Is it okay to lose your respect and dignity under the social structure of marriage, or surrender your voice in the face of a law that often favours patriarchal norms?

Haq, currently trending on Netflix and other OTT platforms confronts this question head-on, delivering a story that feels urgent, necessary, and deeply human.

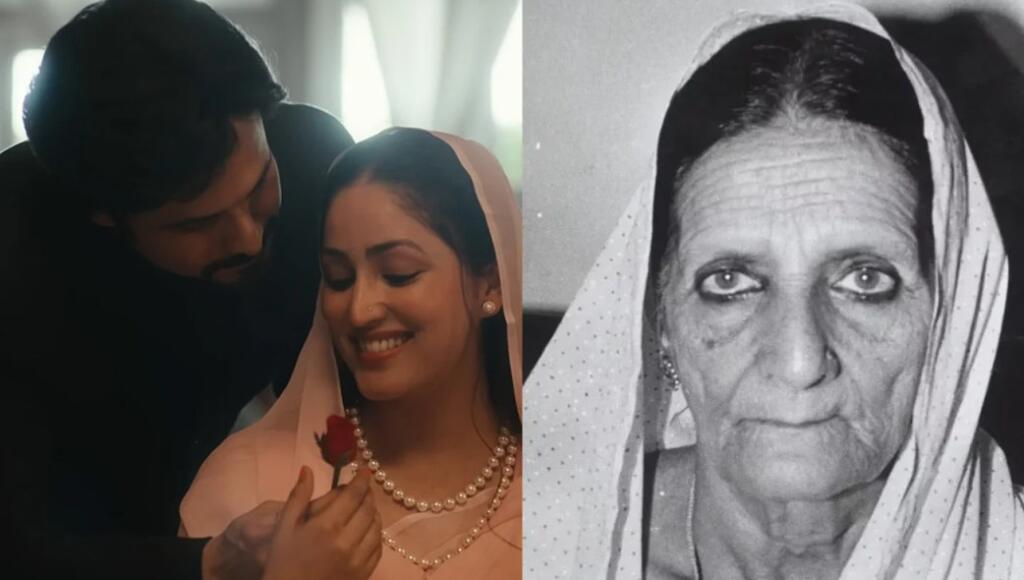

The film follows Shazia Bano (Yami Gautam), a devoted wife and mother, whose life is turned upside down when her lawyer-husband, Abbas Khan (Emraan Hashmi), divorces her in the most humiliating manner.

What begins as a personal betrayal spirals into a larger courtroom battle and ignites a national debate on faith, rights, and justice. Inspired by true events, Haq is a fictionalized and dramatized retelling of the historic Shah Bano case, chronicled in Jigna Vora’s book Bano: Bharat Ki Beti, which shook India in the 1980s and addressed the contentious issue of maintenance rights for divorced Muslim women.

Directed with clarity and conviction by Suparn S Varma, the film reminds us that deeply personal stories can echo profound social truths. Set in the 1970s and 80s, the narrative situates Shazia in Aligarh, navigating a world upended when Abbas returns from Pakistan with his second wife, Saira (Vartika Singh), and pronounces the irrevocable talaq, three words that leave her struggling for financial and emotional survival.

Supported by her steadfast father, Maulvi Basheer (Danish Husain), Shazia takes her fight to the courts, culminating in a Supreme Court showdown that transcends legal argument to highlight the struggles of countless women.

Every scene in Haq feels grounded and real. The storytelling never overcomplicates itself, nor does it descend into melodrama; it unfolds linearly, honestly, and with deep emotional resonance.

The film’s strength lies in its simplicity, anchored by Reshu Nath’s crisp and coherent writing across story, dialogue, and screenplay. The texture of Western Uttar Pradesh is captured authentically, and the dialogues are steeped in local flavour, making the world of the film immersive and immediate.

Yami Gautam delivers a career-defining performance, embodying Shazia’s pain, courage, and quiet dignity with nuance and control. Emraan Hashmi complements her with a restrained portrayal of Abbas—his anger is subtle, morally complex, and devoid of caricatured villainy.

The courtroom confrontation toward the climax, where Shazia and Abbas face the Supreme Court judges, crackles with intensity and emotional truth. Vartika Singh as Saira is pleasant but underused, while Danish Husain as Maulvi Basheer and Sheeba Chaddha as Bela, Shazia’s lawyer, bring gravitas and empathy to the ensemble.

