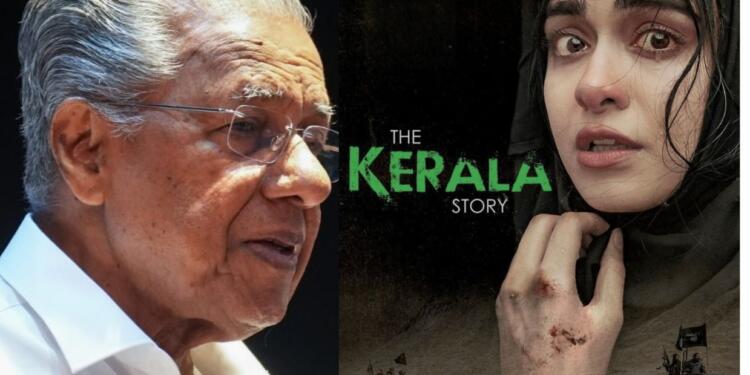

The decision to confer two National Film Awards on The Kerala Story for Best Director and Best Cinematography has ignited a sharp political backlash in Kerala, with Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan and opposition congress leaders denouncing the film as a politically motivated attack on the state’s image.

Directed by Sudipto Sen and starring Adah Sharma, the 2023 drama narrates the fictionalized account of three women from Kerala allegedly lured into religious conversion and recruited by ISIS. The film’s portrayal has drawn criticism from sections of Kerala’s political and cultural leadership, who see it as misrepresenting the state’s ethos of communal harmony.

Kerala CM Terms Award a ‘Grave Insult’

Reacting to the awards, CM Vijayan called the jury’s recognition ‘a grave insult’ to Kerala. In a post on X, he said the film spreads ‘blatant misinformation’ and accused it of being rooted in ‘the divisive ideology of the Sangh Parivar.’ He further described the film as an affront to the tradition of Indian cinema, which, he argued, has historically promoted unity and national integration.

‘Kerala, a land that has always stood as a beacon of harmony and resistance against communal forces, has been gravely insulted by this decision,’ he stated.

Opposition Congress leader V. D. Satheesan echoed the Chief Minister’s concerns, asserting that the film ‘spreads religious hatred’ and is part of a political project aimed at gaining advantage by vilifying Kerala.

Controversy Over Content and Claims

Much of the outrage revolves around the film’s claim that 32,000 women from Kerala were converted and recruited by ISIS, an assertion widely discredited by investigative reports and government data. Many Malayalis, particularly from left-leaning and liberal circles, view the film as an oversimplification of sensitive issues, warning that it could deepen communal divisions by stereotyping Kerala’s Muslim population.

Described by its critics as ‘propaganda’ and ‘no-nuance filmmaking,’ the film has nonetheless resonated with national audiences and enjoyed commercial success, pointing to a broader appetite for content that addresses issues of internal security and radicalization.

Cinema’s Role in National Discourse

Supporters of The Kerala Story argue that the film, while dramatized, raises uncomfortable but necessary questions about the grooming and exploitation of women, the lure of extremist ideologies, and the vulnerability of youth across the country, not just in Kerala.

In that light, the film is seen by some commentators as contributing to national dialogue on security and indoctrination, even if its storytelling methods or numbers are disputed. Many Political Commentators note that cinema is inherently political, and when films align with government concerns such as national security, they tend to generate deeper engagement.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi had earlier endorsed the film in public speeches, stating it exposed ‘ugly truths’ that needed attention, suggesting a view of cinema not just as entertainment, but as a vehicle for national awareness.

Artistic Recognition vs. Political Rejection

At the heart of the debate is a larger question: should recognition at a national platform be withheld from a film because it challenges or unsettles local political narratives?

The National Film Awards have historically honoured films that pushed boundaries on caste, gender, corruption, and conflict, many of which offended prevailing sensibilities at the time. Does the backlash against The Kerala Story reflect a discomfort with its content, or a broader tension between political authority and artistic freedom?

It is worth asking: should political leaders attempt to define what constitutes acceptable cinema? Can art serve national interest without being labelled propaganda? And does honouring a film necessarily mean endorsing every aspect of its message?

A Space for Difficult Conversations

While The Kerala Story remains a polarizing work, its national recognition has placed it firmly in the realm of public discourse. For its supporters, the film’s value lies not just in its technical execution, but in its willingness to address radicalization, a subject often tiptoed around in mainstream storytelling.

In a democracy, does cinema not deserve the freedom to provoke, even if it unsettles? And in rejecting the jury’s decision, is there a risk that political outrage may inadvertently narrow the space for cinematic dissent and artistic exploration?

These questions remain open at the intersection of politics, art, and the ever-evolving idea of Bharat.