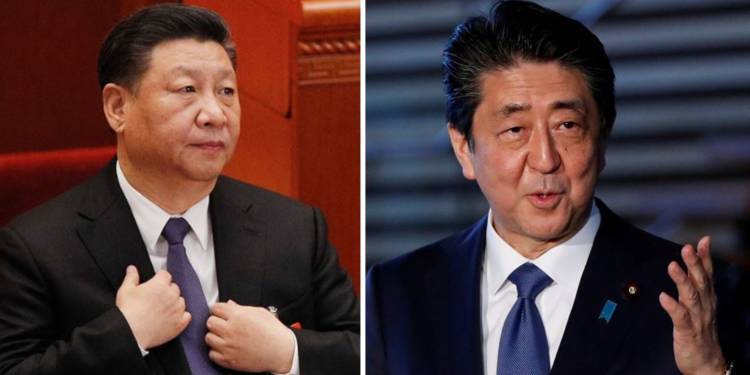

Xi Jinping is fighting all kinds of battles- the Coronavirus backlash, Trump’s trade war, the Huawei snooping allegations and border tensions with India and Japan. Beijing wants to weaponise everything that it can from trade relations to foreign investments. But no matter how much it is tempted to, China cannot weaponise its most important advantage- its dominance in rare earth metals. The reason for this is Japan, which has over a period of time shattered the myth of the Chinese monopoly on rare earths.

China holds an effective edge on rare earth metal production. It accounts for 70 per cent of the global production. China’s State media and officials have regularly wielded threats to cut the United States off the rare earths supply. CCP mouthpiece Global Times has gone to the extent of saying that the minerals that the US relies upon are “an ace in Beijing’s hand”.

The Chinese chorus to block the supply of rare earth metals to the US has intensified after the Trump administration decided to ban the supply of microchips and other components to the Chinese telecom giant, Huawei. This virtually threatened the survival of the telecom major.

Rare earth elements, a suit of 17 elements, are strategic assets. Rare earth elements like neodymium, which is used in magnets, and Lanthanum, Scandium, Europium all have unparalleled significance in the tech, IT and defence sectors. They are used in the manufacture of semiconductors, batteries and defence systems. Production of fighter jets, hypersonic missiles, electric cars, satellites, smartphones, lasers and radiation-hardened electronics- everything is dependent on this group of 17 elements.

Deprived of rare earths, a civilisation would be set back by a few decades. No country, more so countries like the US, Japan or Australia can afford to be drained out of rare earths supplies. But rare earth metals are no oil. They cannot be weaponised in geopolitics and Japan proved this in 2010.

Beijing had tried to use its effective monopoly in rare earths against Japan in the year 2010. The paper dragon was driven by a territorial dispute to take the extreme step. But it turned out to be a major miss and China regrets weaponising the rare earths sector till date.

Compelled by China’s aggressive geoeconomics in 2010, Tokyo was compelled to look beyond China to procure rare earth metals supplies. Supply chains were built outside China, as the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry introduced an initiative aimed expressly at “escaping China”.

Tokyo moved ahead with diplomatic efforts in countries like India, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Vietnam that had rare earths potential but lacked the investments and capacity to extract them. Japan registered a huge success, as by 2017, Japan was importing around 30% of its rare earth metals from countries in Asia other than China.

The Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) also moved ahead with projects in the US, South Africa, Brazil, Chile, Kazakhstan, and Malaysia. It is because of Japan’s Initiative that China’s share in the world’s supply dropped from more than 95 per cent in 2010 to less than 70 per cent in 2018 and it continues to fall.

Today, China is feeling a very strong urge of blocking the supply of rare earth metals to the US. Xi Jinping himself manifested this strong temptation when he visited a rare earths processing firm in the Jiangxi province, and that too after Trump’s move to restrict the supply of semi-conductors to Huawei.

But China has to hold back because every time it thinks of punishing Trump or Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison, it is reminded of what Japan did to Beijing in 2010.

Through the 2010 episode, we have come to realise that rare earth metals are not ‘rare’ because of scarcity. According to the US Geological Survey, rare earth metals are actually “moderately abundant” in nature. They are ‘rare’ because they occur in chemical compounds. It is costly and environmentally complicated to extract them, but in no does this mean that China has a complete monopoly in rare earths.

China is not the only country that has rare earth metals deposits. The US itself has rich deposits of this group of 17 elements. China is estimated to have around 37 per cent of the world’s rare earths. Even Washington’s friends- India, Brazil, Australia, Canada and South Africa, have sufficient rare earth deposits.

China has been able to build a so-called monopoly only because of State intervention in the mining and extraction process. Chinese spurt in rare earths production is driven by State-funding in infrastructure and technology since the 1990s.

But what will happen if China tries to weaponise the make-believe rare earths monopoly against the US? Will the US suffer substantially? A practical analysis makes us believe otherwise.

Last year, the US imported around 10,000 tonnes of rare earths from China. This is a modest 0.001 per cent of the US Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In the event of China cutting off supplies to the US, Trump can easily fall back upon private and public stockpiles in the short-term. In the mid-term, the US would be able to augment its own production. The US will meet its own needs like Japan did in 2010 and China would get further marginalised in the global supply chains.

In fact, Japan is again cooperating with the US and Australia to limit China’s rare earth dominance. The US itself is encouraged by Japanese cooperation and eager to cut dependence on China. Earlier this year, the Pentagon proposed a legislation to end reliance on China for rare earths.

The proposed legislation seeks to raise the spending caps under the Defense Production Act, so that 1.75 billion Dollars can be spent on rare earth metals in defence equipment and 350 million Dollars for microelectronics.

The bottom line is: Japan has proved that China has no real monopoly on rare earth metals. All this while, the world has allowed China to dominate the strategic industry. But Japan has shown that this dominance can be ended at will, if intent is shown to build new supply chains.