to the President abandoning power and fleeing.

The Asian Development Bank noted that the ruckus originated in the 1990s, when the development of the NGO sector in Kyrgyzstan was supported by international donors who facilitated the active establishment of NGOs.

In Latin America, USAID has supported opposition media and civil society groups in Nicaragua, Bolivia, and Cuba.

In Nicaragua, USAID’s efforts have been channelled towards undermining the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) led by Daniel Ortega.

During the 1980s, the Ronald Reagan administration provided $100 million in military aid to the Contras, a banned right-wing rebel group fighting the Sandinista government. The CIA and figures like Oliver North were instrumental in covertly funnelling funds through the Iran-Contra affair, where proceeds from illegal arms sales to Iran were redirected to support the rebels.

After the electoral defeat of Ortega in 1990, USAID primarily put emphasis on strengthening neoliberal governance under Violeta Chamorro and funded opposition political movements like the Constitutionalist Liberal Party (PLC) and media outlets which chose to criticise Sandinistas.

Over the years, U.S. funding continued to flow into civil society organisations and political opposition under the pretext of democracy promotion.

But Ortega did not give up, and he returned to power in 2007, forcing USAID to intensify efforts to destabilise his government. However, the deep state failed miserably but continues its endeavour to this date.

Between 2017 and 2021, USAID allocated over $31 million to Nicaraguan opposition groups such as Citizens for Liberty (CxL), Blue and White National Unity (UNAB), and the Civil Alliance for Justice and Democracy.

These funds were channelled towards supporting anti-government protests in 2018, which the Ortega administration labelled as an attempted coup. The Trump and Biden administrations expanded sanctions – the financial version of cancel culture – and cut Nicaragua’s access to international financial institutions, putting Ortega under pressure.

The NED also played a key role in channelling U.S. funds to opposition media and NGOs. Ortega’s government has repeatedly condemned U.S. interference and had to resort to expelling organisations linked to foreign funding and tightening restrictions on external influence in Nicaraguan politics.

In Bolivia, USAID’s involvement in funding opposition groups played a role in the 2019 ousting of Evo Morales, as civil society organisations it supported helped create the conditions for his removal.

In Cuba, the USA has cherished the dream of destabilising the Cuban government since the Cuban Revolution in 1959.

In 2020 alone, NED allocated more than $5 million to various organisations working to undermine Cuba’s political system. These funds supported groups such as the Cuban Democratic Directorate ($650,000), the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs ($500,000), and the Center for International Private Enterprise ($309,766), among others.

The stated goal, of course, was to promote so-called democratic values while actions were aligned with direct infringement of Cuba’s sovereignty. Carl Gershman, the NED president, and USAID administrator Mark Green, who collaborated with U.S. lawmakers like Democratic Senator Bob Menéndez and Republican Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen—both known for their strong anti-Cuba stance—are some of the key American villains in this battle.

The monstrosity reached such a level that during the COVID-19 pandemic—when people were dying—Americans saw it as an opportunity to tighten the blockade and strain the Cuban economy, which could turn into internal dissent metamorphosing into a full-fledged civil war.

To enable social media for anti-government mobilisation, the U.S. had also sought to launch ZunZuneo, a secret social media platform designed to undermine the Cuban government way back in the late 2000s. To conceal American dollars’ involvement, it operated through a complex web of front companies, including MovilChat in the Cayman Islands. Initially, the platform was partially successful too, as at its peak, it had over 40,000 unsuspecting Cuban users unaware of the fact that it was a U.S. government project collecting their private data.

From the U.S. government, Joe McSpedon of USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives—a hassle-free division created after the fall of the Soviet Union to promote U.S. interests in quickly changing political environments—led the effort. Contractors like Creative Associates International and Mobile Accord, along with a Cuban engineer based in Spain, were other key nodes in this operation.

Despite its scale and ambition, ZunZuneo collapsed by 2012 when funding ran out, and the Cuban government began to block the service. But its death did not go without highlighting the sickening lengths to which the U.S. was willing to go to infiltrate Cuban society under the guise of promoting free speech.

Africa—probably still stuck in colonialist legacy—has also seen extensive USAID-backed civil society activities aimed at influencing political positions on the continent.

In Sudan, USAID funded various groups, allocating $50 million to what it terms democracy and governance programs. In 2019, the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), a coalition of doctors, lawyers, and engineers, spearheaded the demonstrations against Omar al-Bashir, leading to his ouster.

While there is no direct evidence that USAID financed or coordinated with the group, USAID’s extensive involvement in supporting transitional governance structures and funding organisations claiming to work on democratic reforms indicates something could be fishy. These activities cannot be separated from the broader push for regime change—an initiative for which the organisation is infamous.

