With almost two trillion cubic feet of ice, the Siachen Glacier is the largest alpine glacier on Earth and is located high in the Karakoram. The Indian and Pakistani troops have been engaged in conflict for years in this harsh terrain, which is both the highest and coldest combat zone in history (temperatures can drop as low as minus 52 degrees Celsius).

At the Siachen base camp of the Indian Army, the scroll of honor says, “Quartered in snow, silent to remain.” When the bugle sounds, they will get up and march once more.

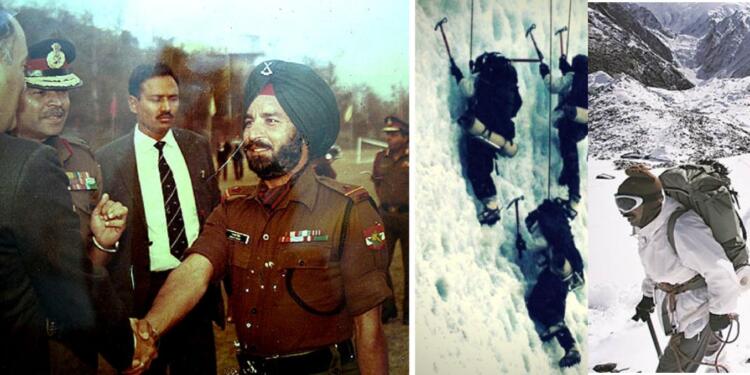

Naib Subedar Bana Singh fought the battle of his life in these freezing heights, creating an amazing tale in the process. Singh, one of just three surviving recipients of India’s highest military award, the Param Vir Chakra, was instrumental in providing the Indian army with a significant advantage during the 1987 Siachen Standoff.

In an interview Honorary Captain Bana Singh told the media that “Siachen is indispensable for India and no price is too big for it.”

In an effort to create the appearance that the area was part of Pakistan, Pakistan began granting permits to international mountaineers in the 1970s so they could climb around the Siachen glacier. It was resolved to solidify its claim by the 1980s.

If Indian intelligence had not discovered certain intriguing purchases made by the Pakistani Army in London in 1984 — large orders of specialized mountain clothing — it might have been successful (in establishing a powerful Pak-China corridor that controlled the Karakoram Pass and threatened Ladakh).

Three years later, a frustrated Pakistan planned a massive offensive to drive the Indians off their pickets near Siachen, when India was already preoccupied with the significant trouble that was developing on her northern frontier in Tibet.

Pakistan managed to build a station near the Bilafond Pass on the Saltoro ridge through a covert invasion; it was so significant that it was named after its Quaid-e-Azam, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. The glacier and India’s defense positions were now clearly visible to the Pakistani troops from that location. The position started tracking helicopter movements, identifying Indian patrols, and firing artillery against India’s supply lines.

Only three soldiers survived after the Pakistanis shot down a reconnaissance mission led by young Lieutenant Rajiv Pande in May 1987, killing nine men. It would be only a few weeks before their bodies were recovered.

The task of leading a company of chosen men up a perilous 1500-foot ice wall from Point Sonam—an Indian Army garrison at 19,600 feet surrounded by crevasses—was assigned to Major Varinder Singh of 8 JAK LI unit a month later.

The group began their treacherous ascent on June 23 at 8 a.m., but due to extremely poor weather, they were only able to travel 150 meters of the 90-degree grade slope before 4 a.m. the following day. The soldiers refused to retreat when the party was asked to return. They were aware that none of the guys would return if they failed to reach that station.

The crew remained on course to execute the last assault, their spirits bolstered by a few sips of tea, some chocolate pieces, and their unwavering bravery.

Initially dispatched for the lead attack, Subedar Harnam Singh and his small group suffered serious injuries from intense fire from the Quaid Post. Subedar Sansar Chand was then dispatched with a second small group, but they lost communication with him shortly after.

Major Varinder Singh, who had been shot in the chest earlier in the operation, then personally selected Naib Subedar Bana Singh and two other men for the lead attack. However, Singh remained out in the open for a full day until reinforcements arrived in the form of five soldiers after the health of the two soldiers declined as a result of the harsh circumstances.

According to Bana Singh, “the group was exhausted but Pande had to be avenged, and the relentless firing from Quaid reminded us of what we had to do,” Ajai Shukla, a defense analyst, said on the defense blog Broadsword.

In the midst of a blinding blizzard, Singh’s little group started climbing the nearly vertical wall of ice and encountered the frozen corpses of nine of their fellow travelers. They persisted in their steady and stealthy ascent to the enemy bunkers at the top, never giving up and even more determined.

Singh and his soldiers then launched a spectacular attack to clear the station of every single infiltrator, setting an example in high altitude combat that would earn him the nation’s highest ranking gallantry honor.

Singh and his troops ran across the fire zone, firing and lobbing grenades at the enemy with complete disregard for their own safety. They also bayoneted the enemy soldiers outside the bunker using hand-to-hand combat.

In order to eliminate the six Pakistani soldiers who were holed up inside and rid the post of all infiltrators, Singh himself threw explosives into the bunker before shutting the entrance. Later, it was discovered that the enemy soldiers were members of Pakistan’s elite Special Services Group, specifically the Shaheen Company.

The winning Indian troops then redirected their weapons, which had been pointed southward toward India, against Pakistan in the north. After that, they prepared some rice on the bunker’s Pakistani stove, which was their first meal in three days.

Next, the victorious Indian soldiers turned the guns (that were aimed in the southern direction towards India) towards Pakistan in the north. They then used the Pakistani stove in the bunker to make some rice — the first meal they had in three days.

“We had no strength to celebrate. At 21,000 feet, nobody does the bhangra or yells war cries. Ultimately, sheer doggedness iwins. If we had once hesitated, Quaid would still be with Pakistan” Singh subsequently told Broadsword.

By 5 p.m. on the evening of June 26, 1987, the Indian flag was flying high at the Quaid Post, thanks to Singh and his courageous men. It was eventually renamed Bana Top in Singh’s honor, which is how it is still called today, as a fitting homage to the valiant coup that India had used to regain the post.

Bana Singh received the Param Vir Chakra for “conspicuous bravery and leadership under most adverse conditions.” Along with the late Major Ramaswamy Parmeswaram, he is the only soldier to receive this honor during peacetime; normally, it is only bestowed for exceptional military valor in times of conflict. He subsequently received the honorary title of Captain.

After 32 years of outstanding service to the country, Singh quietly resigned a year after the Kargil War ended (during which he was the only PVC awardee still in the Army). He then went back to his hometown of Kadyal in Jammu, where he was born. He currently resides in a modest house surrounded by a farm, and his son Rajinder Singh has followed in his distinguished footsteps by joining the Indian Army