Born on October 30, 1909, into an affluent Parsi family in Bombay, Homi Jehangir Bhabha’s life journey remains one of India’s most remarkable tales of intellect, vision, and national service. A man of science, art, and strategy, Bhabha not only led India into the atomic age but also established the very institutions that continue to shape its scientific and technological prowess. Known globally as the Father of India’s Nuclear Programme, his story is one of brilliance, perseverance, and patriotism.

Early Life and Education: A Scholar Who Defied Expectations

Bhabha’s early years were marked by privilege and promise. Educated at Bombay’s Cathedral and John Connon School, he displayed extraordinary brilliance from a young age. At just 15, he entered Elphinstone College after passing his Senior Cambridge Examination with Honours.

Coming from a family that included industrial luminaries such as Dorabji Tata and Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, Bhabha was expected to follow a conventional path into engineering. His father, Jehangir Hormusji Bhabha, a distinguished lawyer, wanted his son to study mechanical engineering at Cambridge and later work for Tata Steel in Jamshedpur.

However, Cambridge exposed the young Homi Bhabha to the magnetic world of physics. His fascination with atomic particles and radiation grew rapidly. When he expressed his desire to switch to physics, his father reluctantly agreed on one condition: that he first secure a first-class degree in mechanical sciences. Bhabha did precisely that, passing with flying colours in 1930.

He then pursued a doctorate in theoretical physics at Cambridge under the mentorship of Paul Dirac and worked at the famed Cavendish Laboratory. During his studentship, he divided his time between Cambridge and Niels Bohr’s institute in Copenhagen, publishing several groundbreaking papers, including The Absorption of Cosmic Radiation in 1933, which earned him the prestigious Isaac Newton Studentship.

World War II and the Birth of India’s Atomic Vision

In September 1939, while visiting India, World War II broke out. Unable to return to Europe, Bhabha began working at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru under Nobel Laureate C.V. Raman. This unexpected turn of events became the foundation of India’s atomic revolution.

Bhabha soon recognised the potential of nuclear energy for both peace and progress. He passionately advocated for its peaceful use and warned against its destructive misuse on global platforms. His deep scientific insight, combined with his sense of national duty, led him to write a letter to the Tata Trust in 1944, proposing the establishment of a research institute dedicated to fundamental physics.

This vision materialised as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in 1945, which became the nucleus of India’s scientific research ecosystem. It was followed by the Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay (AEET), later renamed Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) after his death.

