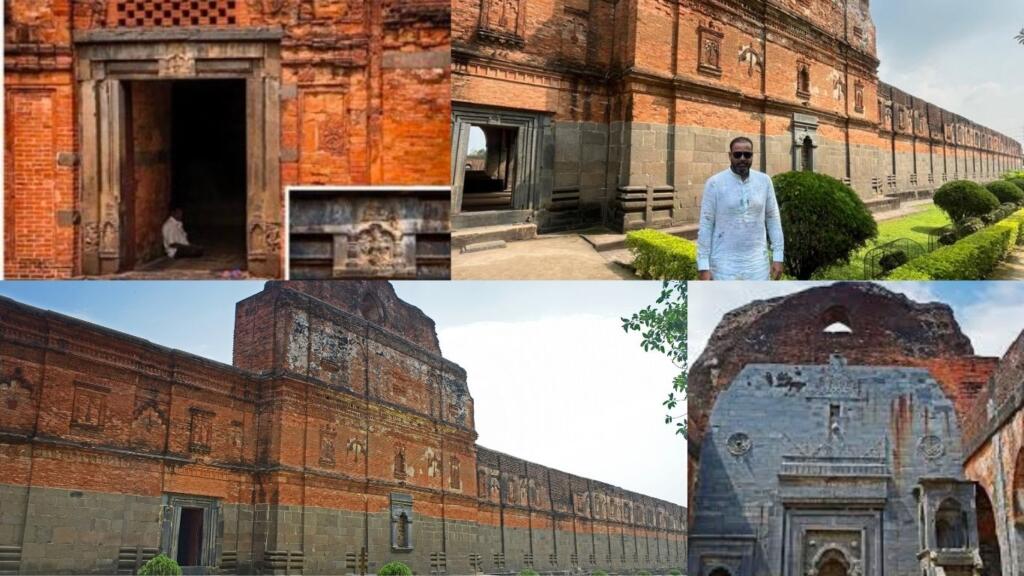

The centuries-old Adina Mosque in Malda, West Bengal, once considered a relic of Islamic architecture, is back in the spotlight this time not for its historical splendour, but for what lies beneath it. The controversy reignited after former cricketer Yusuf Pathan posted on X (formerly Twitter) about his visit to the Adina Mosque on October 16, 2025, describing it as one of Bengal’s architectural jewels. The post immediately triggered a storm online, with users accusing him of ignoring the site’s Hindu origins. “Dear Yusuf Pathan, you are standing in the campus of one of the largest Hindu Temples, Adinath Temple, which was desecrated and occupied by Islamic invaders,” wrote one user, attaching photographs showing motifs and carvings resembling Hindu deities within the monument.

The issue has now turned political, reviving long-standing claims that the so-called mosque is in fact built over a destroyed Hindu temple, the Adinath Mandir. Several historians, priests, and activists assert that Sultan Sikandar Shah of the Ilyas Shahi dynasty demolished a grand Hindu temple in 1373–74 CE and used its remnants to construct the Adina Mosque then touted as the largest mosque in the Indian subcontinent.

From a Temple to a Mosque: A Timeline of Desecration

According to historical accounts, Sultan Sikandar Shah ruled Bengal between 1363 and 1374 CE. He commissioned the Adina Mosque shortly before his death, and the structure became an imperial symbol of the Bengal Sultanate’s might. Yet, many archaeologists and local historians argue that the mosque was constructed using ruins from pre-existing Hindu and Buddhist shrines.

The earliest evidence of this claim comes from visible architectural remnants inside the complex. The mosque’s base is built with heavy basalt masonry, typical of early Hindu temples, while the upper portions employ Islamic brickwork. Several stone slabs feature floral motifs, lotus patterns, and sculpted deities distinctly non-Islamic in design. Locals also refer to the site as “Adinath Dham,” suggesting that the word “Adina” evolved from “Adinath,” one of Lord Shiva’s epithets.

The controversy first erupted in May 2022, when BJP leader Rathindra Bose posted on X that an ancient Adinath Mandir lies buried beneath the mosque structure. “The Adinath Temple sleeps under this Adina Masjid. Jitu Sardar gave his life to save this temple. That history is unknown to many,” he wrote. His post marked the beginning of renewed interest in the site’s origins.

