Art has always been a battleground between uncomfortable truth and ideological convenience. The newly launched trailer of Dhurandar is no exception. Within hours of its release, a familiar chorus began—critics, Lefts in particular, branding it as “violent,” “divisive,” or “propaganda.” The loudest objections often come from the same camp that once romanticized political movements soaked in blood but now trembles when brutality is portrayed on screen in a way that defies their approved narratives.

The Fear of Uneasy Truth

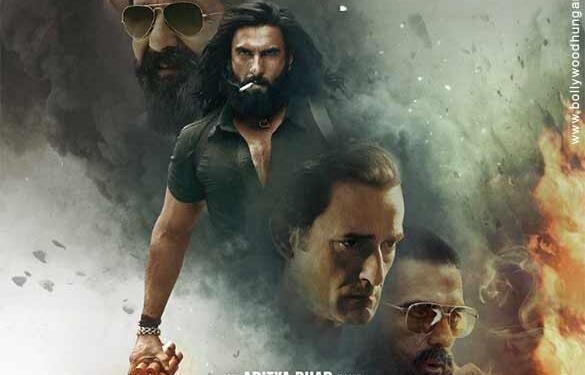

The Dhurandar trailer delivers visual shocks, yes—but those moments are not imaginary. They resurrect fragments of real history, stories most citizens have forgotten or never been taught. The film delves into the chilling account of Pakistani militant operations in Kashmir and pays special attention to the case of Captain Saurabh Kalia, whose torture in 1999 remains one of India’s most haunting wartime memories.

Yet, for many on the left, such depictions are “too graphic.” Their argument is not that these things never happened but that showing them “provokes hatred.” This logic reveals a deep moral confusion. When films or books showcase terrorism or aggression against Indians, the discomfort should not be directed toward the filmmaker—it should be directed toward those who committed the violence.

A Lesson the Left Can’t Digest

What unsettles critics is not the sword, the gun, or the explosion, but the mirror these stories hold up. For years, selective outrage has shaped India’s public discourse. When films explore state excesses or depict insurgents as victims, they are hailed as bold and necessary. But when a movie like Dhurandar exposes the victims of terrorism—soldiers, villagers, families—the tone shifts. Suddenly, freedom of expression becomes a matter of “responsibility,” and depictions of raw brutality are called “dangerous.”

This intellectual inconsistency stems from a larger unwillingness to confront ideologically inconvenient truths. Violence seen through one lens is revolutionary; through another, it becomes fascist. The audience is wiser than this hypocrisy. Most Indians know that war and insurgency are ugly, but refusing to portray that ugliness doesn’t make it disappear.

When the Villain is Historical, Not Fictional

The trailer of Dhurandar introduces Ilyas Kashmiri, portrayed by Arjun Rampal, a character inspired by real-world figures associated with cross-border militancy. This portrayal doesn’t glorify violence—it exposes it. To claim that showing a beheading scene promotes brutality is as naive as saying a film about the Holocaust promotes genocide. Portraying horror is not the same as endorsing it; it is an act of remembrance.

It is worth recalling that people like Musharraf once celebrated men behind such crimes as “national heroes.” That reality, however uncomfortable, is part of history. Pretending it didn’t happen because it makes some factions nervous is intellectual cowardice.

The Forgotten Horror of Saurabh Kalia

Captain Kalia’s story is not fiction. Captured during the Kargil War, he was brutally tortured before his death. His case is among the most disturbing examples of human rights violations committed against Indian soldiers. Yet, despite years of appeals, the international community largely turned a blind eye.

By revisiting his sacrifice on screen, Dhurandar challenges viewers to look at what war really costs—not in political speeches or slogans but in human suffering. Labeling such portrayal as “violence-mongering” is not only dismissive of the artist’s intention but an insult to the memory of real victims.

Artistic Freedom Cannot Be Selective

The recurring theme in these leftist objections is control—control over what can be shown, said, or remembered. But democracy cannot function if artistic freedom is filtered through ideological approval. The same groups that champion “freedom of speech” during controversies involving films like Udta Punjab or Lipstick Under My Burkha suddenly find censorship virtuous when a nationalist filmmaker ruffles their sentiments.

True freedom of expression is consistent. It must allow uncomfortable truths from all sides, not just from those who speak the language of intellectual trendiness.

Violence vs. Depiction of Violence

There is a moral distinction between glorifying and documenting violence. Dhurandar appears to fall squarely in the latter category. By confronting brutal episodes without sanitization, it denies the audience the luxury of moral distance. That discomfort is exactly what meaningful cinema should provoke.

Condemning films like this on grounds of “excessive violence” ironically protects real perpetrators from public scrutiny. A society that refuses to look at its own wounds risks forgetting who inflicted them.

Hypocrisy and the Comfort of Silence

When left-leaning commentators object to such films, they often claim to defend harmony or avoid communal tension. But peace built on silence is fragile. Honest storytelling—especially when it reveals atrocities against Indians—doesn’t create tension; it exposes the tension that already exists, hidden beneath selective amnesia.

The discomfort isn’t about the movie causing hatred; it’s about it dismantling long-held myths that certain ideologies have carefully cultivated.

A Wake-up Call for Intellectual Fairness

Dhurandar may well be a flawed film, like any piece of art. But dismissing it because it challenges a particular ideological comfort zone reveals the inherent bias that still dominates cultural criticism. The moral of the story is not that one side holds a monopoly on truth but that truth itself must remain visible, however harsh or inconvenient.

A mature society must allow all its stories to be told—not just the ones that flatter its self-image. Films like Dhurandar force us to remember that human rights, nationalism, and artistic freedom are not separate conversations. They intersect in ways that define what kind of nation we wish to be.

The real test of any film lies not in the noise it generates online but in how audiences interpret it. If Dhurandar offends some sensibilities, that discomfort should spark debate, not censorship. The left’s anxiety about “violence” on screen reflects their fear of losing narrative control, not a genuine concern for social harmony.

India’s democracy was built on disagreement, not uniformity. Let every artist speak and every audience judge. Truth does not need ideological approval—it only needs courage to be told.