USAID funding scandal: In the last part of our series on Deep State, we shed light on key faces associated with USAID. Through notorious agencies like the OCCRP, NED, USAID and others, the Deep State ‘assets’ have been exploiting people’s sympathies and their kinder side to go after Nationalist politicians. This article pieces exposes the economic coercion as part of their modus operandi through which these organisations go after politicians, countries, and nationalistic voices in their target nation.

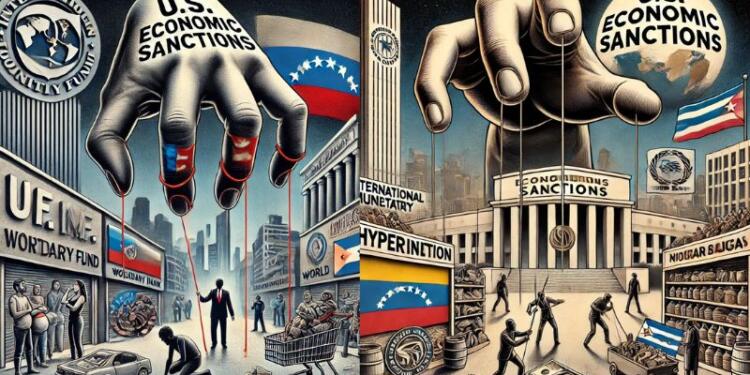

The US government has used economic pressure as a tool to influence foreign governments. This broad umbrella term includes conditioning (by American as well as U.S.-funded institutions) financial aid on economic reforms, sending inimical countries out of internationally organised economic marketplaces, and using international financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank to pressure countries into adopting policies that align with U.S. interests.

The United States has historically used economic pressure to influence foreign governments, often leading to significant financial turmoil. The impact of these measures can be seen in Venezuela, Iran, Cuba, Nicaragua, Chile, Malawi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where U.S. sanctions, trade restrictions, and aid manipulations have caused hyperinflation, currency collapses, food and medicine shortages, and major declines in GDP, among others. Oil, public services, healthcare, and essential commodities have been the most affected sectors.

In Venezuela, U.S. sanctions had a devastating impact on the country’s oil-dependent economy. Since the imposition of financial restrictions, Venezuela’s GDP has suffered a loss of nearly $700 billion, with the loss of the oil industry—whose contribution to Venezuelan GDP was 95 per cent—alone being approximately $232 billion. Add to that the freezing of $22 billion of Venezuelan assets in international banks, creating a sense of uncertainty for investors looking to pour money into the economy.

The uncertainty caused hyperinflation in the country—so much so that it has a special Wikipedia page dedicated to the phenomenon. Inflation reached an all-time high of 1,30,060 per cent in 2018, followed by 9,586 per cent in 2019 and 2,963 per cent in 2020. The government’s capability for health spending resulted in only 1.8 per cent of its GDP being used for healthcare spending. The corresponding figure was 8.1 per cent in 2008. Apparently, more than 62.5 per cent of healthcare spending in 2017 was done through out-of-pocket expenditure.

Venezuela’s healthcare system collapsed under severe shortages of medical supplies, inadequate infrastructure, and a mass exodus of medical professionals. Towards the late 2010s, hospitals reported up to 95 per cent shortages in medicine, while pharmacies faced 85 per cent shortages. It forced patients to procure their own supplies for surgeries, including basic items like needles and antibiotics.

In a 2016 poll, 76 per cent of public hospitals lacked basic medicines, and Human Rights Watch confirmed that most of the hospitals had none of the WHO’s essential medicines, including antibiotics and cancer treatments. 1,557 patients died due to short supplies between November 2018 and February 2019. The long wait for medicines put 300,000 people at risk in the year 2019.

Infrastructure failures have exacerbated the crisis, with 80 per cent of Barrio Adentro clinics closed by 2017, leaving remaining clinics overwhelmed and understaffed, sometimes serving 6,000 people per doctor. 70 per cent of hospitals suffer due to infrequent water supply as medical staff had to schedule surgeries around water availability.

Hospital bed availability went critically down, with only 16,300 of the 45,000 public hospital beds in use. Even if privately available hospital beds are taken into account, the country of 3 crore people did not have more than 25,000 beds at the peak of American sanctions.

