The Supreme Court’s refusal to entertain a plea linked to alleged cash inducements in the Bihar electoral process has stirred sharp political debate, placing electoral ethics and legal thresholds under fresh scrutiny. The petition was associated with the Jan Suraaj Party founded by Prashant Kishor, which had sought judicial intervention over claims that money power was influencing voters. However, the apex court chose not to proceed with the matter, signaling once again that election related grievances often need to follow established statutory mechanisms rather than urgent constitutional routes.

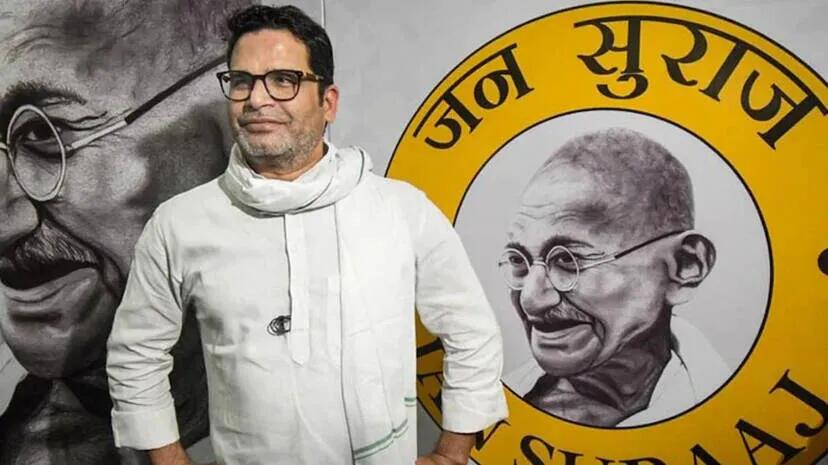

The development is significant because Bihar remains one of the most politically sensitive states in India, where electoral mobilization is intense and margins of victory can be narrow. The Jan Suraaj Party, under Prashant Kishor, has been positioning itself as a reform driven alternative focused on governance, accountability, and grassroots participation. By raising the issue of alleged cash inducements, the party attempted to spotlight concerns that have long shadowed Indian elections, particularly in states where socio economic vulnerabilities can make voters more susceptible to inducements.

Legal observers note that the Supreme Court is generally cautious about intervening directly in the conduct of elections unless there is a clear constitutional breakdown or violation of fundamental rights that cannot be addressed elsewhere. In matters involving alleged malpractice during polls, the court has often emphasized the role of the Election Commission and the availability of election petitions after results are declared. This judicial approach appears consistent with how the plea linked to Prashant Kishor was treated, with the court signaling that the appropriate remedies lie within the existing electoral law framework.

For Prashant Kishor and his political platform, the episode serves both as a challenge and an opportunity. While the immediate legal route did not yield the desired outcome, the party may use the issue to build a broader political narrative around clean elections. Anti corruption and transparency themes resonate strongly among younger and urban voters, and raising such allegations, even if not judicially examined at this stage, can shape public discourse. The Jan Suraaj Party has been trying to transform itself from a campaign consultancy rooted initiative into a full fledged political force, and issues of electoral integrity align closely with that identity.

At the same time, critics argue that allegations of cash inducements surface in nearly every election cycle across different states, yet proving them in court is notoriously difficult. The burden of evidence is high, and courts require specific, verifiable material rather than broad claims. This legal reality may explain why the plea connected to Prashant Kishor did not gain traction at the Supreme Court level. It underlines the complex intersection between political messaging and judicial standards of proof, where what works in public debate does not always translate into legal success.

The Election Commission’s role now becomes central in the narrative. As the constitutional authority tasked with ensuring free and fair polls, it has mechanisms such as expenditure monitoring teams, flying squads, and surveillance measures to curb the distribution of money or gifts to voters. If the Jan Suraaj Party continues to press the issue, it may have to rely more heavily on submitting detailed complaints and evidence to the Commission rather than seeking immediate court intervention. This institutional pathway, though slower, is the one the judiciary has repeatedly endorsed.

Politically, the move keeps Prashant Kishor in the spotlight in Bihar’s evolving landscape. Known nationally as a strategist before entering active politics, he has been attempting to build credibility as a leader who challenges entrenched practices. By associating his party with the fight against alleged cash inducements, Prashant Kishor reinforces an image of confronting systemic distortions. Whether this translates into electoral gains will depend on how effectively the message connects with voters beyond the legal headlines.

The broader question raised by the episode is about the persistent tension between electoral idealism and ground realities. India’s democratic framework is robust, yet the influence of money remains a recurring concern. Judicial restraint, as seen in the court’s response to the plea tied to Prashant Kishor, reflects an effort to maintain institutional balance, ensuring that courts do not become the first arena for every electoral dispute. Instead, the system relies on a layered approach where administrative, quasi judicial, and finally judicial remedies come into play in sequence.

In the end, the Supreme Court’s stance does not close the political conversation. It merely redirects it. For Prashant Kishor and his party, the path ahead lies in converting the controversy into sustained grassroots engagement, evidence based complaints, and a campaign that persuades voters that electoral reform is not just a slogan but a mission. In Bihar’s charged political climate, that narrative could prove as influential as any courtroom battle.