The spectacle of a human being consumed by fire is an image of such visceral finality that it pierces even the most hardened armours of state censorship.

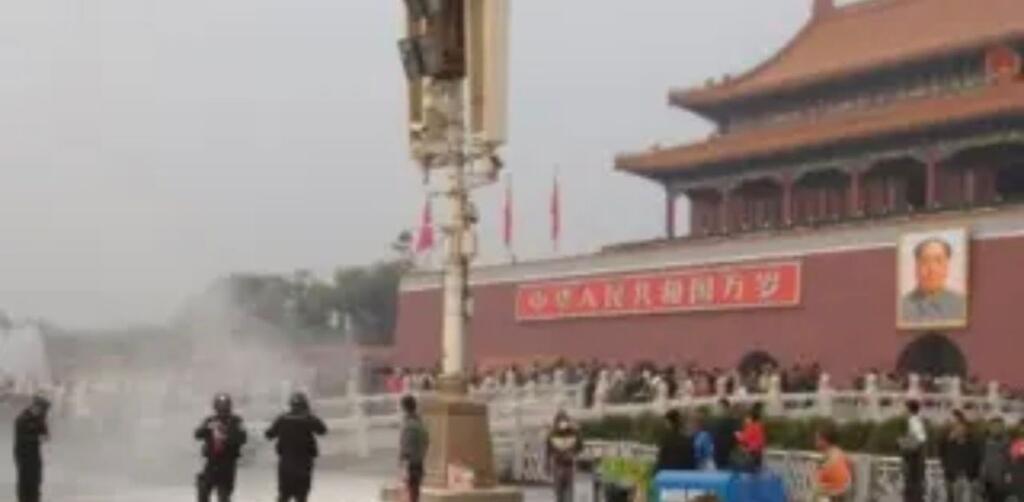

In recent days, unverified accounts and swiftly erased digital traces have circulated beyond China’s information firewalls, alleging that an individual attempted self-immolation in Tiananmen Square, the symbolic heart of the Chinese state.

Whether or not these reports can ever be conclusively substantiated, their very plausibility speaks volumes about the political reality they evoke.

The image—real or suppressed—has been enough to incinerate the lingering Western delusion that economic engagement would inevitably coax the People’s Republic towards political plurality.

This act of self-immolation, occurring under the omnipresent gaze of the surveillance state, stands not as a signal of impending revolution but as a grim testament to the total asphyxiation of hope.

On 23 January 2001, five practitioners of Falun Gong Five people set themselves on fire in Tiananmen Square in central Beijing on the eve of Chinese New Year on 23 January 2001.

That tragedy, which saw Wang Jindong and a twelve-year-old girl named Liu Siying engulfed in flames, was manipulated by the party apparatus to justify a brutal eradication campaign.

Two decades later, the regime no longer needs to manipulate the narrative because it has successfully constructed a reality where the narrative is pre-determined.

The mechanism of control has now evolved from crude propaganda to a sophisticated digital tyranny. The prompt suppression of the recent incident highlights a domestic environment where dissent is algorithmically rendered impossible.

On platforms like WeChat, the illusion of public discourse is maintained through rigged polls and curated comment sections that offer a simulacrum of engagement.

The populace, acutely aware of the invisible red lines, engages in a collective act of self-erasure. Opinions are sanitised before they are even typed, creating a sterile echo chamber where the only permissible resonance is unwavering loyalty to the core.

This is not the silence of agreement but the quiescence of survival. The digital public square has been engineered to function as a mirror that reflects only what the state desires to see, hiding the deep fractures of a society where the only honest political statement left is the destruction of one’s own body.

This model of high-tech authoritarianism is no longer contained within the borders of the Middle Kingdom. It has become a primary export commodity, packaged alongside infrastructure loans and trade deals within the Belt and Road Initiative.

Across more than one hundred and fifty nations, the architecture of the Chinese Communist Party is being replicated. From the surveillance grids of Central Asia to the internet firewalls of East Africa, the tools of suppression are being installed with the efficiency of a software update.

Beijing is not merely building roads and bridges; it is constructing a global alliance of autocracies that rely on its technology to remain in power.

The incident in Tiananmen is therefore not a local tragedy but a preview of a potential global standard, where the rights of the individual are subordinated to the security of the regime by design.

The extinguishing of liberty is perhaps most palpable in the former British colony of Hong Kong. The promise of “One Country, Two Systems,” intended to safeguard the city’s unique freedoms until 2047, has now been dismantled ahead of schedule.

The implementation of Article 23 security legislation has effectively accelerated the timeline of integration, erasing the distinction between the liberal periphery and the authoritarian core.

The vibrant civil society that once defined the harbour city has been silenced, its leaders imprisoned or exiled. The accelerated demise of Hong Kong serves as a definitive signal that the Communist Party views commitments to international treaties as temporary tactical inconveniences rather than binding obligations.

The legal strangulation of the city proves that the regime’s appetite for control is absolute and recognizes no geographic or historical exemptions.

Despite the horrific optics of burning protesters and the sullen silence of the populace, the prediction for the immediate future remains one of grim stability. Western observers often look for the breaking point, the moment when civil unrest tips into systemic collapse. However, the threshold for such a transformation will likely remain unmet by 2030.

The state has perfected the atomisation of grievance. By ensuring that no two dissatisfied citizens can organise effectively, the party prevents the coalescence of anger into a movement. The economy may falter and youth unemployment may sour the national mood, but the coercive apparatus remains loyal and effective.

The regime has insulated itself against the kind of popular uprisings that toppled dictatorships in the past by replacing the vulnerability of the human enforcer with the unblinking reliability of the machine.

In the face of this monolithic stability, the international community must identify new points of leverage. The legitimacy of the Communist Party relies heavily on domestic prestige and also the projection of global acceptance.

Major sporting events and international summits serve as a vital theatre for this projection, which offers the regime a stage to perform its fake narrative of harmony and strength.

The most potent response available to the free world is to deny Beijing this oxygen of prestige. A comprehensive boycott of all future successors to the Beijing Olympics and similar global gatherings is a necessary moral baseline.

Participating in the pageantry of a state that answers peaceful pleas with foam cannons and imprisonment is an act of complicity.

It validates the regime’s belief that its internal abuses carry no external cost. By refusing to send athletes, dignitaries, and corporate sponsors to these spectacles, the democratic world can puncture the bubble of triumphalism that Xi Jinping seeks to curate.

The fire in the square was a desperate attempt to be seen. The world honours that sacrifice not by engaging in business as usual, but by turning its back on the performative grandeur of the state that lit the match.

Until there are substantive, verifiable reforms, the seats in the VIP boxes must remain empty, leaving the regime to perform its rituals of power to a hollow audience.