Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s recent statement “Sindh may return to India someday… borders can change” has triggered a wave of political and strategic debate across the region. But this remark did not emerge in a vacuum. It comes at a moment when India has conducted one of its most powerful tri-service military exercises since Operation Sindoor, and at a time when Pakistan has been expanding its military infrastructure around the sensitive Sir Creek region. When seen together, these developments make Singh’s words more than just a civilisational reference they amount to a calibrated strategic warning to Pakistan. The message is unmistakable: India is watching, India is prepared, and India has not forgotten what Sindh the land of the Indus means to its civilisation, its people, and its long-term strategic imagination.

Civilisational Sindh and the Defence Minister’s Warning

At a cultural event, Rajnath Singh spoke about Sindh not merely as a geographical region but as an inseparable part of India’s ancient civilisational framework. He reminded the audience that Sindh, although on the other side of the border today, remains eternally tied to India through history, culture, language, and faith. The Sindhi community in India especially those from the generation of leaders like Lal Krishna Advani has never emotionally accepted the forced separation of Sindh during the 1947 Partition. He emphasised that even many Muslims in Sindh considered the waters of the Indus as sacred as the Aab-e-Zamzam, reflecting the deep civilisational unity that transcended political boundaries.

When Rajnath Singh said, “Borders can change… who knows, tomorrow Sindh may return to India,” he invoked not only historical memory but also geopolitical reality. His remark was symbolic, yet it was also layered with contemporary strategic meaning especially because he delivered it at a time when tensions around Sir Creek have escalated and India has been conducting powerful military drills along the western frontier.

His message was not merely a cultural reflection. It was a reminder that borders are not immutable, and any country that attempts adventurism against India should be aware that historical geography can shift again this time in India’s favour.

Exercise Trishul: India’s Planned Demonstration of Force Post–Operation Sindoor

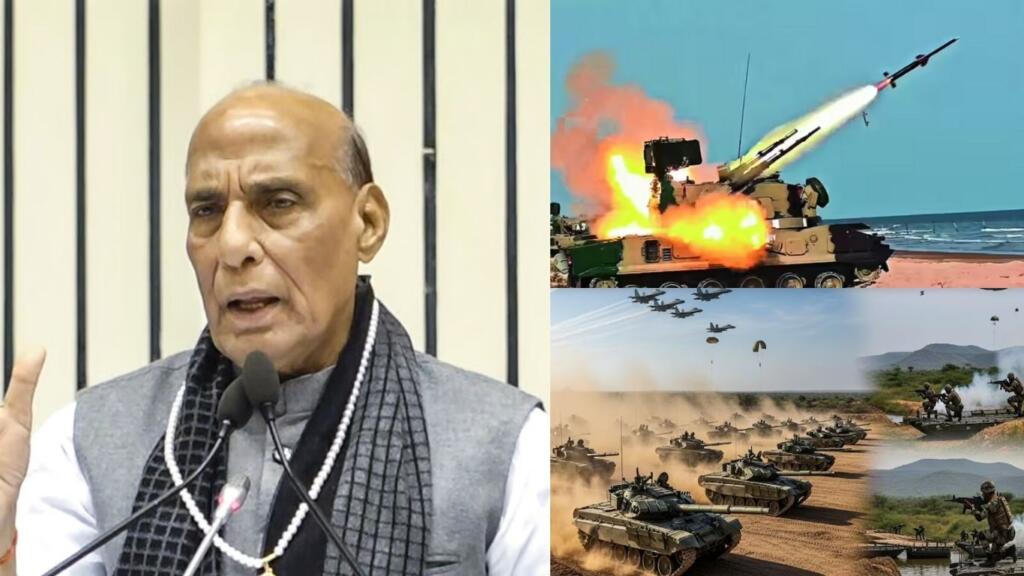

Just days before Rajnath Singh’s Sindh reference, India concluded a major 12-day tri-service war drill Exercise Trishul across Gujarat and Rajasthan. This was India’s first major simulated conflict exercise since Operation Sindoor, the decisive and hard-hitting May 2025 engagement with Pakistan that left several Pakistani military installations severely damaged.

Exercise Trishul was not a routine drill. It brought together the Army, Navy, and Air Force to practice coordinated offensive and defensive operations in a post-Sindoor environment. The Indian Air Force deployed Rafales, Sukhoi Su-30MKIs, and unmanned platforms for simulated deep strikes into southern Pakistan. The Army tested its T-90 tanks, BrahMos missile regiments, and Akash air defence systems systems that had proven their reliability by neutralising Pakistan’s projectile barrages during Operation Sindoor. The Navy participated with warships and coastal surveillance units to strengthen jointness across the western theatre.

The chosen theatre of exercise particularly the Kutch region was not accidental. This area remains one of the most sensitive flashpoints in the India–Pakistan border dynamic, especially due to its proximity to Sir Creek. Trishul was designed not only to sharpen readiness but also to send a clear signal: India is fully prepared to respond to any Pakistani misadventure and, if necessary, resume where Operation Sindoor left off.

In this context, Rajnath Singh’s remark that borders may change becomes far more than rhetoric. It becomes a strategic reminder placed within the framework of Indian military readiness.

The Sir Creek region barely 96 kilometres long is one of the least-discussed but most strategically significant stretches on the India–Pakistan boundary. It lies between Gujarat’s Rann of Kutch and Pakistan’s Sindh province. Although narrow and marshy, its location and access to the Arabian Sea make it a region of immense military and economic relevance. Pakistan has increasingly been attempting to alter ground realities here by expanding bunkers, radars, and forward operating bases capable of launching drone attacks, amphibious operations, or naval infiltrations.

Rajnath Singh, in recent weeks, not only acknowledged these developments but issued an unequivocal warning to Pakistan. He noted that Pakistan’s illegal construction activities in Sir Creek reflect an attempt to slowly shift the tactical balance. If Pakistan dares to intrude into Indian territory, he declared, India’s response would change the “history and geography” of the region.

This is not an empty threat. During the 1965 war, the Indian Army demonstrated its ability to push deep into the region. Today, with significantly superior technology, surveillance, and strike capabilities, India’s military options are even more robust. Singh’s mention of Karachi barely 200 to 300 kilometres from Sir Creek was a direct hint that India will not limit any retaliation to just localised responses. Should Pakistan escalate, India may choose to target deeper military infrastructure, something that became evident in Operation Sindoor as well.

The recent unannounced visit by Pakistan Navy chief Admiral Naveed Ashraf to forward posts in Sir Creek has only added to Delhi’s concerns. His statement promising to protect every inch of Pakistan’s maritime borders indicates Islamabad’s nervousness after Trishul and after Rajnath Singh’s comments. India has taken note and has signalled its readiness.

Sindh, Sir Creek, and the Strategic Future

When Rajnath Singh speaks of Sindh returning someday, it is not merely a cultural sentiment it is a layered geopolitical message. It links civilisational memory with present-day military preparedness. It reminds Pakistan that India has both the historical legitimacy and the contemporary capability to reshape borders if pushed beyond limits. Exercise Trishul reinforced this message through hard military power, showcasing India’s readiness across land, air, and sea. And the Sir Creek tensions reveal exactly why Rajnath Singh chose this moment to speak of borders changing.

Pakistan’s attempts to create new facts on the ground, coupled with its military posturing near Sir Creek, have been noticed. India’s message is unmistakable: it is prepared, it is strong, and it will retaliate decisively if provoked. If Pakistan attempts adventurism, the consequences both in geography and history may indeed be far greater than it imagines.