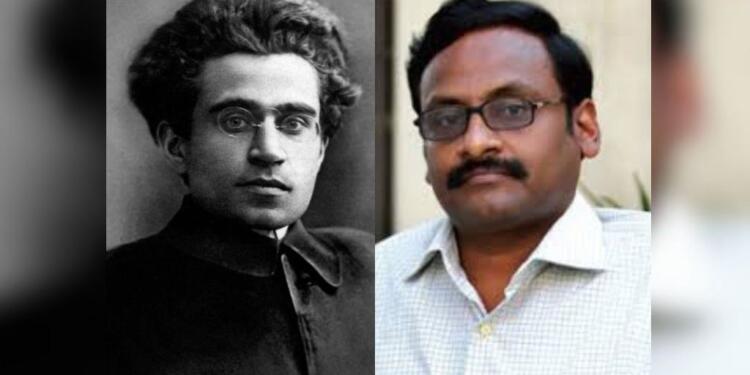

The recent article published by The Wire invoking Antonio Gramsci and G N Saibaba presents itself as a moral and intellectual intervention against state power, incarceration, and the treatment of disabled dissenters. At first glance, the piece appears compassionate and theoretically rich. Yet a closer reading reveals not rigorous analysis but a carefully curated narrative driven by ideological presuppositions. What masquerades as a defense of human dignity ultimately exposes a deeper ideological bankruptcy that substitutes polemics for reasoned engagement.

The article’s foundational move is to draw a parallel between Gramsci’s imprisonment under Italian fascism and Saibaba’s incarceration under Indian law. This comparison is emotionally potent but intellectually fragile. Gramsci was jailed by an explicitly totalitarian regime that openly sought to silence political opposition. India, for all its flaws, operates within a constitutional and judicial framework that allows appeals, reviews, and public scrutiny. To blur this distinction is not historical insight but ideological bankruptcy, because it deliberately erases context to fit a predetermined worldview.

This flattening of history allows The Wire to frame all state action as inherently oppressive and all dissent as morally pure. In doing so, the article refuses to acknowledge the complexity of modern democratic governance. Laws such as the UAPA are controversial and deserve criticism, but criticism requires engagement with evidence, procedure, and competing claims. Instead, the article treats the very existence of charges as proof of persecution. Such reasoning does not strengthen the case for civil liberties. It weakens it by turning serious debate into moral theater, a hallmark of ideological bankruptcy.

A central pillar of the piece is its rejection of reform in favor of abolition. According to The Wire, attempts to improve prison conditions or provide accommodations to disabled inmates merely legitimize an unjust system. This absolutist position may sound radical, but it is profoundly detached from lived reality. Disabled prisoners need medical access, mobility support, and humane conditions now. Dismissing reforms as morally compromised does nothing to alleviate their suffering. This posture reveals ideological bankruptcy because it prioritizes theoretical purity over tangible human relief.

The article also romanticizes dissent without interrogating its boundaries. By framing dissent as inherently virtuous and the state as inherently violent, it creates a simplistic moral binary. In the real world, societies must balance individual freedoms with collective safety. Acknowledging this tension does not amount to authoritarianism. Refusing to acknowledge it amounts to ideological bankruptcy, because it replaces ethical responsibility with ideological certainty.

Another weakness lies in the article’s heavy reliance on academic jargon and theoretical layering. Gramsci, disability studies, prison abolition, and critical legal theory are invoked in rapid succession, but rarely grounded in concrete analysis. The result is a dense rhetorical fog that shields the argument from scrutiny. When concepts are used as moral talismans rather than analytical tools, the writing ceases to persuade and begins to preach. This is yet another expression of ideological bankruptcy masquerading as intellectual sophistication.

Perhaps most troubling is how the article instrumentalizes suffering. Saibaba’s disability and hardship are invoked not primarily to demand accountability within the legal system but to advance a sweeping ideological claim against incarceration itself. Human pain becomes a means to an ideological end. This approach risks reducing individuals to symbols rather than respecting them as complex subjects whose cases deserve careful, fact based evaluation. Such instrumentalization reflects ideological bankruptcy because it treats lived experience as ammunition rather than responsibility.

In the end, The Wire presents a narrative that feels morally urgent but collapses under scrutiny. Its refusal to engage with legal nuance, its dismissal of reform, its reliance on historical false equivalence, and its preference for absolutist conclusions over hard questions all point in the same direction. What emerges is not a serious challenge to injustice but a closed ideological loop that cannot accommodate disagreement or complexity. That is the final and most damaging form of ideological bankruptcy, because it leaves readers with indignation instead of understanding and slogans instead of solutions.