Worse, ICU care got even bleaker as there were only 84 ICU beds available nationwide, and there are no reports of the Covid-induced introduction of 1,200 ICU beds coming to reality. Frequent blackouts have made healthcare even more inaccessible. 79 patients died in hospitals between 2018 and 2019 due to power outages. In one single month of March 2019, hospitals suffered 507 hours of electricity shortages.

High stress, fewer facilities, and intense public scrutiny led to 22,000 doctors leaving Venezuela between 2012 and 2017. A large section of those who remained ran their practices illegally or through fake degrees for wages as low as $4–$10 per month. The unavailability of cheap fuel due to a decline in production made it difficult for willing doctors to reach hospitals.

Like Venezuela, Iran’s economy has also suffered greatly under U.S. sanctions, particularly after the Trump administration withdrew from the nuclear deal in 2018 and reimposed the financial version of Democrats’ cancel culture. The Rial, Iran’s national currency, has suffered constant depreciation, hitting a record low of 892,500 rials per U.S. dollar (in unofficial markets) in February 2025.

Inflation surged as consumer prices for domestic goods rose by 30.23 per cent in 2016, 34.70 per cent in 2019, 40.19 per cent in 2021, and 45.75 per cent in 2022. But Trump only worsened what earlier American Presidents had done to Iran. Even during the Obama era, Iran’s GDP per capita fell by 35 per cent between 2012 and 2014, with the minimum wage plummeting from $275.40 in 2010 to $155 in 2012. The sanctions continue to limit Iran’s access to international markets, keeping inflation high and reducing purchasing power for ordinary citizens.

According to a United Nations General Assembly resolution in October 2024, the U.S. economic embargo has inflicted damages worth $1.499 trillion in losses when measured against the U.S. dollar’s value in gold on Cuba’s economy. Over the last 18 years alone, the island nation has suffered $252 trillion in economic losses due to restrictions on trade, finance, and access to essential resources.

It has significantly hampered Cuba’s ability to import fuel, spare parts, and other critical goods, causing widespread power outages, rationing of food, and disruptions in medical services. From October 18 to 23, 2024, many Cuban families endured long periods without electricity or running water, while hospitals operated under emergency conditions, and educational institutions were forced to suspend classes.

The multilateral agency estimates that the accumulated four-month cost of the blockade was $1.6 billion. This huge sum could have ensured food security for Cuban families for an entire year, while just $12 million—an amount Cuba loses in less than a day due to the embargo—could have funded insulin supplies for all its diabetic patients.

The sanctions have isolated Cuba from global financial systems, leading to downgrading of ratings and obstructing foreign investments and economic reforms that could have improved the lifestyle of an average Cuban citizen. Access to essential medicines and medical equipment is also extremely limited, leading to delays in treatments and surgeries, causing devastation to public health.

The Cuban government describes these measures as “economic warfare” and a “flagrant violation of human rights,” likening the blockade to a military siege under modern international law. Dozens of countries, including Bolivia, Iran, and members of the European Union, have condemned the sanctions as unjust and counterproductive, arguing that they hinder Cuba’s economic progress while failing to achieve their stated political objectives.

Despite these global calls for lifting the blockade—reaffirmed by an overwhelming majority of 187 out of 193 UN member states—the embargo remains in place, prolonging Cuba’s economic struggles and humanitarian challenges.

For Nicaragua, going with the man Americans did not want in charge was met with severe economic challenges due to U.S. trade restrictions and an economic embargo aimed at weakening the Sandinista government. The embargo, imposed in 1985, along with the funded civil war and internal economic missteps, led to a continuous depreciation in GDP from 1984 to 1990.

While Nicaragua could afford to cut loose on other products, the country needed money for military expenditure. It resorted to printing money to cover deficits, resulting in hyperinflation that soared past 14,000 per cent in 1988. The supply chain was massively disrupted due to widespread shortages of essential goods, mass unemployment reached 25 per cent (a gross underestimation), amidst a 35 per cent drop in real per capita income between 1980 and 1990.

In Chile, during the early 1970s, the USA put economic coercion on China by pressurising it simply because it did not like President Salvador Allende’s socialist government. The Nixon administration—considered quite inert in its policies—curtailed financial aid and influenced international financial institutions to halt loans to Chile. The sanctions, coupled with internal policy challenges of socialist political doctrine, resulted in unchecked government spending, due to which the fiscal deficit reached approximately 23 per cent of GDP by 1973. Available government money with supply-side constraints amidst increasing demand was the reason inflation soared to 1,600 per cent in 1973. The resulting economic turmoil contributed to the military coup in 1973 that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power.