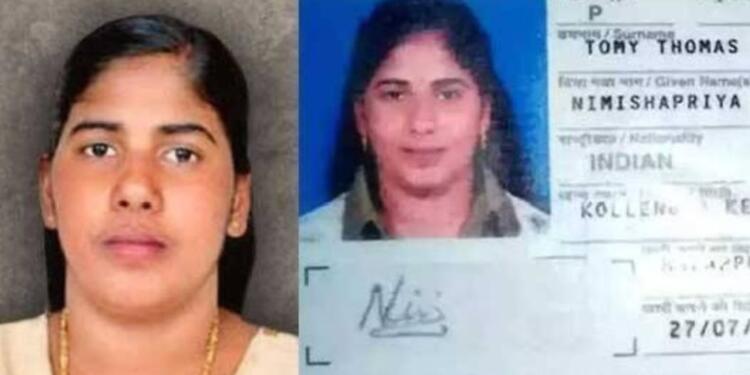

The countdown has started for Indian nurse Nimisha Priya, a 37-year-old mother from Kerala’s Palakkad district, who now faces execution in Yemen on July 16. Her crime? Killing a man who, according to her family and advocates, subjected her to months of relentless physical, sexual, and financial abuse. What began as a desperate bid for survival has now escalated into a global call for justice; and a test of India’s will to protect its citizens abroad.

Tomy Thomas, her husband, says the family has received no official communication about the execution date but it was confirmed by Samuel Jerome Baskaran, a social worker and negotiator leading talks with the family of Talal Abdo Mehdi, the victim in the case. ‘The public prosecutor has issued the letter of execution to the jail authorities. The execution is scheduled for July 16,’ said Baskaran. ‘However, options are still open. The Indian government can intervene decisively to save her life.’

From Nurse to Survivor in a Foreign Land

Born into a family of daily-wage labourers, Nimisha worked her way up to become a nurse and moved to Yemen in 2008 in search of a better life. She married and had a daughter with Tomy Thomas. By 2014, she dreamed of independence and decided to open a clinic in Sana’a; a move that would place her in a deadly partnership with Talal Abdo Mahdi, a Yemeni national she was required to include as a co-owner under local law.

What followed, according to her family, was a nightmare. Mahdi allegedly abused her, stole her income, seized her travel documents, and forged documents claiming she was his wife. When she complained to authorities, he retaliated with harassment and physical assault.

Desperate to escape, Nimisha tried to retrieve her passport by injecting Mahdi with sedatives, not to kill him, but to flee the abuse. The sedatives proved fatal. In sheer panic, and aided by another nurse, she dismembered his body to hide the death. The two went into hiding but were soon arrested. What followed was a harsh trial with minimal oversight, and in 2020, Nimisha was sentenced to death.

Conviction Without Context: A Grave Miscarriage of Justice

Nimisha’s story is not one of cold-blooded murder. It is the story of a woman pushed to the edge in a foreign land, without legal protections, and trapped by an abusive man who stripped her of dignity and freedom. This is not just a criminal case, but a human rights crisis.

In many countries, women in similar situations are offered protection, or at the very least, their trauma is considered a mitigating factor. In Nimisha’s case, there has been no such compassion. Instead, she was prosecuted under a legal regime in rebel-held northern Yemen; a region where even the United Nations-recognised Yemeni government disavows the judicial process, stating the execution order was never ratified by the official president.

India has no diplomatic presence in Sana’a, which is under the control of the Iran-backed Houthi rebels, further isolating Nimisha and complicating rescue efforts. The result? An Indian citizen may be executed under a quasi-legal framework, without full international oversight or due process- a dangerous precedent.

Blood Money, Bureaucracy, and a Race Against Time

In Islamic law, a convicted murderer may be spared through ‘diya’- blood money paid to the victim’s family. Nimisha’s supporters, including the Save Nimisha Priya International Action Council, have offered up to $1 million (₹8.5 crore). Baskaran, who has returned to Yemen to resume talks, says, ‘We had made an offer to the family. So far, they have not responded. But we are still trying’.

Despite a seemingly indifferent system, Nimisha’s mother Prema Kumari, a domestic worker from Kochi has remained in Sana’a for over a year, making direct appeals to save her daughter. She has risked everything- her safety, her livelihood, to stop her daughter from being executed.

The Indian Government Must Do More

The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) says it is extending all possible assistance. But for Nimisha’s family and countless supporters, time and statements are no longer enough. What’s needed now is high-level diplomatic intervention. If India cannot protect its vulnerable citizens abroad, especially women, who will?

Nimisha is not just a convict. She is a survivor, a mother, and a symbol of systemic failure. Her death will not be justice, it will be a stain.

With barely a week left, the campaign to save Nimisha has entered its most critical phase. A mother’s hope, a negotiator’s mission, and a nation’s diplomatic resolve now converge in a race against time.