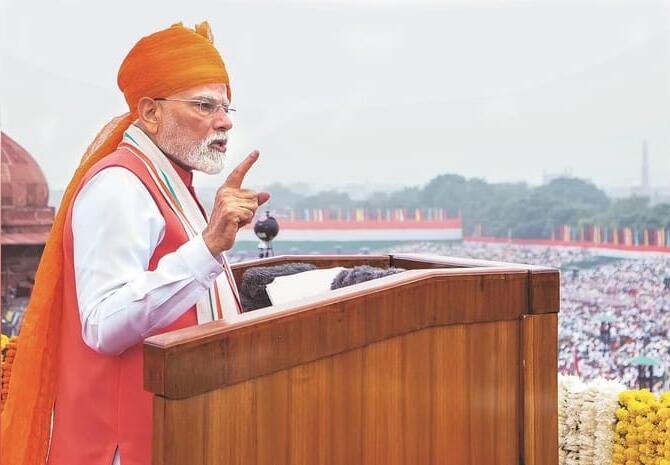

On the 79th Independence Day of India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivered a speech that carried both inspiration and recognition. In this address, he did something no Prime Minister of the country had done before—he openly praised the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) for its contribution to the nation. His words highlighted the unique and selfless role played by the organisation in building India’s social and cultural fabric.

Prime Minister Modi emphasised that the RSS has worked tirelessly for the welfare, unity, and progress of the nation. He noted that the organisation has grown because of its values of discipline, dedication, and service. With these qualities at its core, the RSS has flourished to become one of the largest voluntary organisations in the world. According to him, it is this spirit of service and commitment to the country that sets the RSS apart.

When the Prime Minister of India offers such praise, it is not merely a passing comment. It invites the people of India, especially the youth, to reflect more deeply on the role of such organisations in nation-building. It urges us to look at history and understand how the RSS, founded in 1925 by Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar in Nagpur, has endured for a century—shaping society, inspiring volunteers, and contributing to national life in countless ways.

The Prime Minister’s words also encourage reflection and debate. The RSS has often been misunderstood and criticised, yet its impact on civil society, politics, culture, and community service is undeniable. From relief work during natural disasters to spreading education and health awareness, the organisation has built a wide network touching millions of lives.

Core Values of the RSS

The RSS was conceived at a time when India’s freedom struggle was gaining momentum. Dr. Hedgewar, a freedom fighter himself, believed that colonial subjugation was not just political but also cultural and social. It stemmed from disunity, lack of discipline, and neglect of civic duties. Thus, the goal was to cultivate civic awareness and social responsibility among citizens, especially the youth. He envisioned an organisation that would revive India’s civilisational pride while instilling discipline, character, and patriotism.

From a handful of swayamsevaks (volunteers) in Nagpur, the RSS expanded to thousands of shakhas across India, surviving bans, political repression, and ideological opposition. Today, it claims to be the world’s largest voluntary socio-cultural organisation, with millions of swayamsevaks participating daily. The innovative shakha system has moulded young volunteers for leadership in social service, education, politics, and professional life. Many RSS-trained individuals have gone on to become administrators, scientists, soldiers, teachers, and political leaders.

One of the RSS’s most significant contributions has been fostering a strong spirit of volunteerism. Over the years, swayamsevaks have stepped forward in times of need—whether during war, communal tensions, natural calamities, or global health emergencies. For example, during the Partition in 1947, volunteers protected refugees and offered humanitarian support. Similarly, during the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, the 2018 Kerala floods, and the COVID-19 pandemic, RSS cadres, through organisations like Seva Bharati, distributed food, set up relief camps, organised medical aid, and provided emotional support.

Beyond emergency relief, the RSS has worked continuously at the grassroots level in education, healthcare, and rural development. Affiliate organisations—collectively called the Sangh Parivar—have been active in this work. Vidya Bharati runs thousands of schools focusing on both academics and cultural awareness. Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram is devoted to the welfare of tribal communities, while Bharatiya Shikshan Mandal promotes educational reforms to connect students with India’s roots while preparing them for modern challenges. Many of these schools serve children from economically weaker sections, bridging gaps left by mainstream education.

The organisation also promotes Indian languages, traditional arts, and knowledge systems. Activities include community festival celebrations, Sanskrit classes, folk art preservation, and encouraging yoga and Ayurveda. The aim is to preserve India’s plural and diverse cultural heritage in a globalising world.

Although the RSS defines itself as socio-cultural, its influence on politics is unmistakable. It nurtured the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, which evolved into today’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Themes such as swadeshi, cow protection, and cultural nationalism have shaped public policy. Its disciplined, cadre-based approach to politics has left a lasting mark on campaign styles in India.

Critics, however, accuse the RSS of promoting a majoritarian worldview. They argue that its idea of Hindutva gives greater importance to Hindu traditions, potentially side-lining other religions and cultures. Some affiliated groups have been accused of spreading polarisation. The RSS’s early opposition to certain parts of the Constitution, especially its secular principles, has also drawn scrutiny. Critics further note its limited space for women’s participation.

The RSS maintains that its ultimate aim is social harmony. It has worked for the upliftment of marginalised communities through inter-caste dining, campaigns against untouchability, and efforts to integrate neglected groups into the mainstream.

Thus, while opinions differ, the RSS’s impact on Indian society is undeniable. Its volunteer network, grassroots development work, cultural preservation, and political influence have left a lasting imprint on modern India.

The centenary of the RSS is an opportunity to look back and look ahead. For India’s youth, the Prime Minister’s speech is a message to understand, question, and learn from such organisations. The lesson is that critical engagement—rather than blind acceptance or outright rejection—builds maturity and balance. The RSS itself encourages dialogue on seva (service), sangathan (organisation), and samajik samrasta (social harmony). These must be reinterpreted by each generation to find creative ways of building a stronger, more harmonious, and progressive India.

This piece is written by Prof Vivek Misra, Dean of School of Social Sciences, Rani Durgawati University, Jabalpur.