As Bihar braces for its upcoming Assembly elections in October-November this year, a quiet but powerful storm is brewing behind the scenes- one that could shape not just the electoral landscape, but also public trust in the process itself.

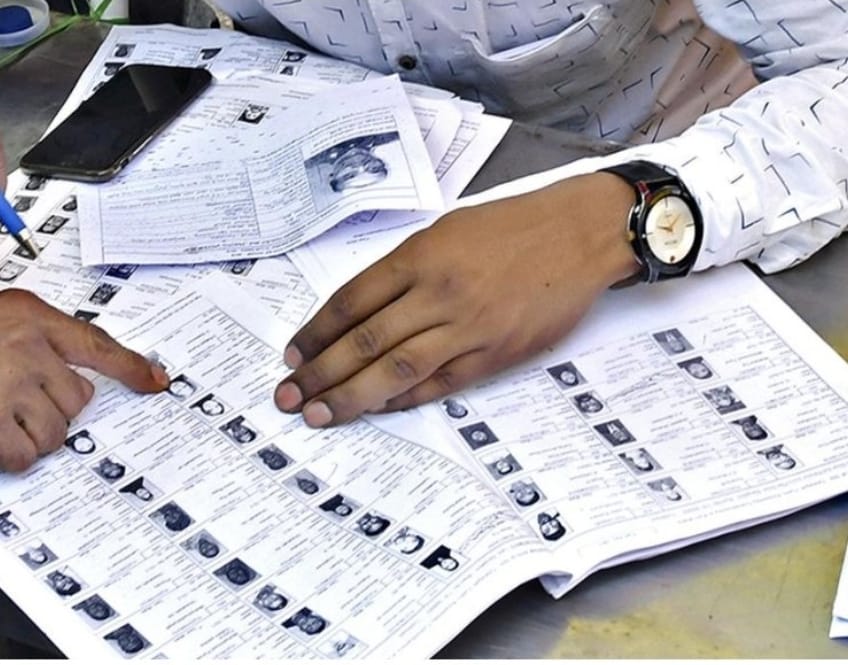

Over the past few weeks, the Election Commission of India (ECI) has launched a door-to-door verification drive under its Special Intensive Revision (SIR) program, which began on June 24. What was meant to be a routine check to update and clean the voter rolls has taken a dramatic turn.

Allegations of Foreign Nationals on Voter Rolls

According to sources within the Election Commission and as reported by media; field-level officers have flagged an alarmingly ‘large number’ of individuals from Nepal, Bangladesh, and Myanmar who are currently living in Bihar and appear to have obtained Indian voter documents through dubious means.

These individuals were reportedly found to be in possession of Aadhaar cards, domicile certificates, and ration cards, raising questions about how such critical identity documents were acquired, and how many of them might already be on the voter list.

The verification drive is now focused on identifying and investigating these cases between August 1 and August 30. The final electoral roll will be published on September 30, and any names found to be ineligible will be struck off after proper inquiry, ECI officials have confirmed.

But this exercise is already having wide-ranging political and legal ramifications.

Tensions Soar

The ruling BJP has backed the Commission’s efforts, framing the drive as a necessary move to weed out fake or illegal voters, especially in light of recent national crackdowns on illegal migrants in states like Assam and West Bengal.

However, the Opposition sees a very different story.

Leaders from the RJD and Congress have alleged that the timing of this verification, so close to state elections, is deeply suspect. They warn it could be used as a tool to disenfranchise legitimate voters, especially among the minority and migrant working-class populations.

Speaking at a press conference in Patna, Congress leader Abhishek Manu Singhvi called the move ‘dangerous and bizarre,’ accusing the EC of adopting an ‘arbitrary and legally questionable’ stance. He was particularly critical of the idea, reportedly floated by some ECI officials, of treating all voters added after 2003 as ‘suspect’ unless proven otherwise.

In fact, Congress and RJD leaders have gone so far as to accuse the government of using the voter list revision as a form of voter suppression, targeting communities that traditionally don’t support the ruling party.

Supreme Court Steps In

Given the controversy, the matter has already reached the Supreme Court of India, which heard petitions earlier this month questioning the legality and timing of the ECI’s actions.

During the hearing, the bench expressed ‘serious doubts’ about whether the Commission could complete this massive task without wrongly disenfranchising genuine Indian citizens. The Court emphasized that voter ID cards, Aadhaar, and ration cards should be accepted as legitimate documents- a point of contention, given the reports that some of these very documents were obtained fraudulently.

The Court also remarked that such a sweeping verification effort should ideally be decoupled from election timelines to avoid politicization and ensure due process.

Ground-Level Realities

On the ground, the picture is more complex than any political narrative can capture.

In border areas and urban slums across Bihar, migration is a way of life. Families from Nepal, Bangladesh, and even Myanmar have lived in these regions for decades. Many came seeking work, fleeing conflict, or escaping economic hardship. Over time, many have integrated into local communities, making the line between legal and illegal, or citizen and migrant, increasingly blurry.

Some of these individuals claim to have valid Aadhaar and ration cards issued years ago. ‘No one ever told us we weren’t citizens,’ says Salma Begum, a resident of Purnea, whose family migrated from Bangladesh in the 1990s. ‘Now they’re saying we’re illegal voters. How?’

Meanwhile, Booth Level Officers (BLOs), the foot soldiers of the election machinery face the uphill task of distinguishing between genuine documentation and forged identity. In areas like Sitamarhi, Kishanganj, and Araria, the blurring of borders, identities, and bureaucratic loopholes has created the perfect storm.

What Next?

As the revision drive continues through August, all eyes are on two key outcomes:

How many names will ultimately be removed from the voter list, and on what grounds?

How will this affect the outcome of the election, especially in constituencies with significant migrant or minority populations?

The final roll, due September 30, will likely be the most scrutinized voter list Bihar has seen in decades.

This exercise could be remembered either as a bold attempt to clean the electoral rolls and uphold the sanctity of voting, or as a mismanaged purge that disenfranchised the poor, voiceless, and politically inconvenient.

One thing is certain: this is no longer just about voter ID cards. It’s about the future of democratic participation in one of India’s most politically charged states, and the price of being counted.