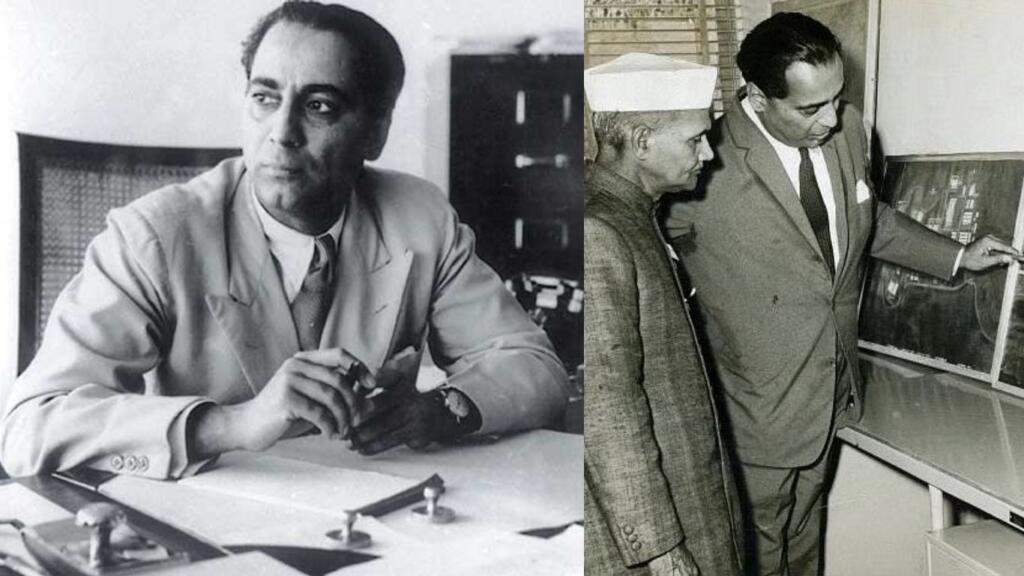

Bhabha’s charisma and intellect also won the trust of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, to whom he wrote in 1948 suggesting the creation of a powerful, small, and autonomous body to oversee atomic energy development. Nehru agreed, appointing Bhabha as the first chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) that same year.

India’s Nuclear Strategy: Thorium and Self-Reliance

Unlike many Western scientists, Bhabha looked beyond uranium-based energy models. He devised a three-stage nuclear power programme centred on thorium, a resource found in abundance in India. His goal was not just atomic energy but strategic autonomy ensuring India’s nuclear independence from foreign influence.

His forward-thinking approach made India one of the few countries to pursue thorium technology, setting the groundwork for long-term self-reliance in the energy sector. He emphasised the dual purpose of nuclear research for peaceful development and national defence and consistently underscored the importance of indigenous capability.

Bhabha’s leadership also extended to diplomacy. In 1955, he presided over the United Nations Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy in Geneva, where his stature as a scientist-statesman was evident. Three years later, in 1958, he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

His achievements were recognised at home when he received the Padma Bhushan in 1954.

A Multifaceted Genius: Artist, Scientist, and Patriot

Beyond science, Bhabha was a man of refined taste. He loved classical music, painting, and architecture, and collected artworks from around the world. His residence, Mehrangir, in Mumbai’s Malabar Hill, reflected his eclectic interests. He believed that art and science were two expressions of human creativity, and both inspired his sense of innovation.

Despite his refined lifestyle, Bhabha remained deeply rooted in national service. He saw India’s nuclear ambitions not as symbols of aggression but as emblems of sovereignty and strength. His close relationship with Nehru and later with Lal Bahadur Shastri ensured that India’s atomic programme had both political support and strategic direction.

However, his untimely death in a tragic plane crash on January 24, 1966, near Mont Blanc in Switzerland, left the nation in shock. Bhabha was travelling to Vienna to attend a conference when Air India Flight 101 crashed, killing all on board. His loss came just 18 days after he had claimed that India could develop a nuclear bomb within three months a statement that later fuelled conspiracy theories.

The CIA Theory and the Shadow of Suspicion

Decades after his death, rumours persisted that Dr Bhabha’s plane crash was no accident. A controversial 2008 book, Conversations with the Crow, claimed that a CIA officer had admitted to orchestrating the crash to halt India’s nuclear progress. The theory was based on America’s discomfort with non-Western nations developing atomic capabilities.

The alleged conversation suggested that the United States, already alarmed by China’s 1964 nuclear test, was wary of India becoming another atomic power. Although no conclusive evidence supports these claims, the coincidence of Bhabha’s and Shastri’s mysterious deaths in 1966 added fuel to the speculation.

Regardless of these theories, the fact remains that Homi Bhabha’s vision had already taken root his institutions continued to thrive, and India’s nuclear journey was unstoppable.

Dr Homi Jehangir Bhabha was more than a nuclear physicist; he was a nation-builder, an artist, and a visionary. His foresight gave India not just atomic power but scientific confidence. The Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, TIFR, and Department of Atomic Energy stand as living tributes to his genius.

His legacy influenced generations of scientists, including Dr Vikram Sarabhai and Dr A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, who carried forward his dream of self-reliant science and technology.

On his birth anniversary, India remembers not just the man who dreamt of splitting the atom, but the patriot who united a nation through science. As Bhabha once said, “No nation could be truly great unless it was self-reliant in science and technology.” That dream of a strong, self-reliant, and secure India remains his greatest gift to the nation