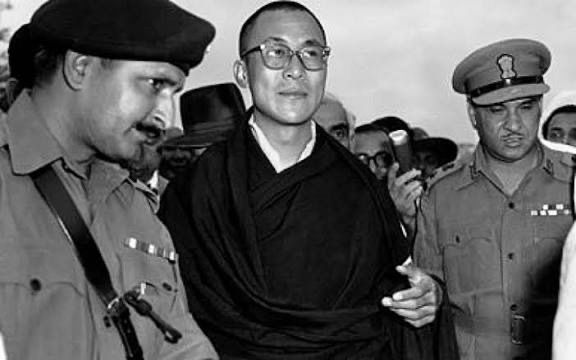

Seventy-five years ago, as Chinese forces advanced into central Tibet, the 14th Dalai Lama faced a critical juncture in Tibet’s modern history and withdrew with senior officials from Lhasa to Yadong, near the Indian border.

For several months thereafter, the Tibetan government operated beyond the reach of Chinese authority. This period marked one of the last moments in which Tibet exercised independent political decision-making under its own leadership.

That moment ended in 1951, when Beijing secured the so-called “Peaceful Liberation” agreement—signed after Tibetan forces had already been defeated at Chamdo and under the clear threat of further military action.

Today, this history is no longer confined to archives and has become the centre of a global information battle. On 14 January 2026, the European Parliament’s Inter-parliamentary Group for Tibet met to review developments and coordinate responses to Chinese claims about Tibet’s past.

Chinese officials continue to insist that Tibet has been an inseparable part of China since the 13th-century Yuan dynasty. This claim, however, is increasingly being questioned as scholars and legal experts revisit the historical record with fresh scrutiny.

The Problem with Yuan and Qing “Ancient Rule” Claims

The idea that Tibet has always been ruled by China relies on reading modern ideas of sovereignty back into very different historical relationships.

During the Yuan and later the Qing periods, Tibet’s relationship with imperial rulers is often described using the concept of cho-yon—the priest-patron relationship. In this arrangement, Tibetan religious leaders provided spiritual legitimacy, while emperors offered protection and patronage.

Many Tibetan scholars argue that this was not the same as direct administrative rule or incorporation into a Chinese state. At the same time, historians disagree on how much political authority imperial courts exercised over Tibet at different moments.

What matters is that the relationship was not equivalent to a modern province governed by a central bureaucracy. It was fluid, symbolic, and shaped by religious norms rather than territorial sovereignty.

When the Qing dynasty collapsed in 1911, the relationship itself collapsed with it. In 1913, the 13th Dalai Lama issued a proclamation declaring Tibet’s independence. He was not “seceding” from a functioning Chinese state; he was ending ties with a fallen imperial house.

For the next several decades, Tibet operated with de facto autonomy. It ran its own administration, used its own currency and stamps, maintained armed forces, and conducted foreign contacts—even though its international legal status remained disputed and recognition uneven.

Chinese historian Lau Hon-Shiang has pointed out that official Ming and Qing records often referred to Tibet as a foreign or external entity, not as an integrated part of China. This directly challenges the claim of an “unbroken” chain of sovereignty.

How Evidence About Tibet Is Being Erased

The persistence of the “ancient rule” narrative depends heavily on controlling access to information.

Within China, historical archives relating to Tibet are tightly regulated. Documents that complicate official narratives are difficult to access, reclassified or removed from circulation. In 2025, reports emerged of library “cleansing” projects that allegedly withdrew material related to Tibetan passports and Tibet’s contacts with the British Raj, even though Beijing expanded its influence through overseas academic partnerships and policy networks.

At the same time, China has invested heavily in think tanks and academic collaborations abroad by promoting the idea that the “Tibet Autonomous Region” is not just a current administrative unit but a timeless historical reality.

This strategy is becoming harder to sustain. Scholars increasingly rely on digitised archives and pre-1949 records preserved in India and the United Kingdom. These sources show a Tibet that negotiated, signed agreements, and interacted with other powers as a distinct political entity.

The Simla Convention and Tibet’s International Role

In 1914, Tibet participated in negotiations with British India and China, which led to the Simla Convention. Tibet and Britain ultimately signed the agreement, which included the boundary later known as the McMahon Line. China rejected the final text and refused to ratify it.

China’s objections were not limited to the border line alone. Beijing also disputed how Tibet’s status was described in the agreement and rejected arrangements it believed undermined its claims of authority.

Even so, the episode is important for one clear reason: Tibet negotiated and signed as a separate party. Whatever China’s objections, Tibet was treated by Britain as an entity capable of concluding international agreements. That fact alone undermines the claim that Tibet had no international personality.

Why the 1951 Agreement Lacks Legal Legitimacy

Beijing presents the Seventeen-Point Agreement of 1951 as proof that Tibet voluntarily returned to China. The circumstances tell a different story.

The agreement was concluded after the People’s Liberation Army had already defeated Tibetan forces at Chamdo. Tibetan delegates in Beijing were operating under intense pressure and were not authorised by the Dalai Lama to surrender Tibet’s sovereignty. They were repeatedly warned that refusal would result in a full military advance on Lhasa.

Under modern treaty law, coercion matters. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states that treaties obtained through the threat or use of force are invalid.

Although the Convention was adopted later, the principle it reflects—that agreements signed under military coercion have no legal standing—was already recognised as a core rule of international law.

China’s own conduct further weakened the agreement. The document promised to preserve Tibet’s political system and religious institutions. By the late 1950s, those promises had been broken through forced reforms as well as the suppression of monasteries.

When the Dalai Lama repudiated the agreement after fleeing into exile, it was not an act of rebellion. It was a response to an agreement imposed by force and violated in practice.

Why Silence Is Now Breaking

For decades, most governments avoided challenging China’s position on Tibet for strategic reasons rooted in Cold War politics. Tibet was sidelined in favour of engaging Beijing.

That position is beginning to shift. In 2024, the United States passed the Resolve Tibet Act. It states that Tibet’s status remains unresolved under international law. It rejects Chinese claims of historical finality.

The implications are broader than Tibet alone. If vague claims of “ancient ties” can justify territorial control today, then the stability of borders everywhere is at risk.

Recovering Tibet’s Lost History

The way forward is not only diplomatic—it is historical. Scholars and advocates are calling for open-archive research and international collaboration to reconnect the scattered record of Tibet’s past.

When Tibet is examined as it actually functioned—administering itself, negotiating externally, and ending imperial relationships when empires collapsed—the myth of “ancient rule” begins to unravel.

Tibet’s annexation was not inevitable. It was the result of force and political convenience. In 2026, the challenge is simple but urgent— to ensure that a historical injustice is not cemented by repetition.

The Dalai Lama’s journey to Yadong seventy-five years ago was a flight from coercion. Today’s effort to recover Tibet’s history is a flight toward truth.