It is on this same day on 21 November 1962, the month-long India – China war came to an end when Beijing announced a unilateral ceasefire, just as abruptly as it had launched the conflict. For India, the war remains one of the most defining and painful episodes in its post-Independence history a moment that reshaped military planning, diplomatic strategy, and national security attitudes for generations.

The conflict unfolded at a time when India and China were seen as two newly independent, socialist-oriented nations attempting to carve out an Asian model of cooperation. They had signed the Panchsheel Agreement in 1954, pledging mutual respect and peaceful coexistence. With the Cold War intensifying globally, India positioned itself as a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, hoping China would join hands as a fellow Asian power seeking strategic autonomy.

However, beneath these diplomatic niceties, Beijing pursued a very different course. As India extended friendship and political trust, China strengthened its grip on disputed territories, particularly Aksai Chin, even constructing a strategic road linking Tibet and Xinjiang. What followed in 1962 is widely remembered in India as a grave breach of trust a war many Indians perceived as China’s “betrayal” of the spirit of Panchsheel and regional cooperation.

More than six decades later, the memory of the conflict continues to influence India’s military posture and foreign policy instincts. From border management to defence preparedness, the lessons of 1962 still echo strongly. Below is a detailed account of the betrayal India perceived, the events that led to the conflict, and the military failures that contributed to one of the most challenging periods in independent India’s history.

The Sudden Offensive: A Conflict India Never Expected

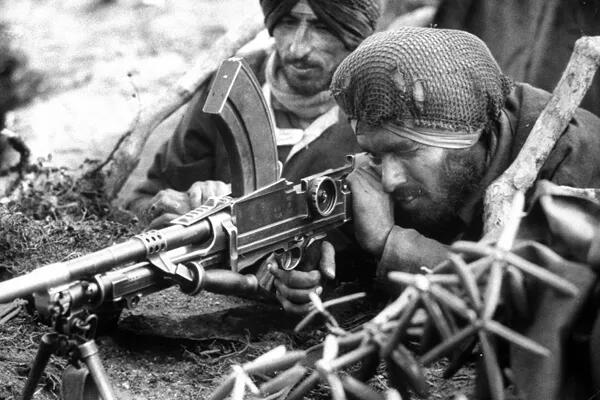

China launched a full-scale offensive on 20 October 1962, targeting both the eastern sector (Arunachal Pradesh, then NEFA) and Ladakh. The scale and speed of the attack stunned India. Despite rising tensions in previous years, Indian leadership believed China would avoid war. The first blow came when Indian positions along the Namka Chu river near Tawang were overrun within hours.

The war lasted roughly a month, culminating in the Chinese ceasefire declaration on 21 November. With this announcement, China claimed victory and withdraw to pre-war lines in most sectors, although it retained control over Aksai Chin. The unilateral ceasefire mirrored the unilateral aggression with which the conflict had begun, reinforcing India’s sense of betrayal.

Broken Promises: Panchsheel and the Road to Conflict

The Panchsheel Agreement, meant to be the foundation of peaceful relations, collapsed under the weight of conflicting territorial claims and China’s unilateral actions. India had trusted China’s assurances, while Beijing quietly strengthened its position through strategic military and infrastructural moves.

One of the clearest signs of divergence emerged in the mid-1950s, when India discovered that China had built a highway through Aksai Chin — a region India considered its territory. At the time, India was committed to the principles of peace, global neutrality, and diplomatic restraint. China, however, viewed territorial consolidation as essential to its national security strategy.

This gap in expectations widened after India granted asylum to the Dalai Lama following the 1959 Tibetan uprising. China viewed India’s gesture as political interference, while India saw it as a humanitarian act consistent with its global image. The two nations drifted further apart, with China accusing India of undermining its authority in Tibet, and India hoping that the dispute could be resolved diplomatically.

During and after the conflict, both sides sought to shape international understanding of the war. China portrayed itself as a victim of Indian provocation, alleging that Indian patrols had crossed into Chinese territory. It argued that India had refused to accept “reality” in Aksai Chin and parts of NEFA.

India, meanwhile, consistently called for dialogue and peaceful settlement. Its stand was reinforced by support from major world powers. Despite global Cold War divisions, both the United States and the Soviet Union viewed China’s attack as an unjustified act of aggression.

China’s narrative did not substantially shift international opinion. Instead, the world largely sympathized with India, reinforcing the perception that Beijing had violated the spirit of Panchsheel and Asian solidarity.

The Strategic and Psychological Impact on India

The 1962 war was a profound shock for India. It exposed weaknesses in military preparedness, leadership structure, and strategic planning. India had adhered to a defensive posture rooted in diplomacy and trust, while China had prepared for a rapid, high-altitude military campaign.

