We are going to talk about a Financially gigantic, infrastructurally multifaceted and incredibly ambitious program that would take about 43 Years to complete provided there are no benefits. It will cost the nation about Rs. 1,10,00,00,00,00,000 (11 Lakh Crore Rupees).

We are talking about the National River Linking Project that promises to be a watershed moment of Modern India. BUT Will it really deliver?

The idea of linking rivers is not new and dates back to British Colonial rule – but back then, it was to reduce transportation cost of British supplies. Then sometime in the 1970s, Dr. K.L. Rao proposed the idea of ‘National Water Grid’ and Dastur proposed a ‘Garland Canal scheme’ to feed Himalayan waters to the peninsular parts of the country by means of pipelines. It was not until the National Water Development Agency (NWDA) was set up in 1982, that we took the concept seriously. The agency carried out detailed studies of the interlinking project in the context of the National Perspective framed by Ministry of Water Resources. Although, none of the proposals were found unworthy of implementation but the idea lurked around. Supreme Court has many times criticized the government for delaying it – which is no surprise since all creditworthy ideas were delayed by Congress regime.

The modern shape of the National River Linking Project, first proposed by BJP-led government in 2002 is a gigantic, multifaceted, and is incredibly ambitious government project which has the potential to transform – economy, agricultural landscape, irrigation, water navigation, India’s energy sector and much more. Its successful implementation will be a watershed moment for Modern India.

One of the main objectives of the interlinking of rivers program (ILR) or the National River Linking Project (NRLP) is to link different surplus rivers of the country with the deficient rivers so that the excess water from the surplus region could be diverted to a deficient region. Some of the problems that the project aims to address on a large scale and the solutions are.

1] Uneven and unpredictable rainfall in India: Average rainfall is about 4,000 billion cubic meters but it is concentrated to almost 4-month period – June through September. One of the most important benefits would be to meet water shortages in drought-prone areas through inter-basin transfers. Borewells are drying up and water tables going down. By 2050, potentially usable water resource (PUWR) will go down from current 58% to 22%. National River Linkin Project will improve PUWR storage. The project would conserve the abundant monsoon water bounty, store it in reservoirs, and deliver this water – using interlinked rivers to areas and overtimes when water becomes scarce. Thereby, it will also increase irrigation intensity in the country (which is brought down by precarious monsoons),

2] A relief from perpetual floods: Mitigating the effects of persistent floods (Ganga Basin, Brahmaputra basin sees floods almost every year) by channelling down the water from swollen rivers to deficit ones.

3] Food Security and energy supplement: Agricultural productivity, food grain production, crop production is directly proportional to growth in irrigated area. Assessment of the total irrigation potential of the country is about 140 million hectares of which 76 million hectares from surface water and 64 million hectares from groundwater. This is not going to be sufficient. Moreover, changing food habits of the country calls for more provision for food security. Besides adding irrigation potential (of about 30 million hectares), it will create additional storage facilities for hydro-electric projects of about 40GW capacity.

4] A new transportation route: Creation of an alternate infrastructure for transportation of goods to reduce pressure from roads and railways is also on the offing. Riverways will also reduce oil consumption and pollution.

5] Employment Generation & Extension of Gainful Fisheries: It will support livelihoods by providing occupation through fish farming in rural areas.

6] Water abundance: Increased water availability for drinking and industrial purposes is another benefit.

These are only the main benefits that are non-empirical but evident. The project is unbelievably grand and ambitious with an estimated cost of Rs 11 lakh crores. The tri-phase project includes 14 sub projects for northern Himalayan rivers inter-link component, 16 sub-projects for southern peninsular component and 37 intrastate rivers linking projects. This includes dozens of irrigation schemes as well. It aims to link nearly 60 rivers through 30 canals network of almost 15,000 kms, 50 and 100 meters wide and six meters deep, and construct 3,000 small and large reservoirs to store 185 billion cubic meters of water. It has an estimated 40 gigawatt of hydroelectric potential and will create around 87 million acres of irrigated land. Looking at the benefits of it, the Supreme Court remarked

“This is a matter of national benefit and progress. We see no reason why any State should lag behind in contributing its bit to bringing the inter-linking river program to a success, thus saving the people living in drought-prone zones from hunger and people living in flood-prone areas from the destruction caused by floods.”[6].

Infact, It is so huge that we cannot quantify its complete impact with certainty until it is in force on the ground and many things will be a surprise. But we can take a hint from other similar successful projects around the world such as the Colorado River Aqueduct (US), the Cutzamala System (Mexico), the National Water Carrier (Israel) and many such inter-basin transfer (IBT) routes in China. All are tiny yet substantial examples of what National River Linking Project can do in the Indian context.

