Bihar witnessed a major surge in voter turnout during the first phase of its Assembly elections, with data released by the Election Commission of India (ECI) showing 64.66% polling across 121 constituencies as of 8:30 p.m. on Thursday. The figure marks a sharp increase compared to both the 2020 Assembly and 2024 Lok Sabha elections and stands out as the highest turnout recorded in the state since 2010.

Turnout Surges After Years of Stagnation

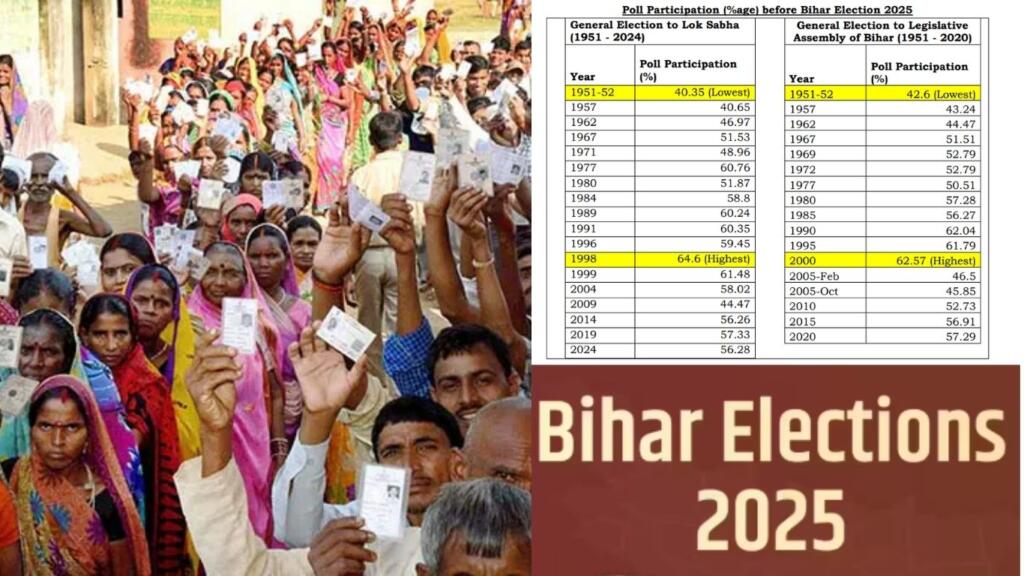

Bihar’s voter turnout has shown large fluctuations over the past two decades. In 2005, only around 45–46% of voters participated, a figure that rose to 52.6% in 2010 and further to 56.8% in 2015. The 2020 Assembly elections and the 2024 Lok Sabha polls both hovered around 57%. Thursday’s polling, therefore, represents the first major upswing in a decade.

For more than ten years, Bihar’s turnout had stagnated near 57%, reflecting persistent voter disengagement despite consistent improvements in electoral infrastructure and awareness campaigns. During the 2024 general elections, Bihar registered the lowest voter turnout in the country just 56.4%, nearly ten percentage points below the national average. The last time the state crossed the 60% mark was in the 2000 Assembly elections, when turnout reached 62.5%.

The latest data indicates a clear reversal of that long-term trend. The turnout in the 121 Assembly constituencies that went to polls in the first phase is 9.3 and 8.8 percentage points higher than the figures recorded in these same constituencies during the 2024 Lok Sabha and 2020 Assembly elections, respectively.

While the increase in voter turnout is being seen as an encouraging sign of renewed civic participation, it has also drawn attention because it follows a significant reduction in the number of registered electors after the Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls.

Between the electoral rolls used for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections and the final rolls released after the SIR, Bihar saw a net deletion of 3.07 million electors a 4% reduction in the total number of registered voters across the state. Within the 121 constituencies that went to polls on Thursday, deletions amounted to 1.53 million voters or 3.9% of the roll compared to the 2024 Lok Sabha data.

Despite this large-scale cleanup, the latest polling data suggests that the process did not suppress actual voter participation. The ECI listed a total of 37.51 million registered electors for these 121 constituencies, a slight 0.4% increase over the 37.37 million figure in the final SIR roll. Out of these, 24.3 million electors cast their votes, compared to 21.55 million who voted in the same constituencies during the 2024 general elections.

SIR Deletions Did Not Affect Actual Voters?

The numbers reveal a crucial insight, the SIR process, rather than disenfranchising legitimate voters, appears to have removed largely inactive or duplicate entries from the rolls. The data clearly shows that the number of people who actually voted increased significantly, even though the total electorate grew only marginally.

Looking at historical trends strengthens this conclusion. Between the 2010 and 2015 Assembly elections, the number of electors in these 121 constituencies increased by 21.7%, while the number of voters increased by 30.5%. Between 2015 and 2020, both electors and voters rose at nearly the same pace 9.2% and 9.5%, respectively.

In contrast, during the 2025 Assembly election, voter turnout increased by 17.1%, while the number of electors rose by just 1.1%. This means that the rise in actual voters was consistent with historical growth rates, even though the size of the electorate expanded much more slowly.

This pattern supports the argument that the SIR did not eliminate genuine voters from the rolls. Instead, it largely targeted voters who were either registered in multiple locations, had migrated, or had not participated in elections for years.

The increase in turnout, despite a smaller overall electorate, provides evidence that the SIR improved the accuracy of Bihar’s voter rolls without restricting participation. The logic here says, when the rolls reflect a more accurate and current list of residents, the turnout percentage naturally increases because the denominator total electors better represents actual, active voters.

In effect, the SIR ensured that Bihar’s voter lists were streamlined, leading to a more realistic measure of engagement. This outcome directly challenges the assumption that large-scale deletions automatically suppress voting. Instead, Bihar’s experience shows that an updated roll can coexist with, and even encourage, higher voter participation.

Analysts who examined the draft SIR electoral roll data released on August 1 had already pointed out this possibility, noting that many deletions appeared to be linked to outdated or duplicated entries. The subsequent rise in voter turnout now provides empirical support for that observation.

While exact verification is impossible since the ECI does not publish individual voter identities the trend is unmistakable. Bihar 2025 turnout surge demonstrates that the SIR exercise has not led to an absolute decline in voting participation. Instead, it appears to have strengthened electoral credibility by eliminating ghost entries and reducing duplication.

Historically, Bihar has ranked among the lowest turnout states, which means a substantial portion of its pre-SIR rolls may have included non-active voters. The current election, therefore, offers a case study in how systematic electoral roll cleansing can improve both the integrity and effectiveness of democratic participation.