On this day, February 16, in 1923, English archaeologist Howard Carter entered the sealed burial chamber of the ancient Egyptian ruler King Tutankhamun in Thebes, Egypt.

The ancient Egyptians viewed their pharaohs as gods and took great care to preserve their bodies after death. They were buried in elaborate tombs filled with rich treasures, intended to accompany them into the afterlife.

By the 19th century, archaeologists from around the world had flocked to Egypt, uncovering numerous tombs though many had long been looted and stripped of their riches.

Carter, who arrived in Egypt in 1891, was convinced that at least one tomb remained undiscovered, that of the little-known Tutankhamun, or King Tut, who lived around 1400 B.C. and died as a teenager.

With financial backing from the wealthy Lord Carnarvon, Carter searched for five years without success. In early 1922, Carnarvon considered ending the expedition, but Carter persuaded him to continue for one more year.

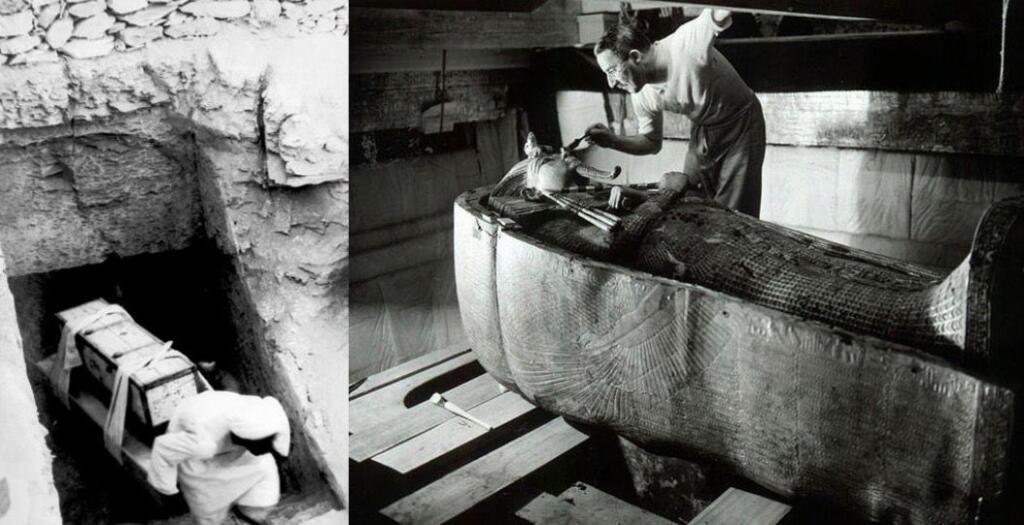

Their perseverance paid off in November 1922, when Carter’s team uncovered a hidden set of steps buried in debris near another tomb’s entrance.

It was a bright, sunny morning in the Valley of the Kings, when the team of Egyptian workers were clearing away sand and they noticed the hint of stone steps about 13 feet (4 meters) beneath the tomb of Ramesses VI.

The steps led to a sealed doorway bearing the name of Tutankhamun. When Carter and Lord Carnarvon entered the tomb’s interior chambers on November 26, they were thrilled to discover it virtually intact, its treasures untouched for more than 3,000 years.

As per reports, Carter wrote in his diary, “Here before us was sufficient evidence to show that it really was an entrance to a tomb, and by the seals, to all outward appearances that it was intact on November 5, 1922.”

The doorway was filled with rubble, likely placed by priests to block the tomb, providing further proof that it had not been looted and over the next few weeks, the team cleared the steps and the doorway until, on Nov 24, 1922, they uncovered a seal bearing the cartouche, an oval of hieroglyphs showing King Tutankhamun’s name.

The rubble contained pottery and broken boxes linked to other ancient monarchs, including Akhenaten, Tutankhamun’s father. On Nov 25, 1922, the team opened the first door to the tomb. The next day, they found a second door and carefully cut a tiny hole to peek inside.

No Egyptian officials were allowed in, but Carter brought along Lord Carnarvon, who funded the excavation, his daughter, Lady Evelyn Herbert; and Arthur Callender, the dig’s engineer all waited anxiously to see what lay beyond.

Tutankhamun’s tomb was first discovered in the Valley of the Kings by a team of mostly Egyptian excavators led by Howard Carter in November 1922.

However, it took several years for the excavators to clear and catalogue the tomb’s antechamber – the first part of what would become a decade-long excavation.

Carter wrote in his diary, “It was sometime before one could see, the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker, but as soon as one’s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another.”