In February 2024, the dispute escalated dramatically when a Hindu priest, Hiranmoy Goswami, led a group of devotees to perform puja inside the ASI-listed Adina Mosque complex. Goswami claimed to have discovered a Shivling and other sacred symbols during his visit. However, the police intervened, citing restrictions under the ASI’s rules for protected monuments, and an FIR was registered against the priest. Videos of the confrontation went viral, showing Goswami arguing with the officers who stopped him. “On what ground are we being restricted from praying here?” he asked, as officers cited his “crime” as offering “pranam wherever he wished.”

Legal Battle and Renewed Demands for Worship Rights

A few weeks after the incident, senior advocate Hari Shankar Jain, known for his role in several temple restoration litigations including the Gyanvapi and Krishna Janmabhoomi cases, took up the Adina dispute. In March 2024, Jain announced that he had written to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah, seeking permission for Hindus to perform puja at the disputed site.

“This so-called mosque was built by demolishing a grand Hindu temple. Many of its symbols are still present. There are thirty-two photographs that clearly show that this was a grand temple and that it was demolished,” Jain stated in a video message posted on X. He cited Section 16 of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, which stipulates that monuments should ideally retain their original religious character in usage.

Jain’s letter reignited the larger debate over historical reclamation, with several right-wing groups asserting that Adina Mosque, like Gyanvapi and Krishna Janmabhoomi, symbolizes centuries of religious subjugation. The call to allow Hindu worship there gained traction across social media platforms, with hashtags such as #AdinathMandir and #ReclaimAdina trending for days.

Meanwhile, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) maintained that the Adina Mosque remains a monument of national importance and is protected under heritage preservation laws. However, critics argue that ASI’s neutral stance effectively sidelines Hindu claims of heritage justice. The ASI’s own documentation acknowledges that the mosque incorporates reused materials from earlier temples, though it avoids explicitly naming them.

Architectural Clues and Historical Evidence: Layers of Truth

Archaeological evidence forms the core of the ongoing argument. Scholars and independent researchers point out several design inconsistencies within the mosque that cannot be attributed to Islamic architecture alone.

Firstly, the mihrab (prayer niche) and arch structures show patterns typical of temple doorways rather than mosque carvings. The pillars and wall reliefs carry iconography such as lotus blooms, concentric mandalas, and dancing human forms. In some corners of the structure, partial depictions of deities, including what resembles Lord Ganesha and Shiva in Nataraja posture, have been reported.

Secondly, the orientation of the structure also raises questions. While mosques traditionally face west (toward Mecca), the core of the Adina structure appears to align with an older east-facing sanctum consistent with Hindu temple architecture.

Finally, local oral traditions and community records strengthen the claim that Adina was once a temple. For generations, villagers in Malda have referred to the site as “Adinath Dham,” conducting occasional rituals in its vicinity long before the ASI took over maintenance. These traditions, say locals, predate British records of the site as a mosque.

Adding to the mystery, regional chronicles suggest that Bengal’s Sultanate rulers frequently repurposed temple ruins for new constructions. The pattern is well documented in sites such as Pandua, Gauda, and Gaur, where temple stones and sculptures were reused in mosque and palace foundations.

Yusuf Pathan’s post inadvertently gave the movement renewed visibility. What began as a simple tourist post has now revived one of Bengal’s oldest and most sensitive debates a question that challenges the state’s historical identity and the boundaries of religious coexistence.

The Call for Truth and Heritage Justice

The Adina Mosque dispute is no longer just a regional controversy it reflects India’s larger struggle to reconcile its layered history. The claims of Hindu origins are not merely faith-based; they rest on visible evidence, architectural logic, and local memory. Whether it was once the grand Adinath Mandir or not, the demand for an impartial archaeological survey is now stronger than ever.

The issue underscores a growing national sentiment that history must be told honestly, not selectively. If the mosque indeed stands upon the ruins of a temple, it represents not just the story of desecration, but also the endurance of a civilization that refuses to forget its roots.

As calls grow louder for a re-examination of sites like Adina, Kashi, and Mathura, one thing is clear: India’s quest for historical truth has only just begun.