Reputation is the cornerstone of any individual’s place in society. Consequently, the right to reputation finds its way into the legal system. And that is where the problem begins. The tightrope between eliminating definitional ambiguity and maintaining the original notion has the possibility of creating more harm than the dangers the legal system wishes to eliminate.

Woman officer relieved of charges

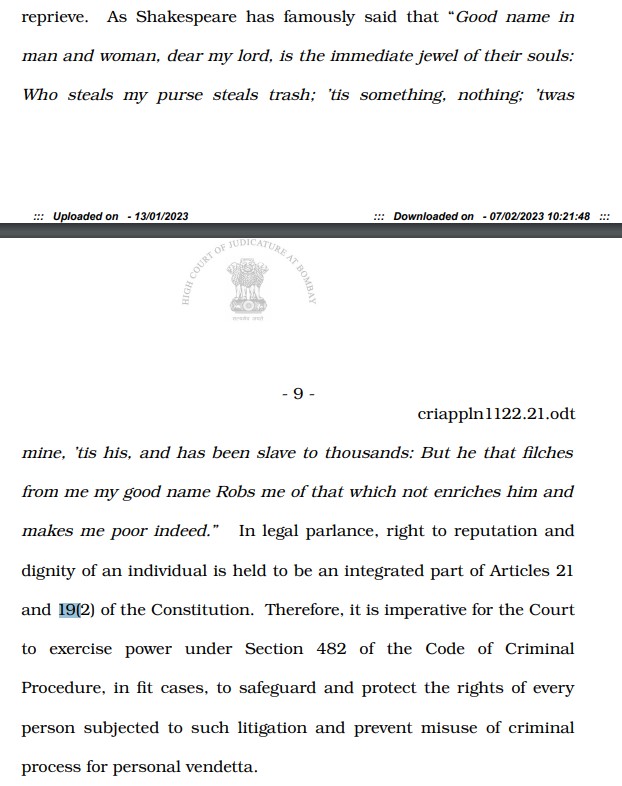

Recently, a division Bench of Bombay High Court quashed an FIR against a woman judicial officer. Charges on her included Section 498A, Sections 323, 504, 406 and 506 of the IPC, and Section 3 of the Dowry Prohibition Act. Using its power under Section 482 of CrPC and Bhajal Lal case, the High Court quashed the FIR.

In its reasoning, the High Court observed that it could lead to loss of reputation. The Court went on to quote Shakespeare and the Indian Constitution. It added that the Right to reputation is part of Article 21 and 19(2) of the Constitution.

The right to reputation is one of the most disputed subsets of Right to Life defined under Article 21.

Definitional ambiguity

The definition of reputation roughly stands as a person’s good name, honour and what the community thinks of him or her. Cornell law school sums it up as “Reputation is the general esteem held of a person’s character and comportment.” To prove reputational damage, a person has to first prove that he or she has a respectable place in society. The second part of the trial involves proving that it has been harmed. Third part involves that the person harming it did it with intention and not by mistake.

With each and every step, the issue gets further complicated. No one can define what general esteem is, except for politicians and big corporate heads. They can statistically prove it through the number of votes they get in elections and board elections respectively.

What about the rest 99.99 per cent? At best, their reputation is only at a crossroads. A journalist may show his or her YouTube subscriber chart, but then again what if the dislike button has been clicked more than the like one. What if the comment section is full of criticism?

Talking about the offline world, a well-reputed person or organisation may turn out to be negative when people are allowed to raise their voice against it. Alternatively, the media can easily tarnish their reputation, just by showing only negative side of them. It took only months to take down the reputation and legitimacy of Khap panchayats.

Also Read: Bilkis Bano Case Takes Centre Stage as CJI Forms Special Bench

Conflict with freedom of expression

And that gets us to the other side of the story. If we stop the media from covering something only because covering it risks reputational harm, then their freedom of speech is at risk. In the Noise Pollution Case, the Apex Court reiterated it. A Book allegedly defamatory of Baba Ramdev was also taken out of book shelves because of this very reason.

At the end of the day, reputation is a social issue. People live and die for the sake of it. They have their own sets of parameters. Using millions of such sets to come up with a fixed definition of reputation is next to impossible. But, then again, that is the beauty of law. This definition keeps changing and cases keep mounting.

Support TFI:

Support us to strengthen the ‘Right’ ideology of cultural nationalism by purchasing the best quality garments from TFI-STORE.COM