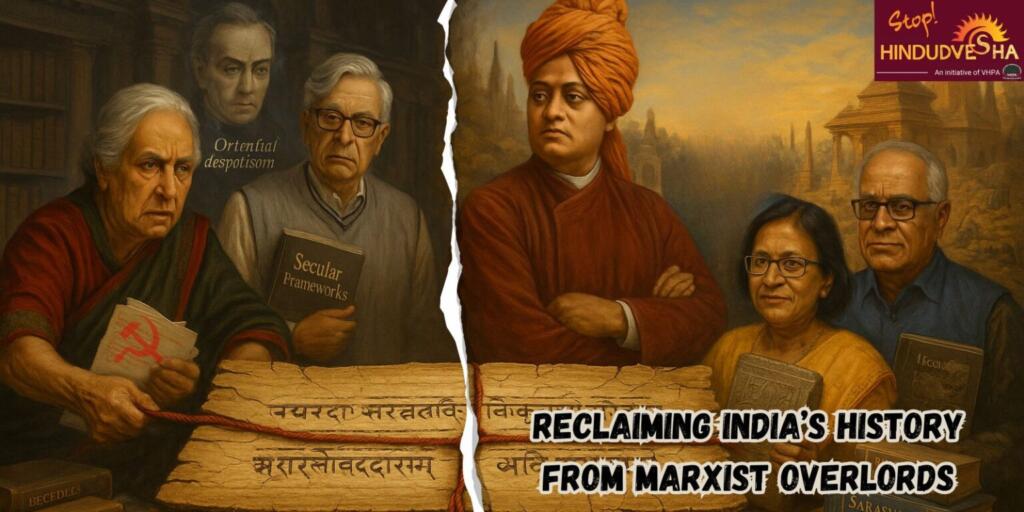

In recent years, the landscape of Indian historiography has seen the emergence of scholars who engage deeply with India’s past from perspectives that are often associated with cultural nationalism or what is broadly referred to as a Hindutva view of history. These historians argue that earlier dominant narratives, particularly those influenced by left-leaning academic traditions, have sometimes presented interpretations of India’s civilization, culture, and polity that they believe are unbalanced or dismissive of indigenous sources and contributions. As debates over history textbooks, archaeological interpretations, and cultural identity intensify, proponents of this approach emphasise academic excellence, rigorous research, and the recovery of neglected sources.

The recent social media post that asks readers to “name a few such historians these days” highlights a growing public interest in identifying scholars in Indian historiography who are conducting serious academic work aligned with these perspectives. This interest is not limited to casual observers. Educational institutions, public policy forums, and media discussions in India increasingly reflect a desire to revisit established historical narratives and broaden the range of voices included in conversations about the past. Importantly, this trend represents not just a political repositioning but an intellectual engagement with complex historical questions.

One historian frequently associated with this strand of scholarship is Ramakrishnan R. Iyer, a scholar whose work spans Indian epistemology and historiography. Though not labelled in his own work as a “Hindutva historian,” Iyer’s critiques of Eurocentric paradigms and his emphasis on indigenous modes of knowledge have made his contributions influential among those seeking alternatives to left-dominant frameworks. His writings often underscore the importance of Indian philosophical traditions, textual hermeneutics, and the need to understand historical evidence on its own cultural terms.

Another prominent name in contemporary debates is D. N. Jha, whose earlier work was seen as critiquing conventional narratives, but recent scholarship among his intellectual successors has prompted re-examination of his conclusions. Jha’s work itself was sometimes controversial, but it catalysed a broad scholarly conversation on sources and methodology and historiography that later historians continued. While Jha is not a representative of the current Hindutva side, the scholarly pushback and reinterpretations that have grown in response to his work have shaped the contours of the field.

S. N. Balagangadhara is another influential thinker frequently cited in these discussions. Though his disciplinary home is philosophy and cultural studies, his critical analysis of the methodological underpinnings of Indian history writing—especially in texts such as The Heathen in his Blindness—challenges scholars to think beyond received European frameworks. Balagangadhara’s work has inspired historians who argue for reframing Indian historiography by paying closer attention to indigenous categories of experience and social organisation.

In more explicitly historical research, scholars like Nayantara Sahgal have been mentioned in broader debates over culture and identity. While Sahgal’s work spans literature and cultural critique rather than strictly archival history, the discussions she enters into regarding national narratives show the diverse ways Indian intellectuals engage with questions of heritage, identity, and historiographical authority.

Students and observers of Indian history also point to the work of Upinder Singh, former head of the history department at the University of Delhi and author of authoritative books on ancient and early medieval India. Singh’s scholarship is grounded in meticulous engagement with archaeological evidence, inscriptions, and textual sources. While her work does not take an overt political stance, her scholarship, historiography is often valued by readers across the spectrum because of its methodological rigor and comprehensive synthesis of evidence.

Another historian often referenced in public discussions today is S. Jaishankar, India’s External Affairs Minister. Although Jaishankar is not a historian by profession, his writing on Indian civilization and foreign policy underscores the use of historical frameworks in contemporary policy thinking. His historiography and perspectives on India’s civilizational narrative and how India positions itself globally resonate with those who argue for revisiting historical interpretations that they believe have been overly shaped by colonial or Marxist paradigms.

Among emerging scholars, Sandhya Jain has attracted attention for research that foregrounds indigenous sources in reconstructing early Indian intellectual history. Jain’s work seeks to balance rigorous methods of historiography with an emphasis on primary sources that have not always received extensive scholarly focus in mainstream academic settings. Her approach exemplifies how newer historians are contributing to what they see as a necessary broadening of the field.

It is important to emphasise that characterising historians as “Hindutva side” does not mean their work lacks academic integrity. Many of these scholars engage with primary sources, inscriptions, archaeological findings, and interdisciplinary methods to build arguments grounded in evidence. The debate over historical interpretation is not unique to India. Across the world, historians regularly revisit established narratives as new evidence emerges or as new questions are posed. What distinguishes the current moment in India is the intensity of public engagement and the positioning of historical interpretation within broader cultural and political debates.

Critics of historians perceived as writing from a Hindutva perspective argue that some interpretations risk projecting contemporary political concerns onto the past or privileging certain narratives at the expense of others. Proponents, on the other hand, contend that earlier academic frameworks were unduly influenced by colonial assumptions or Marxist paradigms that did not adequately account for indigenous conceptions of polity, religion, and society. The tension of historiography between these positions fuels scholarly dialogue and has expanded the range of sources and methodologies under consideration.

Academic excellence remains central to the credibility of any historical interpretation. Peer-reviewed research, transparent methodology, and engagement with evidence are standards upheld by scholars across ideological lines. Many of the historians recognised in this context publish in academic journals, contribute to edited volumes, and participate in conferences that subject their work to critical scrutiny. This engagement with the broader scholarly community underscores that historiography remains a dynamic field of enquiry.

In conclusion, the historians often mentioned in connection with responding to left-leaning narratives through rigorous scholarship represent a diverse group. They include established academics, interdisciplinary thinkers, and emerging researchers who are committed to expanding the methodological and evidentiary basis of Indian historiography. Their work reflects an ongoing effort to revisit and rethink how India’s long and complex past is understood. As public and academic debates continue, readers and students of history are encouraged to engage with a range of perspectives, assess evidence critically, and appreciate the evolving nature of historical scholarship.