What sets Haq apart is its refusal to be confined to a community-specific narrative. While rooted in the Muslim social context, it resonates far beyond, emerging as a story about betrayal, resilience, and hope. It is a film that gives voice to the voiceless, upholds integrity, and reminds us that the quiet, honest expression of truth can be the most potent form of protest.

In confronting the intersection of personal trauma, social expectation, and legal frameworks, Haq asks difficult questions about respect, rights, and the cost of silence, questions that remain profoundly relevant today. It is a story that moves, challenges, and stays with you long after the credits roll.

For decades, the draconian law of triple talaq had plagued the lives of countless women, leaving them financially insecure, socially ostracised, and legally vulnerable. The system often bypassed any notion of fairness or due process, reducing marriage—and the dignity of women—to a one-sided exercise of male authority. The landmark Shah Bano case in the 1980s was the first major legal challenge to this entrenched practice.

HAQ Trends in Nigeria

Haq is currently trending at No. 1 on Netflix in Nigeria, a reception that underscores the film’s universal appeal. This is because the movie is closely tied to the country’s demographic and social realities.

Nigeria has the fifth-largest Muslim population in the world, a fact highlighted by recent data from Visual Capitalist based on figures from the Pew Research Center and the CIA World Factbook.

This substantial Muslim population, spread across diverse cultural and regional contexts, includes millions of women whose everyday lives are shaped by questions of rights, justice, family structures, and social expectations—themes that HAQ places at its core.

The film’s narrative appears to resonate deeply because it reflects lived experiences that many women encounter on a daily basis, making its story feel less like distant fiction and more like a mirror of reality.

The convergence of these demographic statistics with the film’s subject matter helps explain its widespread appeal in Nigeria. It speaks directly to a large audience that sees its own struggles, silences, and resilience reflected on screen, turning HAQ into not just popular entertainment, but a point of emotional and social connection.

What Comes Out of the Film

Haq shines a light on how society often cherry-picks religious verses and twists faith to justify patriarchal norms, ignoring the core values of equality and compassion. The film also clears up common misconceptions surrounding Islamic laws and personal rights, a subject that feels particularly urgent in today’s climate.

It delves into how society routinely protects men, normalises abuse, and pressures women to adjust in the name of maintaining peace. Lines such as “Mard ka gussa hai” and “Tum sula kar lo” strike a powerful chord because they echo phrases many have heard in real life.

The dialogues emerge as one of the film’s greatest strengths. Several moments prompted spontaneous applause in the theatre, most notably when Yami Gautam’s Shazia declares, “Kabhi kabhi mohabbat kaafi nahi hoti, izzat bhi zaruri hoti hai.” This line perfectly encapsulates the essence of Haq—that love without respect is merely another form of control.

The movie reflects Shah Bano’s courage in standing up to the court in the 1980s, which remains nothing short of extraordinary. As a single mother of three, she faced not only personal betrayal and financial insecurity but also the immense weight of societal judgment in a deeply patriarchal era. Taking her plight to the legal system meant challenging entrenched norms, confronting religious misinterpretations, and speaking truth to a society that often silenced women like her.

What makes her story so compelling is not just the legal battle she fought, but the quiet defiance and resilience she embodied—turning her personal struggle into a fight for the rights of countless women left vulnerable by divorce and neglect. Shah Bano’s journey reminds us that bravery is often measured not by grand gestures, but by the courage to assert one’s dignity in the face of overwhelming opposition.

The film also explores Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) and its connection to alimony rights, tracing the landmark Shah Bano case and showing how such stories shaped real-life legal reforms. However, the dissolution of the Supreme Court’s order by then-Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, and the social fallout that followed, is relegated to a brief after-credits slide—a moment that could have benefitted from deeper exploration.

Ultimately, Haq is a steady, courageous film that does not plead for sympathy; it commands respect. It reminds viewers that standing up for your dignity is not just an act of courage—it is, quite literally, your haq.

Today, triple talaq is no longer just a customary practice; it has been criminalised under Indian law through the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019.

The law makes instant triple talaq illegal and punishable, while still allowing for the principles of divorce under Sharia to be practised in a regulated manner. What began as Shah Bano’s personal fight has evolved into a broader movement that continues to safeguard women’s rights and challenge patriarchal misuse of religious norms.