Even in Zimbabwe, that scepticism travels. USAID has funnelled millions into Zimbabwe’s civil society, backing groups like the Crisis in Zimbabwe Coalition under the guise of promoting democracy, human rights, and election monitoring—the old tropes used to do exactly the opposite of what these words convey. They claim to ensure transparency, but their frequent clashes with the ruling ZANU-PF party suggest a more politically charged agenda.

During the 2018 elections, USAID-funded observers reported irregularities that directly conflicted with the government’s claims of fairness, reinforcing scepticism about USAID’s neutrality. These allegations are generally the first step in the long game of undermining public confidence in the ruling government.

In Afghanistan, USAID’s work with civil society was closely linked to the U.S. military strategy. USAID has been actively involved in Afghanistan, funding over 200 NGOs to promote governance, gender equality, and human rights. From 2015 to 2018, USAID’s women empowerment programs served over 61,000 women, providing leadership skills, business development services, and civil service training.

Additionally, USAID enabled women-owned enterprises to receive nearly 50,000 loans totalling $10.1 million, supporting economic opportunities for Afghan women. While these are worthy goals to achieve, they clashed with local Taliban fighters, who were on the back foot but only militarily. USAID took this mission not as part of an initiative to improve Afghan women’s lives but as a shield that would help other European powers engaged in the American war against the Taliban.

USAID’s involvement in judicial reform through NGOs has also played a role in legal battles targeting political opponents. USAID has invested heavily in judicial reforms across Latin America and Central Asia, funding projects aimed at enhancing legal transparency, accountability, and efficiency.

In Colombia, millions of dollars were allocated to the Justice for a Sustainable Peace program, strengthening judicial institutions and access to justice in rural areas. The exact details were not available, but given that $413 million was planned funding in Colombia for 2025, a minimum of $50 million to penetrate the judiciary is not a far-fetched assumption.

In Guatemala, USAID has supported judicial administrative reforms and has come up with anti-corruption efforts, including a $12.3 million program to improve financial management systems. Similarly, in Honduras, USAID has tinkered with the process of selection of the attorney general under the guise of reinforcing the rule of law. In El Salvador, a five-year program managed by Dexis Consulting Group has been pushed to strengthen citizen participation in legal processes. The country received $35 million for it.

In Ethiopia, the 2019-launched Feteh (Justice) Project was designed to provide rapid-response technical assistance to judicial institutions for modernising legal frameworks and expanding access to legal aid. In Serbia, the Judicial Reform and Government Accountability Project has focused on improving transparency and efficiency, particularly in misdemeanour and administrative courts.

Coming to Central Asia, Uzbekistan’s Legal Reform Program has aimed at legislative improvements, legal education, and gender equality. One of its neighbours, Kazakhstan, launched its Rule of Law program in 2020 to enhance judicial accountability and support anti-corruption initiatives. In Kyrgyzstan, the “Ukuk Bulagy” Project has been working to create a more responsive and impartial justice system using a people-centric approach.

All of these initiatives sound worthy of it. For instance, the program in El Salvador is advertised as one that will encourage ‘citizen participation’. There is a similar term used by American agencies—especially USAID—for their interference in governance, and that term is ‘voter participation’.

This is nothing but a cloak for programs whose functionaries go to places and speak with venom against the democratically elected government. In the same way, these programs are used to create a system of advocates, judges, and prosecutors whose ultimate purpose is destabilising society. There is now a proper term called “Soros-backed Prosecutors and Judges” for it.

Generally, these legal professionals use phrases like ‘liberal democracy, social justice, secular republic, humanity, brotherhood, sisterhood, gendered language, stigmatised virtue’ to pardon the gravest of criminals who come out and commit the same crime again. The cycle continues, and judges continue to favour them until a counterforce is built there.

These legal professionals have their own political allegiance and read as well as interpret laws accordingly. They decide punishment based on gender, race, caste, colour, and, of course, religion. A rapist from a particular community may get pardoned, while a truth-teller from another community will be rebuked in open courts.

Also Read: This Week in Focus: The Deep State Playbook Part 3 – Economic Coercion

While how much Soros and USAID have penetrated other countries’ judicial systems is still something not clear, the devastation of American civil lives can be traced back to his involvement. In a decade, Soros spent at least $5 million to appoint his own prosecutors, who hobnob with criminal elements in the name of social justice and humanity.

He funded more than 70 prosecutors in America, leading to a spike in anti-social activities like theft, dacoity, and murder, among others. A book named Rogue Prosecutors: How Radical Soros Lawyers Are Destroying America’s Communities, written by authors Zack Smith and Charles D. Stimson, has described this phenomenon in detail.

If this is the damage Soros and USAID can cause to the most powerful country in the world, imagine what the impact will be on smaller ones—and that includes Europe too.

Psychological Operations

Psychological Operations (PSYOP) across various military engagements to influence adversaries and achieve strategic objectives is another way in which the American Deep State functions.

