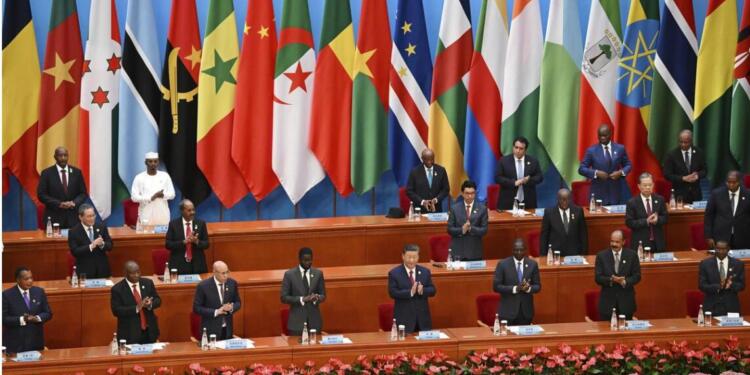

As African leaders gather for the 8th Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in Beijing, the reality of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is becoming increasingly apparent: the continent is navigating a maze of unfulfilled promises and mounting debt. Once hailed as a game-changer for infrastructure development, the BRI is instead delivering a landscape of unfinished projects and ballooning financial burdens.

The initial allure of China’s investment was undeniable. Back in 2008, former Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade praised China’s efficiency and willingness to fund African projects without the stringent conditions imposed by Western donors. China seemed poised to transform Africa with swift construction of highways, ports, and urban rail systems. But the reality has turned out to be starkly different.

In Kenya, the BRI-funded Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) was expected to revolutionize transportation and boost economic growth. However, after the initial excitement, the railway has faced operational issues, including poor management and low passenger numbers, leading to financial losses. The infrastructure, which was meant to connect major cities and stimulate trade, remains a costly burden, with debt repayments straining the country’s finances.

Similarly, in Sri Lanka, the Hambantota Port, built with Chinese loans, stands as a symbol of overreach. Originally promised as a thriving commercial hub, it has struggled to attract significant traffic. Sri Lanka’s inability to generate the anticipated revenue from the port has led to mounting debt, forcing the country to lease the port to a Chinese company in a bid to manage its financial obligations.

In Mozambique, the construction of a coal terminal funded by Chinese loans was intended to support the country’s mining sector. Yet, the project has faced delays and cost overruns, with the terminal failing to achieve its projected operational targets. The resulting debt has placed Mozambique in a precarious financial situation, with limited economic returns from the investment.

In Zambia, the expansion of road networks and the construction of new infrastructure under the BRI have not translated into the promised economic boom. Instead, the country is grappling with escalating debt and a slower-than-expected economic impact. The roadways, while built, have not sufficiently stimulated economic growth or improved daily life as envisioned.

The pattern is clear across these projects: grand promises of infrastructure and economic upliftment often give way to a sobering reality of underperforming assets and growing debt. The BRI’s legacy in Africa is increasingly marked by incomplete ventures and financial strain, as the continent finds itself ensnared in a cycle of debt with little to show for the investment.

As African leaders head to Beijing once more, their hopes are tempered by the past. Will this year’s Forum on China-Africa Cooperation yield tangible results or simply continue the cycle of lofty pledges and unmet expectations? If history is any guide, African nations may face another round of grand announcements and mounting debt, with the much-anticipated infrastructure revolution remaining just out of reach.