There are those that need mending and there are those that mend. There are overwhelmingly those that are well and then there are those that aren’t. An illness is an anomaly that we treat. It is something we do not want to live with and we do not wish a loved one be afflicted by. A clinic, a dispensary or a hospital are spaces that we hope we don’t have to linger long. If fate has it that we need to visit one often or we’re admitted ourselves we tend to develop a kingship of shared empathy for those we meet in corridors and labs. As caregivers of loved ones, each visit by the doctor is a moment we gear ourselves up to listen to an educated informed verdict, a verdict on progress, and sometimes not. We hinge our hopes on every word uttered, we seek answers for every possible question and we thrust our hopes on them with such expectation that we don’t realise how difficult it is for them to speak the truth, sometimes the inevitable with the burden of the sorrow and tear their opinion might bring to us. More than when we are sick ourselves but we care instead for loved ones do we realise the pain, the heartbreak, the stress, the desperation of dealing day in day out with something that is broken. For a doctor, that is a default situation. When we walk out of the hospital gates with a mended body or a body left behind, in either case we know that we are ultimately in a better space outside those gates than within.

Yes, it is science, yes it is a job, and yes there were no unexpected surprises of a fundamental nature when one chooses to be a healer. When you choose to study medicine you have consciously opted to have a lifelong relationship with the broken, the dysfunctional, the dying. From a high level the profession can be highly commercial and extremely corrupt even, but in my life, in the inexplicable bond of hope and faith and illness and stress, in that tiny unique circle of the doctor and I or the doctor a dear one and I, I have seen overwhelmingly that doctors and the entire spectrum of health caregivers give a little bit of themselves to your cause. And I am sure I am not alone in experiencing this. In that kinship in the corridors I spoke of earlier about when attendant talks to attendant and patient talks to nurses, there echoes often that same sentiment. It is not fair to think that despite mechanisms they surely have to adapt to survive disease and death day after day, a doctor is able to consider a person to just be an agglomeration of cells and organs and chemical reactions. Among professions it is widely regarded to be among the most stressful. There are pressures, hopes, expectations of miracles from families and loved ones of patients, moreover patients themselves that can be difficult, delicate, precarious, serious, unfortunate and outright tragic. There is too the immense stress of decisions that are literally about life and death. These are sick human beings they deal with, making decisions that could alter the course of lives irreversibly. It isn’t like an inanimate car part being changed is a garage. It is a body being cut open and fixed for a new lease of life or relief from pain and distress.

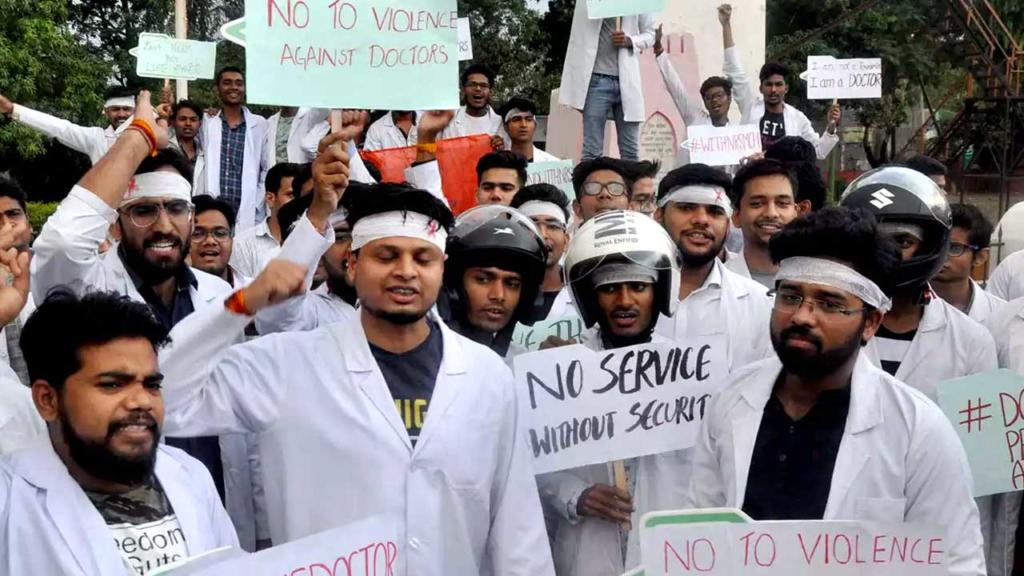

When the medical profession goes on strike, it is very easy to understand why this feels instinctively unethical. Their strike does not mean shutters are down or a loss of sales and money, their strike means the sick are not looked after, the dying are left to die, the pain not alleviated and the extension of suffering. Most often strikes are not full shutdowns either, because essential services have a certain relentless nature about them. But because of the nature of the profession a strike can hold a vital service at ransom and bring the establishment and administration to its knees very quickly. But there are strikes and there are strikes. When the consequence of the death of an 85 year old patient results in the rampage of a hospital and renders a doctor comatose with a smashed skull, only the utterly utterly self-centred would fault doctors for going on strike demanding not the moon and the sky but an apology and security.

In a civilised world, such mob violence in a hospital would never have happened in the first place. Death is not an anomaly. Its inevitability is known to all. Considering that the unthinkable has happened and doctors doing their job have to have their skulls dented for it, the immediate unconditional spontaneous gesture and administrative move would have been to call on the injured by the powers that be and ensure immediate security. But in the dangerously chaotic jungle rule that is Bengal, two days into the tragedy and the takeaways were the demented notions of Bengal for Bengalis and bikers are outsider hooligans.

As witnesses to this descent into inhumanity the word “impotent” for the hapless citizen has taken a whole new spin and plunge in connotation. We hear and watch and outrage in horror, first thinking surely in this day and age such unadulterated megalomaniac bunkum has got to have a check mechanism. Then we are forced to finally realise that for all its glorious tenets, civilisation, democracy, public opinion and government are but toothless organisms. A resolution of sorts did happen recently, but not after, god forbid; some young lives trained to save the lives of others paid for it themselves for something they didn’t do wrong. Never did I wish so strongly for a Waterloo moment for the government of Bengal. In the steadfast defiance and solidarity of the medical fraternity, I hoped to see a definite turn around. In my solidarity with the doctors, never for a moment did I cease to think of the patients and families of those in pain. It was indeed an ugly reflection of the extent mankind can plunge when we needed to stand by doctors who had gone on strike to seek protection for their lives so that they could save the lives of others.