During the Vietnam War, the Joint U.S. Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO) tried to influence the opinion of the Vietnamese public and minimise local ground support for Vietnamese units deployed against it.

Under Operation Wandering Soul, the USA started to manipulate Vietnamese cultural and spiritual beliefs, particularly the fear of restless spirits resulting from improper burials. They created recordings of eerie sounds, Buddhist funeral music, and distorted voices mimicking deceased Viet Cong soldiers. These voices were shown as tormented spirits, and in a very painful tone, they pleaded with their living comrades to abandon the fight and return home to avoid a similar fate.

One of the most infamous recordings, Ghost Tape Number Ten, was broadcast from helicopters and ground units during nighttime operations. The unsettling audio was intended to instil fear, disrupt enemy rest, and create psychological vulnerability among Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops.

The Chieu Hoi (“Open Arms”) Program aimed to persuade enemy soldiers to defect. It deployed a combination of propaganda, incentives, and assurances of safety. Propaganda leaflets and radio broadcasts emphasised the benefits of surrendering, while safe conduct passes—often printed on waterproof materials like ammunition bags—were distributed widely to guarantee safe passage for defectors.

Varied sources estimate that by 1967, the programme had recorded approximately 75,000 defections, though analysts estimate that only about 25 per cent of these were genuine. Its effectiveness was limited by factors such as fear of communist reprisals and cultural misunderstandings in the propaganda materials.

Despite these challenges, the Chieu Hoi Program was considered largely successful due to reports of removing over 100,000 combatants from the battlefield, many of whom even defected towards the Americans. Many defectors, known as Hoi Chanh, were reintegrated into allied forces as Kit Carson Scouts, where they provided valuable intelligence and operational support. Some even received military commendations, such as the Silver Star, for their contributions to U.S. efforts.

In Panama during Operation JUST CAUSE in 1989, U.S. forces developed the “Ma Bell Mission”, formally known as capitulation missions, to ensure that Panamanian strongpoints surrendered even without the use of combat techniques. Special Forces teams who spoke fluent Spanish were attached to combat units and used telephone access to contact Panamanian commanders.

Panamanian commanders were asked to surrender and bring troops to assemble unarmed on parade grounds or face lethal consequences. The trick, which relied heavily on phone communication and language fluency, was instrumental in securing 14 strongpoints, the surrender of nearly 2,000 troops, and the capture of over 6,000 weapons—all without U.S. casualties. Several high-ranking associates of Manuel Noriega on the “most wanted” list were also captured through these operations.

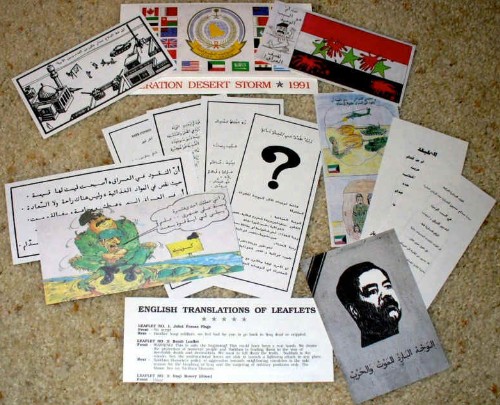

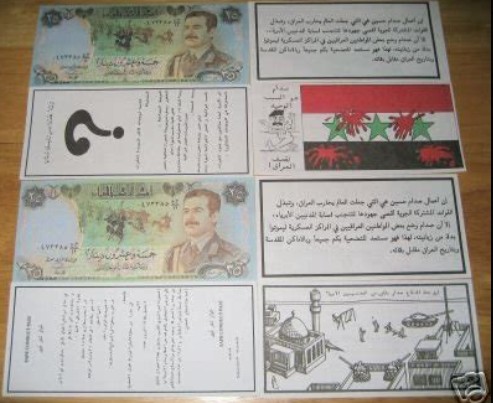

During the Gulf War in Operation DESERT STORM, PSYOP units used leaflets and radio broadcasts to demoralise Iraqi soldiers and bring them to a mental state of surrender. One particularly effective method involved dropping leaflets warning of impending bombings and providing methods of safe surrender as well as a guarantee of safety afterward.

With time, the messages included admissions by surrendered soldiers that they were treated well by enemies, which led to mass surrenders as Iraqi troops chose to capitulate rather than face coalition forces. Over 29 million leaflets were dropped on Iraqi troops, with thousands surrendering after receiving them.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, U.S. PSYOP (Psychological Operations) units played a critical role in breaking the morale of Saddam Hussein’s regime by targeting public perception and weakening the image of Hussein and Iraqi forces in the minds of the public. Their tactics included disseminating propaganda, spreading disinformation, and conducting psychological operations to destabilise the regime.

