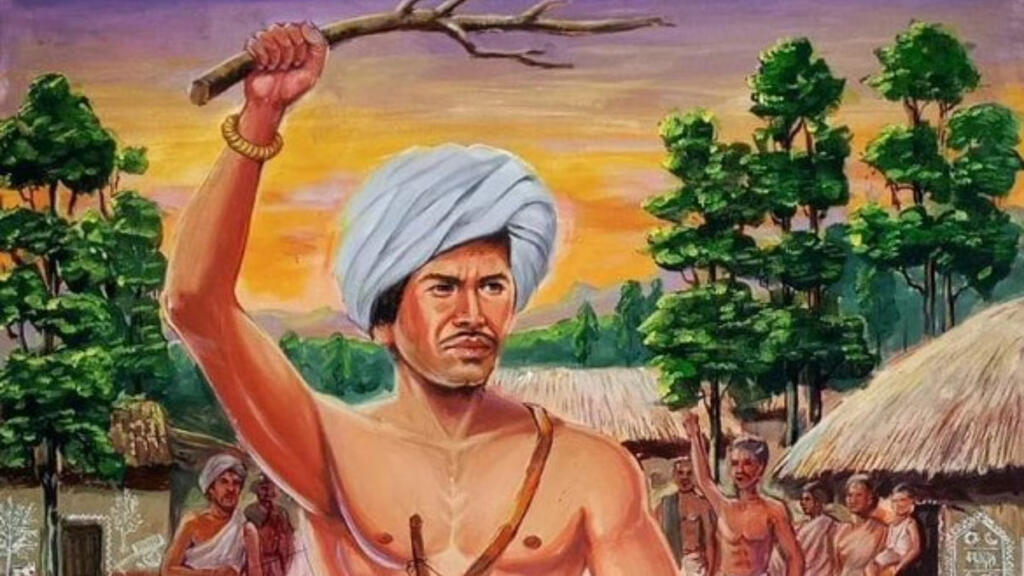

As India observes Janjatiya Gaurav Divas on November 15, the nation once again turns its attention to the extraordinary legacy of Bhagwan Birsa Munda, one of the greatest tribal freedom fighters in Indian history. Marking his 150th birth anniversary, the Centre’s decision to commemorate this day as Janjatiya Gaurav Diwas and expand it into a week-long celebration honours not just a revolutionary leader but an entire civilisational chapter often neglected by mainstream historians.

Birsa Munda lived only 25 years, yet in those brief years he emerged as a formidable force who shook the British Empire, inspired lakhs of tribals across eastern and central India, and fundamentally altered the trajectory of anti-colonial tribal movements. His leadership terrified not just the British Raj but also the Christian missionaries, whose systematic attempts to convert tribal communities met fierce resistance under his leadership.

Birsa was not merely a rebel he became a symbol of indigenous identity, a socio-religious reformer, a spiritual leader, and a warrior whose “Ulgulan” (Great Tumult) changed the course of tribal rights in India.

Born on 15 November 1875 in Ulihatu (present-day Jharkhand), Birsa Munda grew up amidst poverty but within a culturally vibrant tribal environment. Economic hardship pushed the family to move frequently, and the young Birsa sought education wherever possible. In this quest, he converted to Christianity and briefly became Birsa David to study in a missionary school.

However, his time with missionaries exposed him to a new reality. The aggressive efforts of missionary groups to dismantle tribal culture, impose new religious practices, and belittle indigenous beliefs deeply disturbed him. Alongside this, British agrarian policies were tearing apart the traditional socio-economic fabric of tribal life.

Between 1886 and 1890, Birsa lived in Chaibasa then the nerve centre of tribal discontent against British exploitation. By the age of 15, he had witnessed the scale of land alienation, cultural humiliation, and social fragmentation inflicted by British rule and missionary interference.

By 1890, Birsa was no longer a student he was a politically awakened young man preparing for an ideological and armed confrontation.

For centuries, the Munda tribe followed the Khuntkatti system, a traditional form of joint land ownership passed down within clans. British rule systematically destroyed this structure. The introduction of the Zamindari system which encouraged non-tribal outsiders (Dikus) to settle, buy land, and exploit labour reduced proud tribal landowners to bonded labourers on their own soil.

To the Mundas, this wasn’t merely economic exploitation. It was an existential threat. Their land was not just property it was identity, ancestry, and spirituality.

This widespread dispossession triggered one of India’s most remarkable tribal uprisings. In 1894, Birsa Munda declared Ulgulan, calling for an end to British rule and the expulsion of Dikus from tribal lands. His charisma and moral authority earned him the title “Birsa Bhagwan”, as thousands from the Munda, Oraon, and Kharia communities rallied behind him.

Simultaneously, Birsa founded his own religious movement. Declaring himself a messenger of God, he rejected missionary domination and revived indigenous spirituality. His followers saw in him not just a political leader but a divine reformer who liberated them from religious subordination.

Birsa Munda’s spiritual movement proved to be a greater nightmare for Christian missionaries than even his armed revolt. His teachings revived tribal identity, discouraged conversion, and undercut missionary authority. While missionaries levied taxes and tightly controlled converts, Birsa offered dignity without coercion.

His message was simple yet revolutionary:

Return to your roots. Honour your land. Reject the cultural invasion.

Birsa travelled from village to village, awakening masses with a blend of faith and resistance. He urged people to give up meat, adopt prayer, stay united, and assert their rights. His movement attracted not just tribals but also some Hindus and Muslims who saw in him a powerful spiritual figure.

Alarmed by his influence, the British arrested him in 1895, hoping to crush the uprising. But after his release in 1897, Birsa returned with even greater resolve. He went underground, built a disciplined guerrilla force, and began preparing for a massive confrontation.

On December 24, 1899, Birsa launched his decisive attack. His guerrilla fighters targeted police stations, government outposts, and churches symbols of British authority and missionary penetration. Several policemen were killed, and the rebellion spread swiftly through the Chotanagpur region.

For nearly two years, Birsa’s forces engaged in guerrilla warfare, taking over swathes of territory, disrupting colonial logistics, and inspiring tribal groups across neighbouring regions.

But the British retaliated with brutal force machine guns, mass arrests, village burnings. Hundreds of tribals were massacred in cold blood. Birsa and his troops retreated into the dense forests and hills of Singhbhum, continuing the resistance.

On 3 February 1900, Birsa was finally captured from the Jamkopai forest in Chakradharpur. He was imprisoned in Ranchi jail, where he died on 9 June 1900, reportedly of cholera though many believe he was poisoned.

He was just 25.

Though the British crushed the rebellion, they were forced to recognise the fundamental injustice that triggered it. Birsa’s movement directly led to the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act of 1908, a historic law that protected tribal land rights, restricted land transfers to non-tribals, and restored “Khuntkatti” ownership.

Even today 119 years after his death Birsa Munda remains a towering icon of indigenous assertion, anti-colonial nationalism, and cultural pride. While left-leaning Marxist historiography has often sidelined his role to fit ideological narratives, the people of India have never forgotten him.

Birsa’s life was short, but his fire reshaped India’s tribal resistance.

His name endures as a symbol of defiance, dignity, and indigenous identity a legend who challenged an empire and rekindled a civilisation’s self-respect.