However, while the project brings an unprecedented excitement and future for us to the table, certain other imperative aspects cannot be overlooked. And are we really prepared for the unseen risks, such as below, related to environmental, ecological and social displacement, we need to ask.

1] Deforestation: To make way for canals, deforestation might be inevitable in some areas and local bio-reserves (such as the Panna Tiger Reserve) may suffer a considerable loss. This has to be avoided as far as possible and alternate routes that do not affect the objective must be searched.

2] Certain Ecological Imbalances are also inevitable: A lot of fresh water goes into the sea. Rivers interlinking may reduce that amount and could pose a threat to estuarine conditions and adversely effecting coastal marine eco-system. To solve this, along with interlinking, we must keep our rivers clean and away from industrial pollutants. The danger of one river getting polluted will affect the water in all the rivers countrywide. Flagship initiatives of the current government such as Clean Ganga, elimination of open-defecation, protecting rivers from industrial pollutants etc will serve as a major variable in the success equation of NRLP. In a way, it is good to see how the National River Linking Project is beautifully complemented by such initiatives. Other consequences that must be thought through would be such as hyper-trophication of water mixed bodies, depletion of oxygen and altering pH levels of water content, salinity may increase, threat posed by water-borne disease vectors, evapotranspiration from the reservoirs and canals and local ecological instability from the transfer of flora and fauna [5].

3] Local displacement: Displacement of local population living alongside the areas scouted for canals is another con aspect of this project. With an estimated displacement of about 580,000 people, state government must protect the daily lives of such people and make proper arrangements to their movement to local and nearby places. Poor people of this nation and people who are directly getting affected must be made the biggest stakeholders of this project and they must be taken into serious consideration before any conclusion can be arrived at.

4] Questions on its scientific basis, Timelines and Budget?

“A river isn’t a pipe that we can control.” Says Dr. Latha Anantha, director, CPSS and River Research Centre[8]. Can we really control how much water a natural river that has flown from centuries will have? People even justify that floods and droughts are also a natural phenomenon in a river’s life. On account of that, how much of the troubles of displacement and loss of eco-system are we willing to accept. Moreover, there cannot be a conclusion made that the project will work as expected. Have we factored in the hydrology of all the rivers, have we accounted for the complete cost of the project. We can learn from the cost of China’s South-North Water Transfer Project (SNWTP) which also aims to eliminate the twin problems of floods and droughts and that has been the subject of estimates from various quarters [9].

Have we estimated the completion time of the project right? NCIWRDP has identified that it will take 43 years for the completion of the proposed interlinking project. Commenting on the same Supreme Court, on 2002, ordered that

“It is difficult to appreciate that in this country with all the resources available to it, there will be a further delay of 43 years for completion of the project to which no State has objection and whose necessity and desirability is recognized and acknowledged by the Union of India……We do expect that the programme drawn up would try and ensure that the link projects are completed within a reasonable time of not more than ten years [10]”

How much of our data is relevant still and will be relevant over the course of this project phases? How many states are in agreement with each other to give the water when needed? All these questions pose a serious challenge to the success of the project.

5] International implications: Is it really a danger to our relations with Bangladesh, as some would suggest [7]? With the exceptions of Nepal and Bangladesh, who will be onboard with us since IRL doesn’t add up to any of their existing water problems, rather it sees benefits for 40L Bangladeshi farmers to have a permanent fishing job, we can steer clear of it smoothly. But we must keep concerned countries in the loop.

Even if we win over all the impediments, success will not come overnight. A project of this scale of engineering needs a will-full government, faster clearances, speedy negotiations with all the state and private parties concerned. The money involved in the project could lead to corruption and scams giving the nation is not completely rid of the scam-babus yet. Moreover, opposition is coming from environmentalists, wildlife enthusiasts, royal families (terming it as grave environmental disaster [4]), but if we look at the economic Impact of Drought that India suffers annually, a solution of this scale becomes immediately necessary as well [2].

So where are we now with the Project Status? A comprehensive assessment of feasibility of linking of rivers associated with the project was completed by NDWA in 2005. But so far only the Godavari and Krishna rivers linking was completed last year in September through a canal in Andhra Pradesh at a cost of ₹ 1300 crores. As a result of it, farmers have been benefitted, and the linking will also stabilized the ayacut and facilitate early seed beds in Krishna delta that faces acute water shortage during June to August [3]. The second project is the Ken-Betwa river (estimated $1.7b) is underway and will take few more months to materialize.

