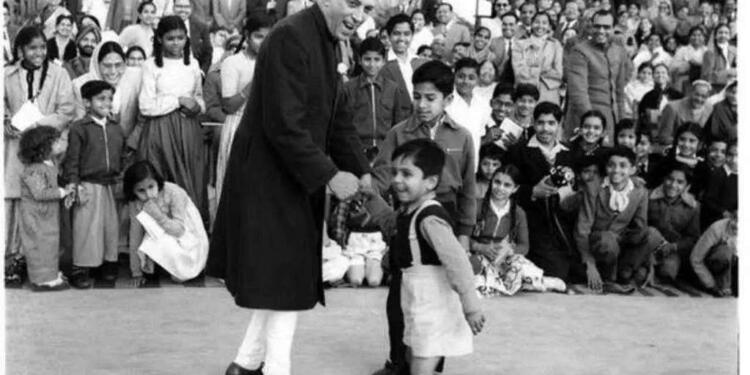

For decades, Indians have grown up believing a sweet, sanitised tale that Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru “loved children,” that they fondly called him Chacha Nehru, and that November 14 became Children’s Day after his death to honour his affection for the young. But archival records, newspaper reports, and forgotten editorials reveal a very different history one that directly contradicts the popular myth.

Children’s Day was not declared after Nehru’s death in 1964. It was created by Nehru himself, in 1955, while he was Prime Minister. And its purpose had little to do with children’s welfare. Instead, it emerged as a carefully choreographed propaganda event designed to impress two visiting Soviet leaders Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev and to present Nehru as a mass idol adored by Indian children.

In November 1955, Delhi witnessed an unprecedented spectacle. Schools were instructed to prepare thousands of children for rallies, marches, and displays that would coincide with Nehru’s birthday celebrations. The visiting Soviet delegation, accustomed to grand public demonstrations and personality cults, was the intended audience.

Multiple archived reports show that the government machinery worked overtime to create an image for the Soviets: Nehru as a leader worshipped by the young, a democratic alternative to the Soviet cult of leaders like Lenin and Stalin.

Thus, the first “Children’s Day” was not a spontaneous tribute from the nation. It was a state-orchestrated event crafted to elevate Nehru’s image on an international stage. In a hard-hitting editorial, senior journalist K.R. Malkani drew uncomfortable parallels between Nehru’s celebrations and authoritarian propaganda used in Europe, especially Hitler’s “Hitler Jugend.”

The editorial noted that for three weeks, Delhi’s education system had been effectively paralysed as children were repeatedly rehearsed for choreographed birthday events. The piece observed:

School schedules were disrupted

Children were compelled to participate in political rallies

The entire exercise resembled state-driven personality worship

The editorial went further, suggesting that a culturally meaningful day for Children’s Day would have been Krishna Janmashtami, celebrating Bala Krishna — “the greatest child of all time.” But such culturally grounded suggestions were ignored, overshadowed by Nehru’s own image-building drive.

The following year confirmed that this was no one-time experiment.

On November 14, 1956, The Times of India reported:

“Nearly 100,000 children assembled at the National Stadium today to participate in a Children’s Day rally, which coincided with the Prime Minister’s 67th birthday celebrations.”

The line is revealing. The “rally for children” was nothing more than a mass mobilisation aligned with Nehru’s birthday a replication of Soviet-style shows of strength and affection.

This tradition grew rapidly, eventually crystalising into a permanent annual observance. Over time, official narratives shifted away from the uncomfortable origins and instead focused exclusively on Nehru’s supposed deep affection for children.

Ironically, Nehru himself had warned in Discovery of India about “invisible colonialism” the takeover of society by subtle, narrative-driven forces. Yet, the 1955–56 Children’s Day events illustrate how the ruling elite sought to implant their own narrative into India’s cultural landscape through political theatrics rather than genuine sentiment.

For nearly seventy years, the official narrative has conveniently ignored how Children’s Day actually began. Textbooks, children’s speeches, school functions, and government advertisements have all repeated the same myth that the people of India chose Nehru’s birth anniversary out of national admiration.

In truth, the date was chosen by Nehru himself, staged as part of Cold War-era optics, and continued by the political establishment long after. What began as a PR event was converted into unquestioned tradition.

Children’s Day should celebrate childhood not political personality cults. It should reflect India’s culture, traditions, and values not the propaganda tactics borrowed from Soviet-style rallies.

The long-hidden truth is now clear: Nehru declared his own birthday as Children’s Day for political theatrics, not because children demanded it or the nation voluntarily chose it.

As new generations seek a more honest understanding of history, it is time to shift the narrative from image-building to genuine child welfare. India must reclaim Children’s Day from myth, return it to meaning, and base it on facts rather than folklore.