Much has been written, read, heard, and seen about the horrors of the India–Pakistan Partition. Most people are familiar with its small, scattered stories… because when eminent writers document it, they tend to keep the “scales balanced.” In doing so, they often assign equal responsibility to both Hindus and Muslims. But the question arises—were Hindus and Muslims really equally responsible?

If you’ve been following prominent journalists, thinkers, and other mixed-leaning intellectuals, you might surely believe that Hindus and Muslims were equally at fault. But the tragic Partition has many such chapters that, if you hear them, will leave you shocked. I am writing this article today with full responsibility to state that the responsibility was not equal. Yes, I stand firm on this point and have many arguments and pieces of evidence to support it.

Why do responsible citizens like you forget to ask: which community was the first to decide to separate from India? It’s quite clear, yet people avoid directly blaming Jinnah. Fine, let’s spare him for a moment. But the fact remains—no Hindu ever demanded a separate Hindu nation before this. The truth is that only one… and a large section of Muslims demanded Partition and the creation of Pakistan, and they were willing to go to any lengths for it.

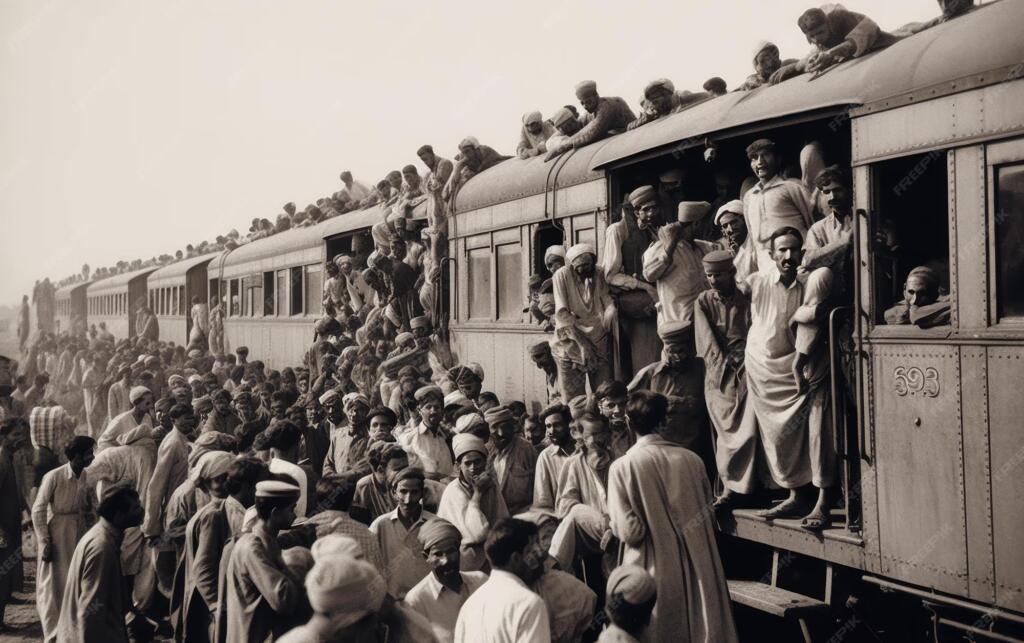

While writing about the tragic India–Pakistan Partition of 1947, my hands tremble, because I have read things that compel me to call the Hindus of that time “the helpless ones.” A question lingers in my mind, which I want to share with you all—do you have any valid answer to this: when Muslims who wanted to go to Pakistan migrated there during Partition, they left voluntarily, but Hindus were forced to leave Pakistan. They were looted, killed, their lands seized, and they were annihilated.

Hindu refugees who came from Pakistan to India were called Indians, but what were the Muslims who left India for Pakistan called? They lived comfortably there. Let me share a truth that will surely shock you—almost no Muslim who left India for Pakistan suffered any loss of land, because when they left, they handed over their property to their relatives here, effectively making them custodians. You must have read in the newspapers about the property dispute of the Pataudi family—that is merely one outcome of Partition’s legacy. Let me explain in detail.

The Partition of 1947 is the deepest wound in Indian history. That year, when the British left, they didn’t just divide a territory; they shook the very foundations of millions of lives. In Punjab, Sindh, and the North-West Frontier Province, prosperous Hindu and Sikh families—whose identities were rooted not just in their wealth but also in their culture, traditions, and generations-old religious sites—were uprooted in an instant.