One of the most iconic moments of the invasion was the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue in Firdos Square on April 9, 2003. Using its command over the global narrative, the USA broadcasted it globally as a symbol of the regime’s downfall. On the face of it, the event appeared spontaneous, but later reports suggested that U.S. forces played a significant role in orchestrating this event, and the rest of the job was done by its media operations.

U.S. troops provided logistical support, including a Marine vehicle to help pull down the statue, and encouraged Iraqi civilians to participate, making the event appear more widespread than it may have been. Additionally, PSYOP units spread rumours that Saddam had fled the country, further destabilising Iraqi forces by creating panic and reinforcing the perception of the regime’s collapse. These psychological tactics were instrumental in shaping the narrative of the invasion and accelerating the fall of Saddam’s government.

Drug Trade and Organised Crime

While claiming to be always at war with drugs, the U.S. government has used the drug trade and organised crime as mere tools—with no morality involved—to achieve its foreign policy objectives. The Deep State has funded drug cartels and paramilitary groups to destabilise foreign governments and promote corporate interests. More particularly, the CIA is said to have been involved in numerous drug trafficking operations, often in collaboration with USAID and other agencies.

USAID has historically served as a tool for covert U.S. operations, enabling the use of drug trafficking and organised crime to destabilise governments and promote U.S. interests while helping its nation maintain a humanitarian facade. In multiple regions, USAID-backed programmes have facilitated the movement of narcotics and supported criminal networks, providing critical funding for paramilitary groups and political manipulation.

In Southeast Asia, during the period when the U.S. Army was involved in the Vietnam War, USAID is believed to have played a key role in financing and supporting drug trafficking through the CIA-backed Hmong militia led by Vang Pao. The powerful militia controlled opium production in the Golden Triangle. Funds given for humanitarian efforts by USAID were used to purchase aircraft from CIA-front companies such as Air America, which were then used to transport heroin across the region.

This model of using aid organisations as a cover to support drug networks was later replicated in other conflict zones like Afghanistan and Latin America. In Afghanistan, USAID programmes were closely tied to the opium trade, which became the backbone of the regional economy and a major source of funding for U.S.-aligned warlords and militias.

During the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan, opium production surged, so much so that at its peak, the country was supplying 95 per cent of the world’s heroin. USAID played a controversial role in this context, as its irrigation and agricultural programmes facilitated (indirectly, of course) the cultivation of poppy fields, ensuring the continued propagation of the heroin trade. While publicly advocating counter-narcotics measures, U.S. policies often supported drug-linked warlords and militias. The U.S. Institute for Peace, a USAID-affiliated entity, reportedly advised against shutting down opium production, citing potential economic and humanitarian consequences.

This pattern echoed earlier U.S. operations in the region, notably the CIA-backed Mujahideen insurgency during the 1980s, which relied heavily on drug money laundered through Pakistani banks like BCCI. The Golden Crescent’s narcotics trade, nurtured by Western intelligence interests, helped sustain militant groups aligned with U.S. objectives. The use of USAID as a cover for illicit economic networks has been a recurring strategy in U.S. foreign policy, where narco-economics were weaponised as instruments of statecraft.

During the Iran-Contra affair in the 1980s, USAID is said to have been involved in facilitating cocaine trafficking to support the Nicaraguan Contras. After the 1988 ceasefire, Congress authorised non-lethal aid to the Contras, for which USAID was deployed due to its expertise in administering food and medical supplies. However, declassified documents and investigations, including those by journalist Gary Webb (in his Dark Alliance series) and the U.S. government, reveal that some transport companies – including SETCO Aviation and DIACSA, involved in the delivery of these aids – were closely linked to the trafficking of drugs. The CIA, working with the blessings and goodwill of USAID-supported fronts, allowed the transportation of cocaine. The profits from these drug sales were channelled back to arm and finance the Contra rebels, who were engaged in a U.S.-backed campaign to overthrow the socialist government in Nicaragua.

USAID’s humanitarian projects in the region served as a front to obscure these illicit operations and provided infrastructure to shield the drug pipeline from scrutiny. Although the CIA was aware of these activities, investigations, including those by 5th Deputy Attorney General of the United States Counsel Lawrence Walsh, found no concrete proof of U.S. agencies’ active involvement in drug trafficking, which is anyway an expected outcome of any investigation on the deep state.

In Latin America, USAID has continued to play a critical role in funding initiatives that intersect with organised crime. Programmes ostensibly aimed at judicial reform have been used to empower U.S.-aligned legal entities to suppress political rivals while shielding criminal organisations that cooperate with U.S. interests. USAID-sponsored NGOs in countries like El Salvador have been accused of obstructing government crackdowns on drug cartels under the guise of defending human rights, thereby protecting organised crime elements beneficial to U.S. strategic goals.