Independent India promised intellectual freedom, yet some of its earliest actions contradicted that promise. Among the most troubling episodes was the removal of globally acclamied historian Dr. Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, better known as RC Majumdar from the official panel entrusted with writing the history of the national movement. This decision, taken under the watch of the Nehru government, casts a long shadow because it shows what happens when political authority attempts to control the writing of history. The episode reveals an uneasy truth. When leaders seek to define the past on their own terms and silence scholars who do not fit that preferred version, the very spirit of a democratic republic is weakened.

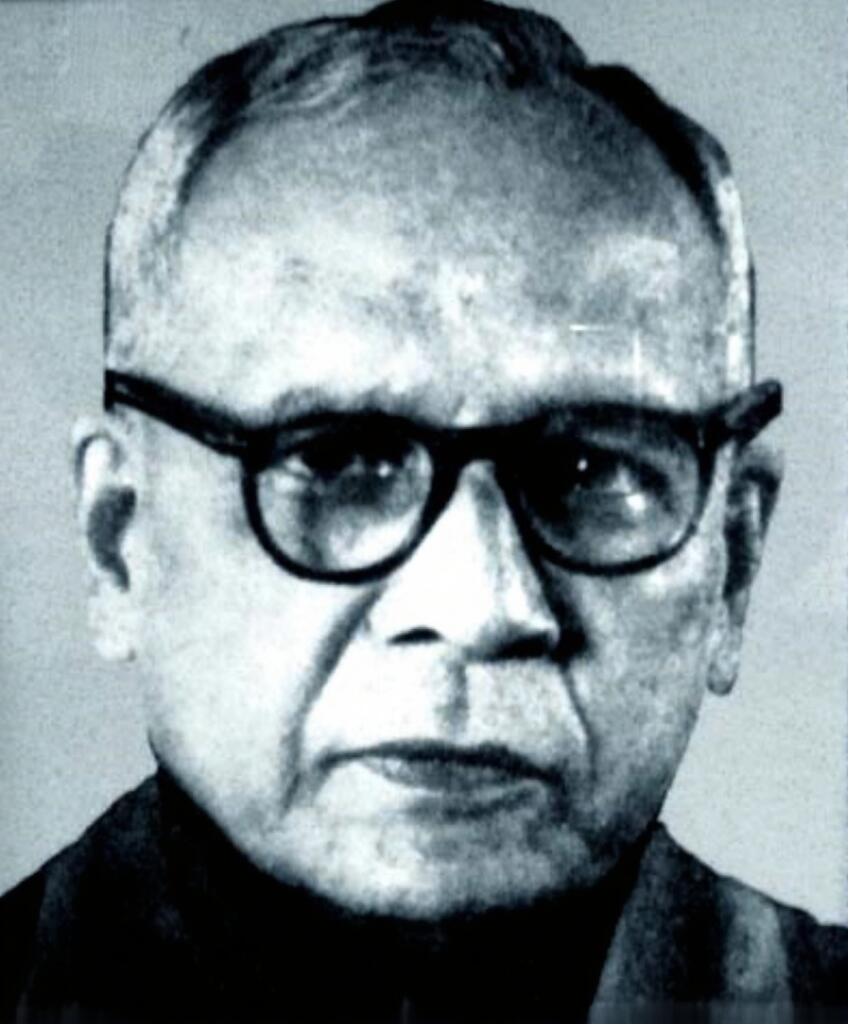

RC Majumdar was one of modern India’s most respected historians, trained in rigorous archival research and uncompromising scholarly discipline. His body of work on ancient India, the freedom movement, and the nature of political institutions reflected a commitment to evidence rather than ideology. This made him a natural choice for the government appointed panel that was to produce an authoritative multi volume history of India’s freedom struggle. Yet precisely this independence of mind soon made him inconvenient to those in power.

Majumdar’s reading of the national movement did not conform to the heroic narrative that the Nehru government preferred to foreground. He believed that the struggle for independence had many roots and many faces, including the revolutionary tradition that the state wished to minimise. He rejected the view that the movement was shaped solely by one party or one dominant leader. He also refused to portray the 1857 uprising merely as a spontaneous revolt or as a rising without national consciousness. For him, the story of Indian nationalism could not be simplified into a single stream or attributed to a single organisation.

This perspective was at odds with the political climate of the early years after independence. The new government was eager to establish a unified myth about how the nation had risen and who had guided that rise. In such a setting, a historian who insisted on portraying multiple contributors and complex motivations was seen not as a scholar but as a challenge to authority. The result was predictable. The Nehru government removed RC Majumdar from the official historican panel when he refused to adjust his findings to suit the desired narrative.

This action revealed a deeper conflict. It was not simply a matter of one scholar and one government. It was an early test of whether the republic would allow intellectual diversity or whether the state would demand conformity in the sphere of history. By dismissing Majumdar, the government signalled that history was to be curated rather than investigated. The crux of the issue is that political convenience was allowed to override academic integrity.

Majumdar’s response to his removal further highlighted this conflict. Rather than retreat, he dedicated himself to producing his own multivolume account of the freedom movement. It was a monumental project, completed without state support, driven by his belief that truth should not depend on political approval. His work documented aspects of the struggle that official narratives tended to ignore, including the contributions of revolutionaries, regional movements, and ideological groups that were at odds with the mainstream interpretation. His scholarship proved that history thrives when it is written freely, without fear of offending the powerful.

The Nehru government’s decision had lasting consequences. Once the precedence was set that the state could guide historical interpretation, future political leaderships discovered that they too could attempt to shape the past to legitimize their present. The removal of Majumdar thus became one of the earliest examples of political influence over academic history in independent India. It was a moment when the principles of free inquiry came into conflict with the preferences of those in office, and the latter prevailed.

The episode also showed the gap between proclaimed values and practiced values. The early leadership of India spoke often about liberty, openness of thought, and scientific temper. Yet when confronted with a historian who applied scientific temper to subjects that did not align with the official view, the state chose authority over openness. The treatment of RC Majumdar exposed the vulnerability of intellectual freedom in a new nation still insecure about its identity and narrative.

The legacy of this clash has not faded. Today, scholars and students continue to debate the event because it illustrates a timeless problem faced by many societies. When a government attempts to fix a single story of the past, it risks weakening the foundations of democratic culture. Nations grow stronger when they allow multiple interpretations, disagreements, and revisions. They grow brittle when they allow a single interpretation to become enforced consensus. Majumdar’s removal stands as a reminder that the health of a democracy can be measured by how it treats its historians.

It is also a reminder that the writing of history is not merely an academic exercise. It shapes the consciousness of future generations. It influences what children learn about their nation, what citizens believe about their shared past, and how political leaders justify their decisions. When this power is controlled by the state, and when inconvenient scholars are sidelined, the past becomes a tool rather than a field of honest inquiry. The Nehru government’s handling of RC Majumdar is therefore more than a personal slight. It is an illustration of how political authority can compromise the sincerity of national memory.

In the end, Majumdar’s refusal to bend his scholarship stands taller than the decision to exclude him. His dedication to truth over political comfort has earned him a lasting place in India’s intellectual history. His removal, on the other hand, remains a cautionary tale about the dangers of letting governments dictate the past.

The conflict between RC Majumdar and the Nehru government thus remains profoundly relevant. It warns that when political authority controls the narrative of history, it risks diminishing the intellectual courage that every democracy needs. It warns that the past should be explored, not controlled. And above all, it warns that nations must protect their historians if they hope to protect their own integrity.