Are there any alternatives to ILP?

Nation-wide water conservation, artificial groundwater recharging, rain water harvesting, better agriculture practices, awareness to not waste water are some seemingly possible alternatives that have nearly 0 costs as compared to this project. They all have been tried as well and they all offer localized solutions at best. But how much of conservation can solve the problem of millions of hectare of land that go parch every Indian summer? Can it solve the problem of droughts and floods that kill hundreds of poor people, damage crops and leave agriculture in an ICU? Probably no but the NRLP project, by replenishing water tables, is believingly poised to solve it.

India is a home of variety of crops with different sowing and harvesting patters and irrigation needs. Seasonal availability of water also puts pressures on farmers to restrict with crops that don’t require much water. Digging deeper wells or Government Subsidies for agriculture are only stopgaps and cannot promise a lasting impact. But yes, we should not overlook their impacts completely. They may be best useful to plug any holes that NRLP would leave open. If basic problem of excess or shortage water are solved, then micro irrigation can be encouraged and technology can be used. Better agricultural practices such as drip and sprinkler irrigation, desalination, use of genetically modified (GM) crops (although I am not sure what are the additional pros and cons for it will be) can be perused freely.

Conclusion

Most of us are ambivalent but I believe that something this big and bold is needed. Let us, for one moment imagine a country which leaves behind its post-colonial history of draughts, floods, farmer’s suicide (due to their lands going dry), water scarcity and poverty arising out of monsoon vagaries. We have to look beyond these problems. We need solutions and we need them fast. But as said, we also must tread extremely cautiously and not get driven away by the enthusiasm of finding the perfect panacea, for there is none. There will be consequences. Ecological damage, migration of people, inconveniences, loss of forest land etc can’t be completely ruled out but we would have to minimize the ecological damage. And, if we can restore the damage, only then, for the sake of our generations, this project do seem all what we need. NRLP will have us brace for hiccups initially, no doubt, but overtime, it is not impossible to envision a nation free of water-problems.

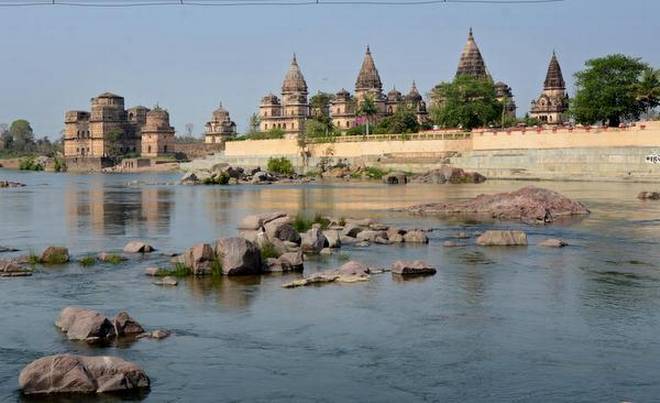

Rivers are sacred and we treat them as our mothers for they have been nourishing the soil of this land since thousands of years. It is time, we bring them together for the benefit of this nation. And when Ganga will be mixing with Narmada, Tapti with Godavari and Krishna with Kaveri, will it not be like having many ‘Prayags’ across the country instead of just one?

References

[1]http://www.nwda.gov.in/writereaddata/mainlinkfile/File277.pdf

[2] ASSOCHAM Studies: About 33 crore people need support with food, water, medicine, i.e about 25% of population. This will divert financial resources from development to aid, and the economy (including Livestock and agriculture economy)will have to brave atleast about US$ 100 billion. The loss of subsidies on power, fertilizer and other inputs due loss of crop multiply the impact.Migrate due to this will bring massive socio-economic challenges, putting pressure on urban infrastructure. Over stretched water and food supplies will trigger crime rate as well. http://www.assocham.org/newsdetail.php?id=5678

[6] Supreme Court hearing details “IN RE : NETWORKING OF RIVERS”. Can be read here. http://courtnic.nic.in/supremecourt/temp/512200232722012p.txt

[8] https://qz.com/504127/why-indias-168-billion-river-linkingproject-is-a-disaster-in-waiting/

[9] http://www.orfonline.org/research/linking-rivers-in-china-lessons-for-india/

[10]The Interlinking of Indian Rivers: Some Questions on the Scientific, Economic and Environmental Dimensions of the Proposal by JayantaBandyopadhyay and ShamaPerveen, King’s College London University of London (2003). https://www.soas.ac.uk/water/publications/papers/file38403.pdf

Other studies

Assocham studies, World Bank Data, Data from NWDA website (www.nwda.gov.in)