Ram Manohar Lohia case: When we talk about Ram Manohar Lohia, discussions always move towards the socialist leader attacking Nehru. Such is the nature of our polity that politics rules the rooster. But there is another side to his battle. Knowingly or unknowingly, he played a key role in breaking the back of the First Constitutional Amendment proposed by Nehru.

Innovative methods to curtail free speech

The British had enacted the U. P. Special Powers Act of 1932. Section 3 of the act penalised any person who would ask a certain class of people not to pay tax. It is not tough to decipher the Britishers’ intent behind it. They wanted to stop Indians from speaking their mind. Now, in 1947 the British left the country, which ideally would mean that the Section should have gone with them. Another reason for putting the section in the dump yard would have been that it violated the fundamental rights of free speech and hence was violative of Article 13 of the Constitution.

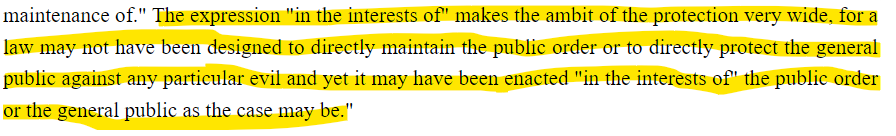

But, it did not and continued to be applicable. Instead, it was given bigger teeth by Nehru’s 1st constitutional amendment. Nehru amended Article 19(2) and effectively said that free speech could be curtailed if it goes against the “interest of public order.” While Public order is in both state as well as concurrent lists, until the amendment was introduced, maintaining public order was understood to be the foremost role of government. The government was given specific powers under the Indian Penal Code, The Code of Criminal Procedure and The Police Act to “maintain” public order.

But by using the word “interest of public order”. Jawaharlal Nehru gave it a wider meaning. Now, it became constitutionally valid for the government to curtail any speech by using this logic. Even a speech which is remotely associated with disobeying government orders was now being construed as against the “interest of public order”. The phrase emboldened Section 3 of the U. P. Special Powers Act of 1932.

The Ram Manohar Lohia Case

Ram Manohar Lohia also committed a similar offence. He gave two speeches where Lohia asked farmers not to pay heightened irrigation rates to the government. Ram Manohar Lohia was arrested and charged under Section 3 of the aforementioned act. Ultimately the matter went to Apex Court. Here the Constitutional validity of the Section was to be tested.

The Court tested the restriction on Lohia’s speech on mainly two grounds; interest of public order and reasonableness of the order. Regarding “interest of public order”, Apex Court relied on judgements in the Debi Saron case, Virendra Case and Ramji Lal Modi Case. Citing these Judgements, Apex Court acknowledged that the First Constitutional Amendment gave greater power to the government at the top.

Also read: 1st Constitutional Amendment: How Nehru sowed the seeds of communism

The distinctive line on the power of government

The Court also analysed Nehru’s intention to amend Article 19(2). It cited the governments’ dissatisfaction on the Courts’ decisions in Brij Bhushan and Romesh Thappar Cases and said that the expression “public order” was inserted to nullify the effects of those judgements.

![]()

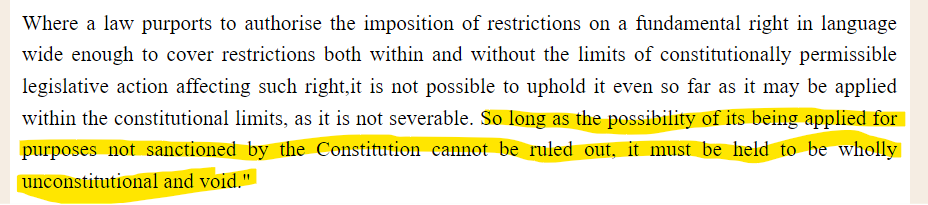

Then the Court proceeded to define reasonableness. The Apex Court took due care of not crossing the Laxman Rekha of legislative line and deciphered the definition of reasonableness from the intent of the legislature. Quote, “The restriction made “in the interests of public order” must also have a reasonable relation to the object to be achieved, i.e., the public order.” The restriction has to be in close proximity to the public order. The Court reasoned that if that formula is not applied, then it would lead to the end of the scope for any kind of agitation in the democratic set-up.

Also read: Free Speech Case: We have some questions for the Indian judiciary

Then the Advocate General rushed in to defend the Constitutionality of the aforementioned Section by stating that the Section can be operated in such a way that it stands the test of Article 19(2). But the Court shunned the argument by stating that even it won’t kill the chances of its use by bad faith governments. Simply because misuse like that of in the Ram Manohar Lohia Case will still be Constitutionally valid.

The Apex Court ultimately declared the Section in question as Ultra Vires. But the case is remembered more for a line between government overreach and citizens’ right to protest. Ram Manohar Lohia may be a socialist, but this case prevented almost absolute Communist type control of freedom of speech. Ironically, a socialist was becoming a victim.

Support TFI:

Support us to strengthen the ‘Right’ ideology of cultural nationalism by purchasing the best quality garments from TFI-STORE.COM

Also Watch:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SxxNUkh7OWU