On April 8, 1929, Delhi’s Hindustan Times broke routine to publish a rare evening edition, while The Statesman in Calcutta rushed its report to London to slip past colonial censors.

Newsrooms crackled with urgency that afternoon as two young revolutionaries had tossed low-intensity but thunderous bombs into the Central Assembly Hall—today’s Parliament while ringing the chamber with cries of ‘Inquilab Zindabad! and Samrajyavad ka Nash Ho!’

As red pamphlets titled “To Make the Deaf Hear” fluttered through the smoky air, reporters scrambled for details. By nightfall, newspapers across India and abroad were blazing with dramatic headlines with one international daily even saying “Reds Storm the Assembly!”

The men behind the uproar were Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt. Following the incident, both were tried and convicted.

While Bhagat Singh went to become one of the most iconic figures of the Indian freedom struggle, his comrade Dutt gradually faded from public memory, remembered only occasionally, rarely honoured with the dignity he deserved.

Early Sparks of Patriotism

Batukeshwar Dutta, also known as BK Dutta, Battu, and Mohan — was a son of Goshtha Bihari Dutta. He was born on 18 November, 1910, in Onari, Khandaghosh village, Purba Bardhaman district in West Bengal into a Bengali kayastha family.

He graduated from Pandit Prithi Nath High School in Kanpur. He was a close associate of freedom fighters such as Chandra Shekhar Azad and Bhagat Singh, the latter of whom he met in Cawnpore in 1924.

Batukeshwar learned about bomb making while working for the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA).

Dutt’s patriotism took root early while still a schoolboy in Kanpur. He used to secretly slipped anti-British leaflets, distributed by Ramakrishna Mission workers into students’ bags. By the time he reached his teens, the fire of resistance was already burning bright.

A Chance Meeting That Forged a Legend

Dutt first met Bhagat Singh through revolutionary Suresh Chandra Bhattacharya in Kanpur. The meeting nearly took a disastrous turn. Seeing a young stranger approach, Bhagat Singh mistook him for a police spy and prepared to attack before Bhattacharya rushed in to introduce them.

That moment marked the beginning of a bond so deep that Bhagat Singh later learned Bengali from Dutt and, with his help, read the works of Karl Marx. Their friendship would soon take them into the heart of one of India’s most storied revolutionary acts.

The Assembly Bombing: A Rumble to Wake the Deaf

To protest the draconian Public Safety Bill and Trade Disputes Bill, the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association decided to ignite the nation’s conscience—not with bloodshed, but with sound.

On 8 April 1929, Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt entered the Central Assembly after surveying it two days earlier. Wearing a hat to conceal his identity, Bhagat Singh lobbed the first low-intensity bomb deliberately away from the members’ benches. In the ensuing confusion, Dutt threw the second.

The chamber plunged into darkness and panic, but the two young men did not flee. They stood firm, shouting “Inquilab Zindabad!” and scattering leaflets quoting French revolutionary Auguste Vaillant, “To make the deaf hear, a loud noise is required.”

Their arrest was dramatic, their courage electrifying. Within days, they had become heroes of the youth, forcing the British to hold court proceedings inside jail to control the crowds. Both were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Sorrow of Not Sharing The Gallows

When Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru were later sentenced to death in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, Dutt felt a deep sorrow, he regretted not receiving the same fate alongside his friend.

Hearing of this, Bhagat Singh wrote him a letter from jail, comforting him with the warmth of a comrade and a brother.

Dutt’s own health deteriorated in prison, and in 1938 he was released on the condition that he would not engage in violent activity.

But the freedom struggle had become his identity. He joined the Quit India Movement in 1942 and was jailed again.

Independence—and the Unexpected Cruelty of Freedom

When India finally achieved freedom, luxury did not wait for its revolutionaries. Instead, Batukeshwar Dutt stepped into a life of hardship.

To survive, he worked as a cigarette company agent, sold cigarettes himself, and even became a tourist guide. His wife, Anjali, took up a job as a schoolteacher.

A failed attempt to run a bakery exhausted their meagre resources.

Once, while applying for a bus permit, Dutt was asked for proof that he was truly a freedom fighter—an insult that stung him so deeply he tore up his application on the spot.

President Rajendra Prasad later intervened to grant him the permit, but by then the wound had already been made.

A Final Wish: To Rest Beside a Friend

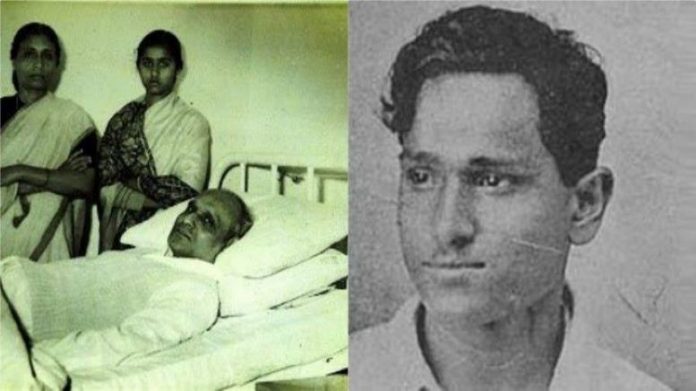

As Batukeshwar Dutt’s health declined, he was admitted to AIIMS.

When Punjab’s Chief Minister Ram Kishan visited him and asked if he had any last wish, Dutt’s eyes filled with tears.

He said softly, “I wish only to be buried beside my friend Bhagat Singh.”

Bhagat Singh’s mother, Vidyavati, considered Dutt her own son and often cradled his head in her lap at the hospital.

Honoring his final desire, his body was taken to Hussainiwala, near the India-Pakistan border—the resting place of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev.

There, beside his brothers in sacrifice, Batukeshwar Dutt received his final salute.

Why We Must Remember Him

India is what it is today because thousands like Batukeshwar Dutt chose a life of danger, struggle, and anonymity over comfort and safety.

The least we can do now is ensure that these heroes never fade into the background of our national memory.

To remember Dutt is to honor the countless unnamed revolutionaries who gave up everything so that we could breathe freely.