They left behind: over 4 million acres of fertile agricultural land, thousands of mansions, countless shops, hundreds of major industrial establishments, crores of rupees in bank deposits, and a rich cultural and religious heritage built over generations. In West Punjab alone, Hindus and Sikhs jointly owned several lakh acres of land. In Sindh, despite being only 15% of the population, they owned 72% of urban property and trade. All of this was permanently lost with the creation of Pakistan.

Pakistan immediately declared these properties as “Evacuee Property,” took them under state control, and in 1960 handed them to an institution called the Evacuee Trust Property Board. Even today, this board controls over 109,000 acres of land and more than 15,000 buildings in Pakistan. In Punjab province alone, 85,000 acres are rented out, generating around ₹35 crore annually in 2018–19. This property was once the hard-earned wealth of Hindus and Sikhs—but now, neither they nor their descendants are allowed to access or benefit from it.

Before Partition, the 1941 Census showed Hindus made up about 29% of West Punjab and Sikhs about 15%. By 1951, these numbers dropped to nearly zero. The Sikh community, 6% of Pakistan’s population in 1941, was almost entirely forced to settle in India after Partition. This migration not only erased their social presence but also uprooted their economic base.

In contrast, India enacted the Evacuee Property Act, 1950 for Muslims who migrated to Pakistan, which allowed their relatives in India to use the property with the custodian’s permission. This provision legally protected the property of Muslims who left for Pakistan. Many Muslim families continued to benefit from their houses, farms, and shops in India even after settling in Pakistan—through their relatives here.

India created the Displaced Persons (Claims) Act, 1950 and the Displaced Persons (Compensation and Rehabilitation) Act, 1954 for rehabilitating Hindu and Sikh refugees from Pakistan. The compensation pool included Muslim properties left in India. Refugees received cash, government bonds, houses or shops in urban areas, and agricultural land in rural areas. Under the “Quasi-Permanent Allotment” scheme in Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan, about 26 lakh acres of land were distributed; in Delhi and other cities, over 1 lakh urban properties were allotted; and the Displaced Persons (Debt Adjustment) Act, 1951 relieved thousands of families from old debts.

Yet, this compensation could never match the actual losses. Someone who left behind a multi-crore haveli in central Lahore got an ordinary house in an Indian town. Someone who abandoned thousands of acres of irrigated land in Sindh was given barren desert land in Rajasthan. The official “certified claim” value used for compensation was far below the real market value.

The example of the Mahmoodabad Estate shows how property of those who migrated to Pakistan could remain under Indian custodian control for decades, with legal battles still possible and even verdicts in favour of heirs—although later amendments curtailed such rights. Similarly, the Bhopal–Pataudi property dispute shows that Muslim family properties in India could survive long legal processes, while in Pakistan the rights of Hindus and Sikhs were instantly and permanently erased.

The allocation of Muslim evacuee land in Punjab was a relief for refugees, but often this land was less fertile and less valuable than what they had lost. India tried to rehabilitate them, but Pakistan simply distributed Hindu–Sikh land and properties among its own citizens—without compensation or alternatives for the original owners.

The 1950 Nehru–Liaquat Pact, in which both nations guaranteed protection of minorities and their property rights, was implemented in India through laws and the custodian system. Pakistan, however, never honoured this promise. Its government not only deprived Hindus and Sikhs of their property but also took control of their religious sites and cultural symbols.

Even today, there are people in India who support Pakistan’s stance, defend its policies, and ignore this historical injustice. They must understand that a Pakistani Muslim can still benefit from property left in India through relatives, but a Pakistani Hindu cannot even step onto the threshold of his former home. His property is locked by the government, and his religious identity has been erased.

This is not just history—it is ongoing proof of inequality. This entire perspective warns us that a nation built on a religious basis never truly gives justice and equality to its minorities. Pakistan is a living example of this. In Partition, the real sacrifice and loss were borne by the Hindu and Sikh communities. They lost not only economically, but also culturally and emotionally. Their pain is not just a part of history—it is part of our national memory, which must be preserved and passed on to future generations, so they know the price at which today’s India stands.

This article has been written for us by Dr. Raghvendra Pratap Singh, Post-Doctoral Fellow at the University of Allahabad. He is a political analyst specializing in governance, geopolitics, and electoral studies.

To read this piece in hindi, click here.