The defeat forced India to overhaul its defence policies. It triggered a major shift in military planning, leading to expanded defence budgets, modernization of equipment, and stronger international partnerships. In the decades that followed, India strengthened its presence along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), raised specialized mountain divisions, and improved infrastructure in border areas a gradual reversal of the vulnerabilities that existed in 1962.

The war also reshaped political thinking. India’s earlier assumption that Asian solidarity and peaceful dialogue would prevail gave way to a more cautious and security-centered approach in dealing with China.

In addition to the geopolitical context, the outcome of the war was heavily influenced by failures in India’s military command structure. Contemporary analyses and later accounts by military officers point to significant errors in strategic judgment, logistical planning, and leadership.

The Indian Army was constrained by inadequate equipment, limited resources, and poor infrastructure in the border regions. However, the deeper issues lay in the chain of command and the political-military decision-making process.

In the late 1950s, the responsibility for managing the Himalayan frontier shifted from the Ministry of External Affairs to the Home Ministry, which directed an aggressive “Forward Policy.” Indian troops were instructed to establish small, isolated posts close to claimed boundaries, even in logistically unsustainable terrain.

The assumption repeated at the highest levels was that “China will not attack.” This belief filtered down the chain of command, weakening military preparedness and situational awareness.

Several senior officers raised concerns about the Forward Policy and the deployment of vulnerable positions. Yet these concerns were often overlooked or suppressed. For example:

• Lt Gen S.P.P. Thorat, who had predicted Chinese maneuvers in a 1959 internal assessment, was passed over for promotion.

• Lt Gen B.M. Kaul, despite lacking operational credentials, rose rapidly due to political patronage and was placed in key leadership roles.

• Brigadier J.P. Dalvi, author of Himalayan Blunder, later acknowledged the impossibility of the tasks assigned to his brigade.

In the eastern sector, Indian troops were positioned along the Namka Chu river an exposed and indefensible location dominated by Chinese forces on higher ground. Orders to clear the Thag La ridge placed the brigade in a situation where survival itself became difficult once Chinese forces attacked on 17 October.

The Chinese offensive destroyed India’s 7 Infantry Brigade in hours. By 22 October, Tawang had fallen. After a brief tactical pause, fighting resumed on 17 November, leading to the destruction of 4 Infantry Division and the fall of Se La and Bomdi La. The road to Assam lay open. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s emotional message “our hearts go out to the people of Assam” reflected the gravity of the situation.

China’s ceasefire on 21 November halted further advances. The unilateral declaration ended what many consider one of the gravest crises in India’s military history.

Lessons from 1962

Political favoritism and bureaucratic interference weakened the chain of command. Decisions were sometimes driven by individual ambitions or political alignment rather than operational readiness.

China had built extensive infrastructure in Tibet and Xinjiang, enabling quick troop movements. India lacked comparable logistics, supply lines, and mobility.

Repeated warnings from experienced officers were overlooked. Strategic advice from individuals like Lt Gen Thorat and Gen Thimayya was dismissed.

Indian brigades were often placed in positions that did not allow for effective defence or manoeuvre. In contrast, Chinese forces exploited terrain advantages skillfully.

Interestingly, while the eastern front saw a collapse, the Ladakh sector held more effectively under Brigadier T.N. Raina, demonstrating that leadership quality significantly influenced outcomes even in adverse conditions.

Sixty-two years later, the reverberations of 1962 continue to shape India–China relations. Border tensions have persisted, culminating in events such as the Galwan Valley clash in 2020, which resulted in casualties on both sides and led to a severe breakdown in bilateral trust.

India has since expanded border infrastructure, improved surveillance, and strengthened alliances, including deeper strategic partnerships with countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

The war also inspired India to invest more intensely in its understanding of Chinese military doctrine, strategic culture, and geopolitical ambitions. Analysts repeatedly emphasize the need to study Chinese language, history, and military writings to better anticipate shifts in Beijing’s strategy.

The War That Redefined India’s Strategic Outlook

The 1962 war remains a turning point in India’s national security narrative. It underscored the dangers of misplaced trust, the consequences of inadequate preparation, and the importance of independent strategic assessments.

The conflict revealed weaknesses in India’s defence structure but also ignited reforms that would transform the military in subsequent decades. It taught India that diplomacy must be matched with preparedness, and goodwill must be balanced with vigilance.

Today, as India navigates an evolving geopolitical landscape and an assertive China, the lessons of 1962 remain profoundly relevant. The war may have ended on 21 November 1962, but its impact endures guiding India’s military modernization, shaping its foreign policy, and reminding policymakers of the enduring need for strong, competent leadership in safeguarding national security.