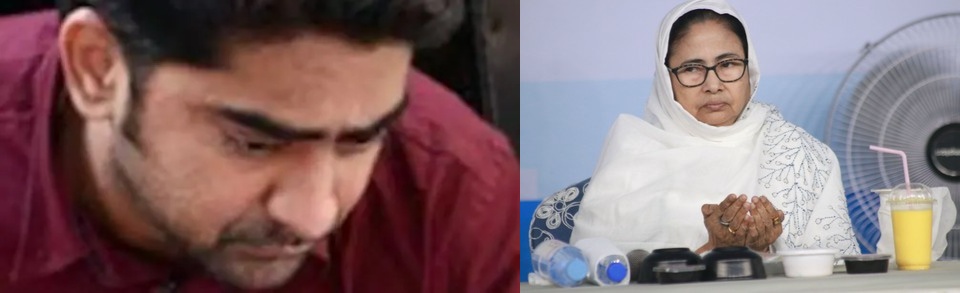

The latest case from Kolkata has once again exposed the grim reality of safety of women in West Bengal. In a shocking incident at the Hyatt Regency in Bidhannagar, Naser Khan—convicted in the infamous 2012 Park Street gangrape case—was accused of molesting and assaulting a woman during the early hours of October 26. The alleged attack took place inside a five-star hotel, symbolizing not only individual failure of law enforcement but also the larger collapse of justice and accountability, women protection in particular, under Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s rule.

According to the police complaint, Khan, along with his nephew Junaid Khan, physically assaulted a woman and her companions after picking a fight at the Playboy Club inside the hotel. What followed was nothing short of terror: bottles were hurled, doors locked, and the woman molested by a group of men while she frantically tried to seek police help. Despite the FIR and availability of CCTV footage, no arrests have been made—a familiar pattern in Bengal’s handling of crimes against women.

A Repeat Offender Protected by Weak Governance

The name Naser Khan evokes grim memories of another horrific crime: the gangrape of Suzette Jordan, a 40-year-old Anglo-Indian mother of two, inside a moving car in Park Street in 2012. Convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison, Khan was released prematurely for so-called “good behaviour,” displaying the shocking leniency extended to violent offenders in the state. His reappearance in yet another crime underscores how systemic negligence and political apathy have allowed predators to roam free. It’s a tight slap on Mamata Banerjee’s rule.

The question that demands an answer is simple—why was a convicted rapist roaming the streets of Kolkata instead of completing his full sentence? Under a government that claims to stand for “women empowerment,” the contradiction is glaring.

Rising Sexual Violence, Declining Accountability

West Bengal’s crime statistics over the past decade paint a disturbing picture. Reports of sexual violence have surged despite Mamata Banerjee’s rule or having a woman Chief Minister at the helm. Instead of tightening enforcement or ensuring justice for victims, Mamata Banerjee and her party colleagues have often resorted to dismissive rhetoric or outright victim blaming, women in particular.

Take the recent Durgapur case, where a second-year medical student from Odisha was gangraped on October 10. Rather than focusing on the culprits, Banerjee publicly shifted blame onto the victim, remarking that “women should not go out at night” and “must protect themselves.” This line of thinking not only trivializes the trauma of survivors but also perpetuates a regressive mindset that excuses male violence.

Unfortunately, such comments are not isolated. In 2012, when the Park Street gangrape case first made headlines, Banerjee herself called it a “fabricated story” meant to malign her government—a stance later disproven in court. This history of denial and deflection has created an atmosphere where offenders feel protected and victims feel abandoned.

A Culture of Political Patronage and Fear

The recurring involvement of individuals with alleged ties to political power structures complicates justice further. In many localities across Bengal, complaints against perpetrators affiliated with the ruling party are either diluted or ignored. This nexus between crime and politics has deeply undermined women’s faith in the legal system.

In Haridevpur, for instance, a young woman was reportedly raped by a Trinamool Congress worker and his associate after being invited to a birthday celebration. The victim was held captive overnight, raising echoes of unchecked brutality seen in previous cases. A month later, a female student was gangraped inside the South Calcutta Law College campus. Each crime adds another layer of fear and resignation among women who now think twice before approaching the police.

Even hospitals—spaces meant for healing—have turned nightmarish. The brutal rape and murder of a postgraduate trainee doctor at RG Kar Medical College in 2024 remains one of the darkest stains on the state’s conscience. Despite protests from doctors and civil society, Mamata Banerjee’s administration initially dismissed the outrage as politically motivated, further eroding trust.

When the State Turns Its Back

The central failure of the Mamata Banerjee government to proetct women lies not only in rising crime rates but in its consistent apathy. Each case reveals an administrative machinery more focused on image management than justice. Victims’ statements, evidence, and medical reports frequently lead nowhere due to delayed investigations or the protection of influential accused.

Civil society groups and opposition voices have repeatedly demanded judicial oversight into cases of sexual violence, citing rampant police inaction. Yet, the Chief Minister’s response has been defensive at best and accusatory at worst. This growing trust deficit has left women in Bengal feeling unprotected, forcing many to believe that safety is a privilege, not a right.

The Way Forward

The state urgently requires structural reform—starting with depoliticizing its police apparatus and ensuring swift prosecution of sexual crimes. Victim support systems need strengthening, conviction rates must improve, and the government must be held accountable for early releases that embolden serial offenders.

More importantly, the leadership must abandon its culture of denial. A true commitment to safety of women begins with empathy and acknowledgment—not excuses. Every time a politician blames a woman for her assault, it legitimizes violence and signals to predators that impunity reigns.

West Bengal was once known for its progressive ideals and social consciousness. Today, however, it has become a cautionary tale of how governance failures, partisan politics, and moral hypocrisy can collectively destroy the sanctity of justice. The recent incident involving Naser Khan is not just another case—it is the symptom of a decaying system where women are unsafe even in the heart of the state capital under the watch of a government led by a woman.

Until accountability replaces complacency, the women of Bengal will continue to live under the shadow of fear.