The Battle of Rezang La, fought on the icy ridges of the southeastern Chushul Valley on 18 November 1962, has long stood as one of the most extraordinary testaments to raw human grit in modern military history. It was not a story of superior firepower or better preparation; in fact, the Indian troops of the Charlie Company, 13 Kumaon, faced overwhelming disadvantages. Yet their stand that night fighting literally to the last man and the last round cemented Rezang La as a symbol of unmatched courage.

Despite being heavily outnumbered and poorly equipped for the harsh winter conditions, the 120 soldiers of the company managed to hold back repeated Chinese assaults. By dawn, 114 Indian soldiers were dead. But before they fell, they inflicted more than 1,000 casualties on the enemy, a figure that remains staggering given the scale of their disadvantages.

A Battle Fought Against Nature, Numbers, and Limitations

The challenges began with nature itself. Rezang La, located at an altitude of around 16,420 feet, was a battleground where temperatures could drop to minus 30 degrees Celsius. Soldiers struggled even to dig defensive positions in the frozen ground. Colonel N. N. Bhatia (retd.) later wrote that the mountain’s high crests prevented Indian artillery shells from reaching enemy targets, denying the company much-needed fire support. Anti-personnel mines were few, automated digging tools were largely absent, and outdated World War II–era .303 bolt-action rifles had to serve where modern weaponry was badly needed.

Adding to the difficulty were the old 62 radio sets whose batteries froze in the bitter cold, often leaving platoons completely cut off from each other and from higher command. In contrast, Chinese troops possessed 7.62 mm self-loading rifles and included many fighters from the Singkiang region who were naturally acclimatised to the high-altitude terrain. They also carried out detailed reconnaissance, spreading maps and studying the landscape before launching their assaults.

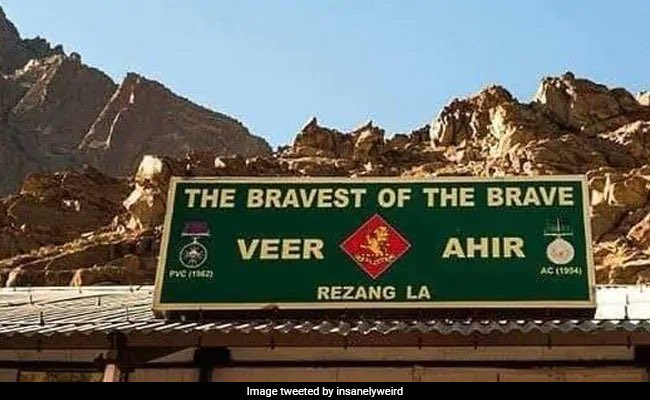

In the face of all this, the soldiers of Charlie Company almost all of them Ahirs from Gurgaon and the Mewat region of Haryana displayed extraordinary strength. Apart from their commander, they were young men from communities of farmers and cattle-keepers, many of whom had experienced little active combat beyond postings in Jammu and Kashmir. For them, this was the first time battling the unforgiving elements of the high Himalayas.

The remarkable courage of these men has long set the Charlie Company apart. As author Kulpreet Yadav notes in The Battle of Rezang La, no other Indian Army company has ever earned as many honours from a single engagement. In total, they received one Param Vir Chakra, eight Vir Chakras, four Sena Medals, and one Mention-in-Dispatches.

Despite being almost entirely wiped out, their resistance prevented the Chinese from capturing Chushul. The surviving elements of 13 Kumaon regrouped, and with the support of the 114 Brigade, managed to hold the valley. Just three days later, on 21 November, the Chinese declared a unilateral ceasefire.

Looking back, many historians and military commentators have wondered what could have been possible had these soldiers been better supported. Yadav himself writes, “What if these brave soldiers had better guns, more ammunition, adequate snow clothing, full stomach food, artillery support and able leaders at the army headquarters and in the government?” Even without those advantages, they produced one of the most extraordinary last stands in Indian military history.

Major Shaitan Singh: The Heart of the Defence

No recounting of Rezang La can overlook the leadership of Major Shaitan Singh, the officer commanding Charlie Company and posthumous recipient of the Param Vir Chakra. As wave after wave of Chinese troops attacked, Major Singh moved from post to post, personally encouraging his men, directing fire, and rallying platoons that had been cut off by the terrain and the chaos of battle.

His presence came at enormous personal risk. He was first wounded in the arm and later struck in the abdomen.

Two soldiers dragged him behind a boulder to shield him from further fire, but he insisted on continuing to direct the battle until he succumbed to his injuries. Months later, when an Indian search party reached Rezang La in February 1963, they discovered his frozen body still near the same boulder surrounded by the remains of his men, many of whom were found in fighting positions, clutching their rifles even in death.

His body was brought to Jodhpur and cremated with full military honours, his leadership forever etched into the memory of the Indian Armed Forces.

Five soldiers from the company were taken prisoner by Chinese forces. Among them was Naib Subedar Ram Chander, a platoon commander who regained consciousness only in captivity. He spent six months as a prisoner of war before being released.

One of the most unusual stories from the aftermath of the battle involved Havaldar Nihal Singh, who managed to escape from Chinese custody only a day after being captured. In an interview many years later, he recalled how the guards became distracted, enabling him to slip away under the cover of darkness.

When he had walked roughly 500 metres, his captors fired three shots into the air, but he kept moving.

Exhausted, injured, and bleeding from both hands, Nihal Singh wandered the frozen terrain. It was then, according to his recollection, that he encountered a scruffy dog. This dog, which soldiers of the Charlie Company had fed weeks earlier, seemed to recognise him. It began walking in a particular direction, and Singh followed.

After several hours, the animal led him directly to battalion headquarters. Some later wondered whether he may have been hallucinating under the strain of his injuries and the cold, but Singh remained convinced the dog had saved his life.